Writer Gay Talese set out to interview Frank Sinatra for Esquire in 1965, during a period in the singer’s career that Billboard was calling “the peak of his eminence.” Dogged by media and tired of publicity, Sinatra refused to sit for an interview with Talese at least in part due to another, seemingly more mundane reason: He had a cold.

The resulting piece “Frank Sinatra Has a Cold,” was a hallmark of a movement that became known as “New Journalism.” Featuring subjective, fictionalistic writing rather than the droll repetition of facts that many expected “journalism” to be, Talese spent days in Sinatra’s Los Angeles orbit, interviewing anyone he could and bringing the writer himself into the picture.

The piece set a new standard, but it also led to the popularization of a surprising tactic in journalistic practice: the write-around.

What do you do when you’re writing about a subject who won’t sit down for an interview? What if you’re assigned 2,000 words and the subject gives you two minutes in between twelve other call-ins and peppers their responses with aphorisms and nothingness? What if your car breaks down on the way to the interview with an artist hopping on a plane to a tour date in Bozeman, Montana immediately after their show ends?

The write-around emerged as a useful tactic for working journalists whose subjects proved unavailable or uninterested. David Letterman in New York. Marlon Brando in Tahiti in The Washington Post. And particularly germane to our interests, the write-around helped John Jeremiah Sullivan sing “The Ballad of Geeshie and Elvie,” on two mysterious black women whose 1930 recordings in a Wisconsin cabin might be the first American blues records.

For what we miss in pithy anecdotes and the newsstand capital-driving glossy celebrity cover photo, the write-around helps readers better understand the subjects in context, a tactic used to great effect in Rembert Browne’s recent piece for Bleacher Report, aptly titled “Colin Kaepernick Has a Job” in an homage to Talese. What do their friends think of them? What do the bartenders in the clubs they fill think? These types of interactions—usually called “secondaries” in journalistic parlance because they took a backseat to the main event—often told you more about your subject than the subject was interested in sharing about themselves.

So what’s not to like? Now that I’ve valorized the write-around, I want to criticize a particular arena where I feel its utility has been over-emphasized at the expense of the voice of the subject. This has led to a model of scholarship where close-reading and scholarly interpretation leaves a wide-open discursive universe (or discursiverse, if you prefer) where our own readings and translations are effectively spoken into truth without giving our subjects the opportunity to affirm or deny the veracity of our claims.

More specifically, what I mean to suggest is that academic writing sometimes feels like one big universe of write-arounds.

This is certainly not true across academe—I have a deep and abiding respect for social scientific field and ethnographic methods, which would find the premise of this article ridiculous. This piece is also not intended to fuel the fire of nonsensical criticism many culture-and-text-oriented scholars often receive from the so-called “harder” sciences.” You know the ones I mean. The ones who’ll look at you straight-facedly and say, “So you just like…listen to songs…and write about them?”

What this is instead is a call to action—a provocation that suggests that the academic knowledge-creation project can and should be about more than our own theories about the hidden meanings behind the lyrics of our favorite artist. Particularly in popular music studies, we should try when we might to interview the high-profile subjects we study, doggedly chasing down ten minutes on the phone with Drake like we would a piece of the archive never-before-referenced in the proving-ground of academic journal publishing. Both are data, and both together create the most worthwhile picture.

Close-reading and textual analysis are established methods with a long and important scholarly history, and in the wake of New Criticism’s emphasis on understanding texts as self-contained aesthetic objects, the academy has produced generations of scholars capable of mining meaning unnoticed or unseen out of song lyrics and chord progressions. That is an incredibly worthwhile set of scholarly goals. But too often, I’d suggest, we do not supplement this reading—our own—alongside the subject’s own read. Neither invalidates the other, and they can and should be able to co-exist and not delegitimize our scholarship.

Part of this, again, must return to access. It is hard enough to get a famous musician or celebrity to sit down for an interview for a legacy publication without a trade of cross-promotional activity and branding. Until our academic journals start buying advertisements for Dereon Jeans, getting Beyoncé to hear our read of Lemonade as an social-justice invitation to a safe space of audience habitus is going to be a tough one.

But also—and I want to write this gingerly—what if our carefully constructed sandcastles wash away? What if our subjects disagree with our reads and we are forced to emphasize the subjective specificity in the face of disagreement from our inspiration? I recall (anecdotally of course) a friend’s disappointment upon watching director’s commentary on an old DVD edition of Spike Lee’s masterpiece film Do the Right Thing (1989). She’d left the viewing shaken (as many do on their first viewing) and moved by the moral complexities of Harlem and Mookie’s final decision. In the commentary, Lee was asked, “What was the right thing?” a question to which any answer would hurt the argument of some critic somewhere.

Fear of that kind of disappointment, I think, is part of why academics are often comfortable with analysis as a kind of academic write-around. That level of comfort runs the risk of perpetuating a cycle of lazy scholarship when more substantive data might be available and where our work might benefit as a result. A creator’s vision of events should in no way preclude us from explaining how other meanings and symbolisms adhere within their output. If our subject contradicts us, from that contradiction emerges new veins to mine.

So, again, this is not to say that the context-driven work should be altogether eschewed. But at the same time, we should be interrogating the structures of celebrity culture that births the subjects that so fascinate so many of us. This applies particularly when studying famous artists, who are most likely to generate the most Genius annotations, many of which are ultimately spurious or untrue. Media industrial structures have created an environment where quid pro quo produces much of the media presence of so-called celebrities. It is high time we ask a little more of them.

Has Kanye West read Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth? What would he think of it? Would Beyoncé connect her feminism to Kimberlé Crenshaw’s framing of intersectionalism? Was Jay Z’s 4:44 reawakening triggered by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s We Should All Be Feminists? Aren’t these questions worth asking?

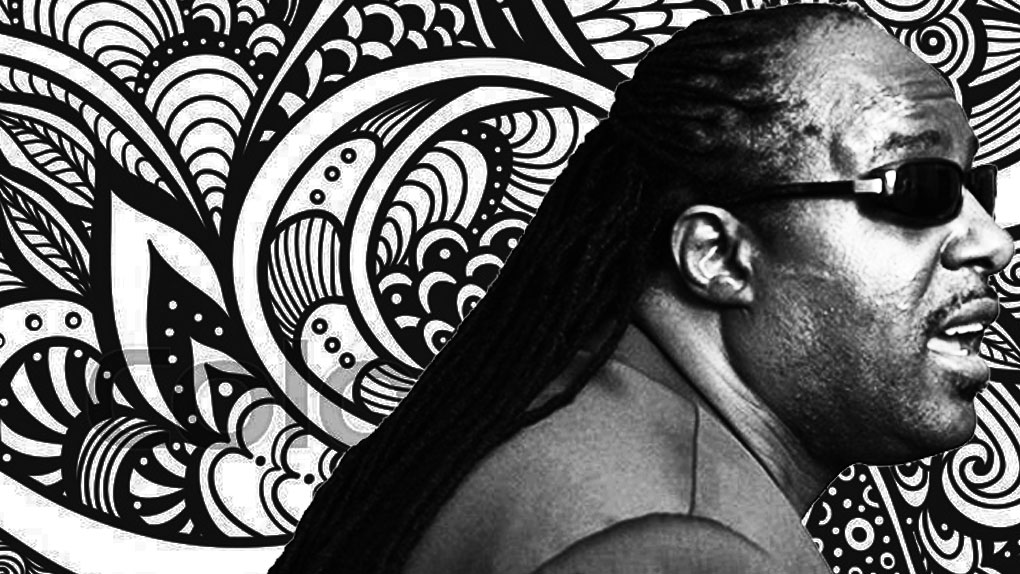

Relevant to my own work, I’ve recently defended my Dissertation Proposal, meaning I’m one (very large) step away from earning my PhD at the Annenberg School for Communication here at Penn: writing the dissertation. The study will effectively be a racial history of the GRAMMY Awards, using the awards and the discourse around them to understand how, in the recent history of the mainstream record business, black artists are appraised and racialized standards of “great” music emerge. The dissertation’s second chapter takes up the case of Stevie Wonder, who became the first (and eventually second and third) black Album of the Year winner, dominating the 1970s. Why was Wonder such an attractive figure for the Academy in a post-Civil Rights, post-King nation? The answer, this chapter suggests, is due to the confluence of two factors, (1) that Wonder’s combination of technical wizardry and proficiency made him perceived as a kind of superhuman figure whose skill allowed him to make auteurist music that transcended typical tropes around black music-making and (2) that his physical disability (blindness) and perceived squeaky-clean reputation made him an ideal token figure for industrywide admiration.

Wonder was seen as the ultimate technological expert—the liner notes to 1974 Album of the Year winner, Innervisions, credit him as having played every instrument on the album—pushing against usual, race-based narratives of black music as a product of a collective rather than singular voices. The argument goes, as Jack Hamilton’s Just Around Midnight (2016) suggests, that in industry discourses, many believed that white artists such as Bob Dylan produced creative work by virtue of their exceptional status, whereas black artists such as Sam Cooke were products of a race of people from which culture and art sprung. Wonder, we might argue, was seen as the first black auteur of the modern music industry era, and that being interpellated as such, combined with discourses around his disability, made him more willingly accepted by a resistant industry. Disability—usually a grounds for exclusion or inferiority—in this case became an unassailable argumentative factor for Wonder’s excellence.

My methods will include archival research to understand the discourse around Wonder in the mid-1970s; by reading Billboard, Variety, Rolling Stone, and various other trades of the time, I hope to paint a picture of how the industry was talking about Stevie and his greatness. Further, I plan to interview working journalists from the time and scholars of the Seventies, asking them to contextualize Wonder further within the social fabric of the times.

But why not see if I can get him on the phone, even if it upends the thoughtful framing I’ve outlined here? Why not at least try?

Either way, I’m ready when you are, Mr. Wonder. I’ll bring the tissues if you have a cold.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It