February was Black History month. High school walls were plastered with static pictures of Martin Luther King Jr. and Harriet Tubman. All were reminded of the popular, pervasive, skeletal chronology of America’s Black history: slavery, Civil Rights, Obama. What happens when the public memorial of eminent Black figures in US history begins to cast a shadow on the people it intended to represent? Our collective memory seems to be like seasoned and slowly simmered pot liquor—potent, satisfying and familiar. But now, in the days of pre-packaged, done-in-3-minutes, ready-to-serve everything, who remembers what actually goes into the pot? Who was King leading? Barbers, aspiring artists, 17-year-old boys who weren’t sure what exactly they wanted to do with their lives? The erecting of huge, flat, figurative cultural monuments, though undeniably well-deserved, has created a dark, shadowy area where the rest of Black history lies— relatively untouched and unmentioned even and especially during Black History month.

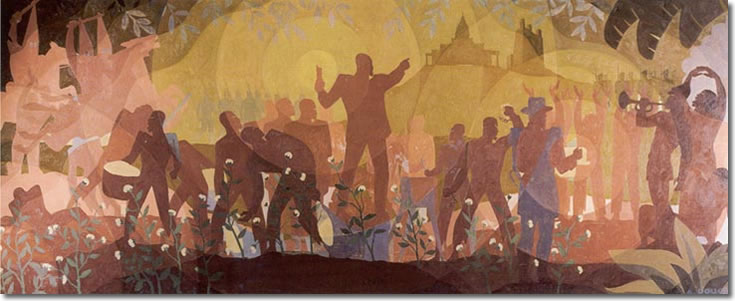

Perhaps the overuse of the same people, places and events leaves us disinterested in learning more. There is a corresponding Black history buzzword for every conceivable arena; “Black Arts” is to the Harlem Renaissance as “Rosa Parks” is to Civil Rights boycotts. Today, we are asked to see Black history as a broad, sweeping, national trajectory over time with geographically and temporally disconnected milestones as guides.

I do not wish to trivialize or minimize the extraordinary contributions that canonized Black figures and movements have made to an incredible African American legacy. However, I believe that an alternative method to truly exploring Black History will prove to be refreshing, more comprehensive and generally beneficial for those invested. Chicago, the third largest city in the US, serves as an incredible alternative site for re-situating Black history in the United States. With ethnographic, sociological and historical works like Drake and Cayton’s Black Metropolis: A Study of Negro Life in a Northern City (1945), we are able to get concrete facts about the individuals living at a time that is generally characterized as “after the Civil War” to any pedestrian privy to the prevalent Black history continuum previously described. Newspaper clippings and short interviews alongside maps and tables allow for an individualization of Blacks as a part of the American story that we are rarely afforded; an individualization that is essential to recovering a vibrant and real past.

Side-by-side, then and now, analysis has emphasized difference and change and disallowed for the recognition of sameness. That sameness is the thread of humanity that allows those living now to even imagine “then” as being a time and place inhabited by real life people—doing, saying, eating writing, singing, loving etc. Black Metropolis, sixty-five years after its first publication, highlights both the difference and the similarity. It is a book about the people. It recognizes a Black History that was and continues to be. Of course, the book is not without its faults and, thankfully, scholarship has come a great way since then. However, the point remains that America’s Black history is as much a history of leaders and pronounced figures as it is a history of Sunday dinners and personal stories. All parts are equally important and should be remembered as such.

JS

Tags: Black Arts, Black History Month, Black Metropolis, Harlem Renaissance, Horace Cayton, Martin Luther King, Obama, Rosa Parks, St. Clair Drake

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It