I was in the media room of the McColl Center for Visual Art in Charlotte, North Carolina where I’ve been an artist-in-resident for the last month, when a small opportunity was presented, one with powerful import. As I shared my experiences with the D.C. Boys and Girls Club Arts Camp from the previous weekend, the New York-based public artist Jackie Chang (also an artist-in-residence here) extended an invitation to accompany her on a field trip of sorts. The next day I (with three others) was on my way to the Youthful Offenders wing of the Mecklenburg County Jail to hear Ms. Chang speak to classrooms of young inmates about her work as an artist.

The dress codes for being part of such a visit are quite specific. The institution insists that visitors’ clothing be modest: you must avoid protuberant jewelry, open-toed shoes, and any other adornments that might distract the audience’s attention from the message of the day. Trading our various forms of identification for a visitors’ badge, we walked through what seemed like a maze of locked doors with our escorts, all under video surveillance. One couldn’t help but reflect on the surrendering of control and identity that occurs behind these walls. You could see it on the faces of our small group.

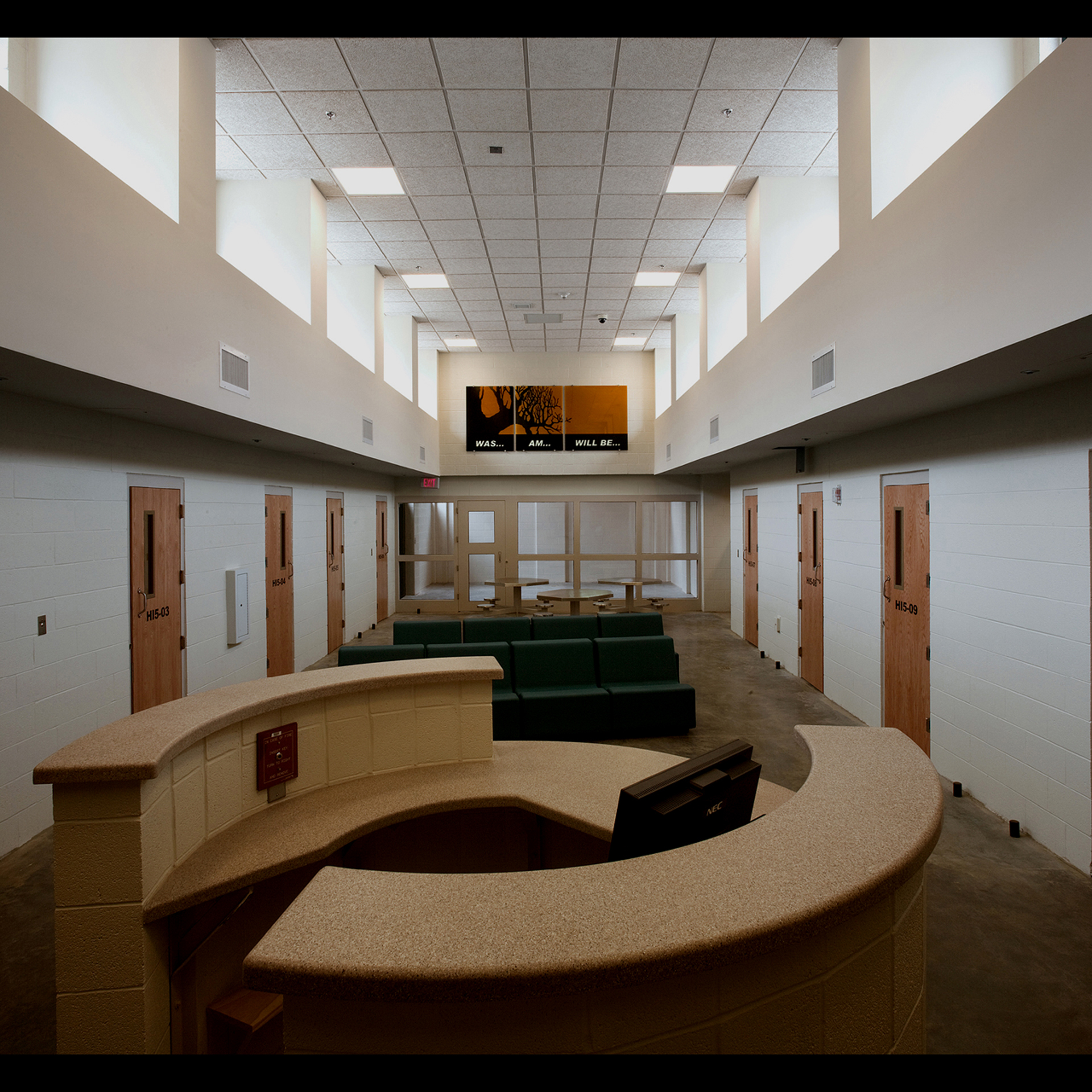

Chang was there to discuss a specific series titled Was/Am/Will Be. Made of glass and consisting of three colored panels, the pieces are fixed high above the common living areas called “pods.” The sandblasted words Was…Am…Will Be are set against the silhouette of a tree trunk, branches and leaves that splay across the panels.

It was remarkable to see the young faces of the youthful offenders. Ranging from 16 to 18-years old, most could have easily, with a change of dress, been mistaken on the outside for high school soccer campers or teen counselors or even pre-Freshmen in a college program. Instead, they were all identically donned in same-color outfits. And this strategic dampening of individuality was also reflected in the entire physical environment: in my view, the chosen hues and structural materials of the rooms and furniture worked to lull the inmates’ senses and outward expressions of such into a manageable conformity. In this somewhat sterile environment, even the heavy wooden doors of the cells themselves stood out as stark design elements, as Ms. Chang noted. The placid visual environment renders Chang’s work a noticeable trigger for conscious or, perhaps, unconscious reflection on the past, the present and future tenses of these young men’s lives.

It was remarkable to see the young faces of the youthful offenders. Ranging from 16 to 18-years old, most could have easily, with a change of dress, been mistaken on the outside for high school soccer campers or teen counselors or even pre-Freshmen in a college program. Instead, they were all identically donned in same-color outfits. And this strategic dampening of individuality was also reflected in the entire physical environment: in my view, the chosen hues and structural materials of the rooms and furniture worked to lull the inmates’ senses and outward expressions of such into a manageable conformity. In this somewhat sterile environment, even the heavy wooden doors of the cells themselves stood out as stark design elements, as Ms. Chang noted. The placid visual environment renders Chang’s work a noticeable trigger for conscious or, perhaps, unconscious reflection on the past, the present and future tenses of these young men’s lives.

Her presentation was stunning even as it was matter-of-fact. Rather than patronize, she informed three different small classrooms of young men about the genesis, creative processes, structural challenges and the creative vs. financial factors involved in mounting Was/Am/Will Be. Her “artist talk” could have easily been given in a corporate boardroom or at an artist retreat among peers.

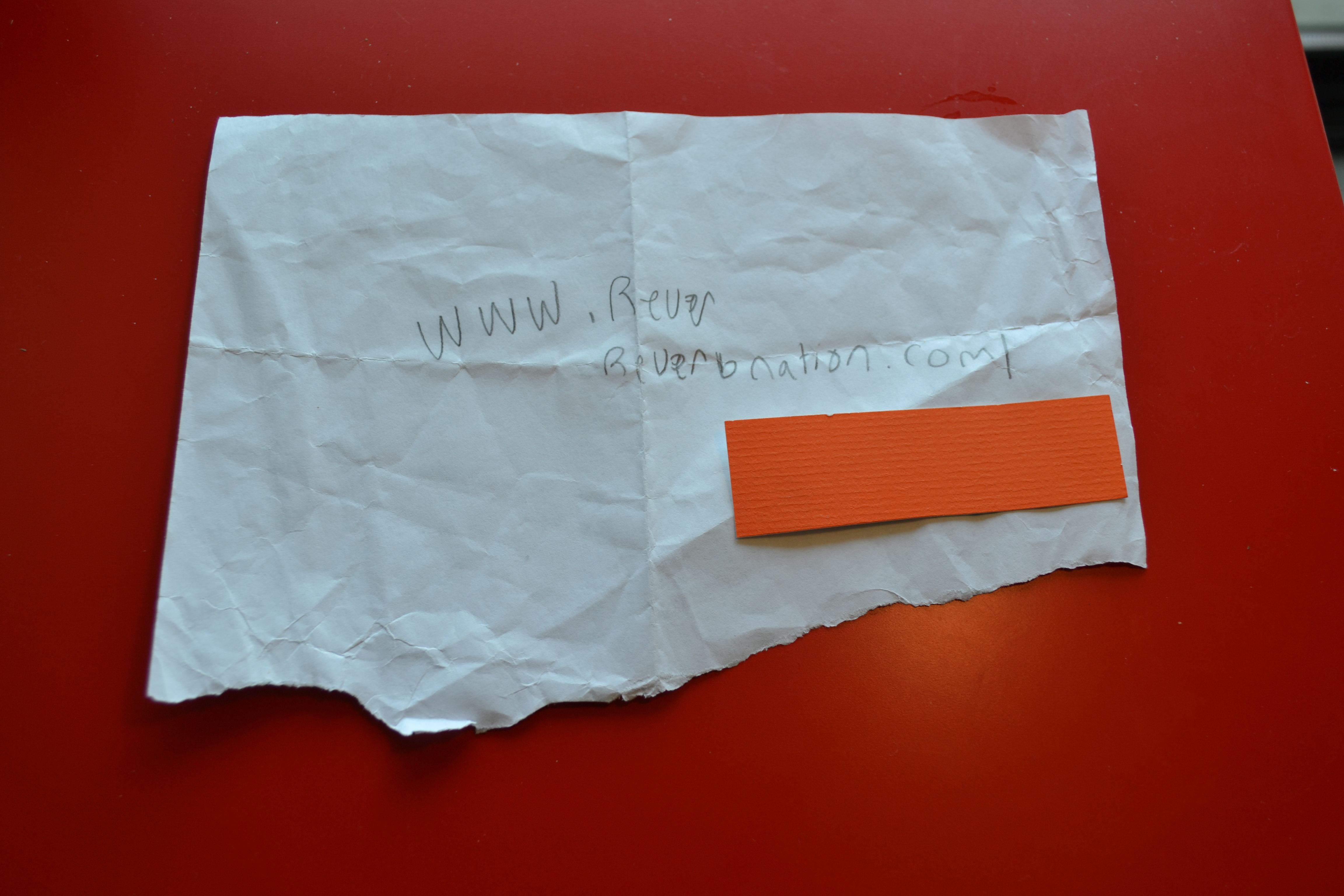

And the youth offenders’ responses to Chang’s work was equally remarkable and compelling—and for me heartbreaking. We learned of some of their artistic aspirations that included interior design and music even as some of them continued to work diligently through algebra problems with the same aplomb for multi-tasking that my Ivy League students work their social media during lectures. One young man wanted me to hear the music he’d created and scribbled his website information and implored me to give it a listen. (I did).

Like all young beat-makers and producers I’ve met, one youthful offender was eager for me to hear his music. He dashed off this handwritten note torn from his math workbook directing me to the (ironically named) ReverbNation website. I’ve obscured his handle after the forward slash. His beats are good.

We learned of their favorite authors. We learned about their curiosities about the money trail in the “art world” as well as how they could express complex, interpretive ideas about Was/Am/Will Be, and by extension, any piece of art, visual or otherwise. As we teased out various thoughts about the work, their impressive intellectual capabilities in the necessary conceits of abstract thinking became abundantly clear. Why, I thought to myself, couldn’t this conversation take place in a summer enrichment program rather than in this starkly ordered, predictable air-conditioned classroom within “the system”? Was this the first time that they had been exposed to this kind of activity? Is it the first time that their opinions were heard and mattered? Could it have saved them this mark on their citizens “record”? Might it have changed a past or present?

Ramsey pictured with artist Jackie Chang (with a “g” as she says) celebrating the final days of our residency at the McColl Center for Visual Arts.

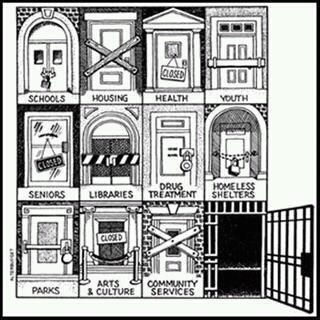

I didn’t want to leave. I applaud the partnership of the McColl Center and Mecklenburg County to program these kinds of opportunities. As I’ve written in a previous post about the importance of cultural arts in reaching at-risk youth, such engagements are crucial to creating alternatives to the individual and systemic pressures that caused the offenses of these youths to land them behind these walls. And, perhaps, the contemplation of Chang’s work riveted to these same walls can encourage them that their “will be” can also comprise other possibilities, ones not solely determined by a stacked system but in the power of creative thinking.

Tags: Jackie Chang, McColl Center for Visual Art, Public Art

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It