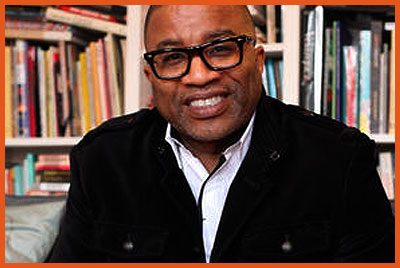

To watch V. Shayne Frederick—who stars in the recently released debut of Dr. Guy’s Office Hours video series and has his own new album, Lovesome, out now—perform feels like observing one of the old, early-twentieth-century masters’ energies and vocal stylings transposed into a contemporary form. His rich timbral tone vibrates your sternum when it hits the right notes (it never fails to), stretching across his wide register and rich palette. His repertoire is vast but curated, reaching deep into the jazz songbook for forgotten songs that he makes feel like standards. He’s an artist’s artist, in part because it seems almost effortless—like he’s never been anything but.

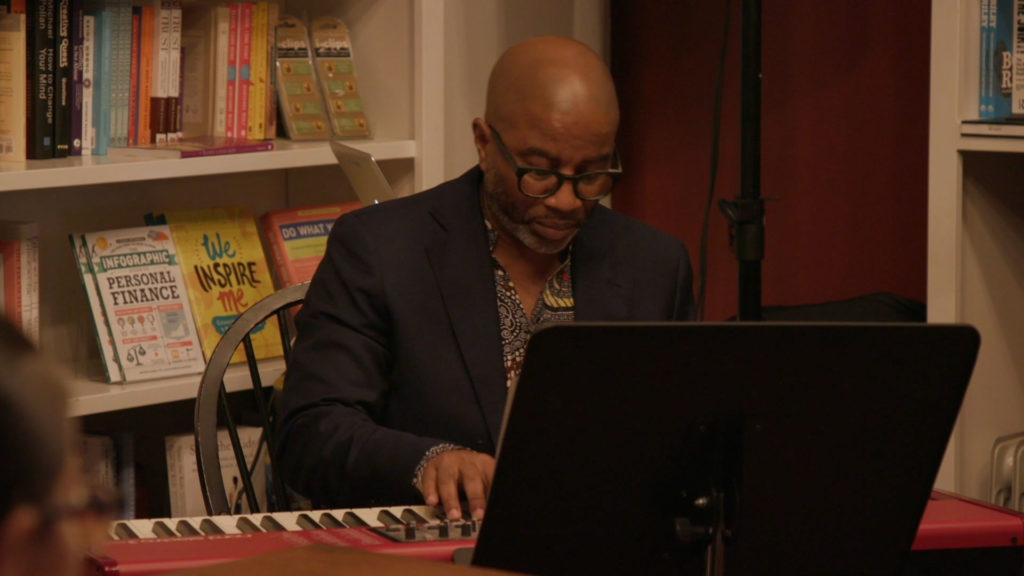

Case in point: It’s the inaugural session for Dr. Guy’s Office Hours, a new concept inspired by the intimate NPR Tiny Desk video series. The tune is “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free,” a 1952 composition by Dr. Billy Taylor, the pianist and composer, coming alongside 1920s Jazz Age tunes and Negro Spirituals. Popularized by Nina Simone, whose determined version was one of her iconic recordings, the listening experience is buoyed as the song’s affirmative message unspools. In Frederick’s hands and voice, the audience hangs on every melismatic syllable, every flourish of his arms, every timbral shift from growl to whisper, and every play-acted surprised eye-opening at the sound his body has just made. To take in Frederick in performance is to behold an artist at work.

But Frederick—who would seem to have emerged well-coiffed and of a certain artistic sensibility—admits music was not always a pursuit grounded in aesthetics and elegance for him. In fact, the North Carolina-born child of musicians suggests that in his early life, music was more quotidian, a necessary communicative and familial practice than art for art’s sake. “My parents never gave me lessons in any didactic way,” he says. “I just watched, listened, and experienced being in musical culture and musical appreciation culture.”

It was only after moving to Philadelphia during his college “extra-curriculars”—at Ortlieb’s JazzHaus and long-shuttered piano bars’ gigs—where he began to cut his teeth and establish a foothold in a city that for all its hard edges does nurture young artists as they climb the ranks. It’s hard to imagine Frederick—who now has twice-weekly residencies at South Jazz Kitchen on Broad and Eddie V’s in King of Prussia—as a neophyte player, but he admits it took time and work, both on his own practice and the city’s scene more broadly. “It took a while to get the respect of people around here,” he admits. “It’s not like I popped up one day and was like, ‘Hey, guys, I’m a jazz artist, hire me!’ That’s not how it goes. People have to look at you crazy for ten years before they give you any kind of respect.”

A decade later, he’s found that respect, his voice, and his space with gigs like Office Hours, which was filmed in late 2018 and debuted online earlier this week. Filmed live at Uncle Bobbie’s Coffee & Books, a hub for black literature, events, and knowledge-creation, in Germantown—the show features Frederick, Dr. Guy, drummer Marcus Myers and bassist Nimrod Speaks in a stripped-down, vérité-style performance. “I knew V. Shayne would be the perfect artist to debut this new series because he was such a perfect vessel to help us convey the style, substance, and sound of the program we are trying to establish,” Dr. Guy says. “And the fact that we got to do this alongside his tremendous new release, Lovesome, is a bonus.”

When asked, Frederick cites a pair of questions he asks himself and others that guide his musical approach. The first—“Do I believe you?”—is a barometer he uses in vocal coaching, vital, he says, to help artists tap into a place from which authentic connection to the audience can occur. “If you don’t believe it, you look like you don’t,” he says prophetically. Turning the mirror on himself, the question, when asked, serves as a mission statement of sorts, activating the kind of artmaking process he intends to cultivate.

“Honesty is always a tall order for pop music because pop music is un-intrusive. And the truth intrudes, by the nature of what truth is,” he says. “The truth is gonna break you down, make you uncomfortable, and make us all feel naked. You know…you’ve got someone like Billie Holiday or Carmen McRae or whomever telling their truth, it exposes us all. The truth exposes everybody in the room.”

LISTEN TO LOVESOME ON SPOTIFY.

It’s this kind of historic-contextual sensibility and orientation toward truth-telling that made Frederick an obvious candidate to recruit for the “Hide/Melt/Ghost” performances of the past year, working as a sonorous fuser of temporal states. He cites the feeling of the room changing when the ensemble strikes up “Run Nigger Run,” a macabre carnivalesque experience that marks the tensions the performance invokes.

“This is the art that disturbs the comforted and comforts the disturbed…it’s all of that,” he says of Hide/Melt/Ghost, citing Abbey Lincoln’s preparation to scream during the We Insist! Freedom Now suite as an influence when he reflects on what he sees as H/M/G’s role. “It’s about embracing living in the discomfort. It’s really about finding a way to negotiate your black body into a really uncomfortable space, occupying it, and being a vessel for the music. And being on the microphone for everyone else who doesn’t have the microphone.”

The body is key to the second of his guiding questions: “Where does this all sit in your body?” he asks himself, suggesting that the body can be the key to new, personal innovation, even if the case is a decades-old song. The body—individual, personal—is where new, honest interpretations can be unlocked. “We know what ‘My Funny Valentine’ sounds like,” he jokes. “Now what do you have to say about this song? People pay this to discover what you have to say about the song. Because if we wanted to hear the recording, we could stay at home and do that. But what is your reading of it? And where does it sit in your body? Where does this all sit in your body? Where does it sit in your voice? Where is your tessitura; how can you play with this song? What do you have to say about this piece?”

These questions inform his most noteworthy quality as a vocalist: What sticks out about him on first hearing is his wide vocal range, which allows him to jump from bass growl to warm tenor without sacrificing clarity or tone. Audible gasps are part and parcel of seeing Frederick in concert as audiences are wowed by his versatility and range, a quality he knows could play as a parlor trick but insists is a truly organic happening. “Range is just one of my colors,” he says. Textures, and colors, and again being trying transgressive with some…I use all of that as coloring agents to really demonstrate my interpretation of whatever that piece is. I mean, I’m not just singing 3 or 4 octaves on everything just to be doing it. What I am doing vocally is I’m responding to where the song sits in my body.”

“I think it adds more space and more texture,” he continues. “I think when you’re able to go in different terrains and really explore the limitations to something to the best of your human ability, it allows people to see it in a different way. So I do a lot of mimicry and repetition as a way to explore the songs. It’s all about exploration.”

A multivalent and expansive approach to the idea of “range” is evident on Lovesome, which was recorded over the last year and a half at various studios throughout the city including Rittenhouse Soundworks, Spice House Sound, and Keystone Soundworks. Range here is of vocality but also of sonics. It opens with a sitar before a completely reharmonized take on popular 1919 standard, “The World is Waiting for the Sunrise,” which also appears as part of the Office Hours set. The whole record features these flourishes: a curated collection of covers and reinterpretations that somehow feels completely artistically original.

“There is always space to be taken to delineate in a little bit of freedom around the song form, and it is really to rip something open and stretch it out,” Frederick says of his approach as curator and re-interpreter. “I was taught that good jazz musicians will give a nod to the original and then go off in their own way. So I guess everything I do has a jazz approach to it.”

That jazz approach suits him well, making him stand out among the faces and sounds of a new Philadelphia, a city that has its own rich tradition but is making itself on the fly and feels rife for exploration, with pieces like Office Hours and spaces like Uncle Bobbie’s presenting themselves as opportunities. “The audience is equally as much of a musician in a certain regard receptively, as the performers are,” Frederick says. “And I like to play with that space. That’s where the storytelling happens, for me. I’m always looking for the story.”

V. Shayne Frederick’s Lovesome is available on all streaming services. See him on Tuesdays and Fridays at Eddie V’s in King of Prussia and South Jazz Kitchen on Wednesdays, in addition to other shows posted on his website. Dr. Guy’s Office Hours is a new video series that features local artists in stripped-down community settings.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It