Things to See, Hear, and Read in ’11, Part 3

This spring Duke University Press (together with its admirable “editor’s editor,” Ken Wissoker) will release Kellie Jones’ much anticipated collected essays, and folk outside of the close-knit contemporary “fine art” world will see how she’s been, for many years, a fierce and fearless champion of African American, African, and Latin American art. They will also learn from this book what makes her tick. An art historian and curator trained at Yale University under the eminent Robert Farris Thompson and now teaching at Columbia University, Dr. Jones has written EyeMinded: Living and Writing Contemporary Art in a way that explains a lot—a whole lot.

One of the first lessons gained here is the power of her words to articulate formal descriptions of the processes, materials, and resulting objects of a wide range of important artists, including Betye Saar, Lorna Simpson, Al Loving, Howardena Pindell, David Hammons,

Choosing work in her father's archive for the show "Amiri Baraka Drawings" from 2009 that celebrated his 75th birthday

Jean-Michel Basquiat, Norman Lewis, Jack Whitten, and Kcho. Her interests in work across a wide range of visual media—sculpture, painting, installation, performance and conceptual art, film and photography—highlight a robust, ecumenical and non-preachy curiosity. Well, you might ask, “isn’t that what the best ‘eye-minded’ art historians do?” Indeed.

But EyeMinded furthers other agendas beyond formalism’s

delights. The often-rarefied air of the contemporary art world, especially as understood by and written about in the Ivy-League circles in which Kellie J trained and teaches, can be penetrated with other pedigrees. Here, the word “living” in the book’s title tells all. As the first-born of

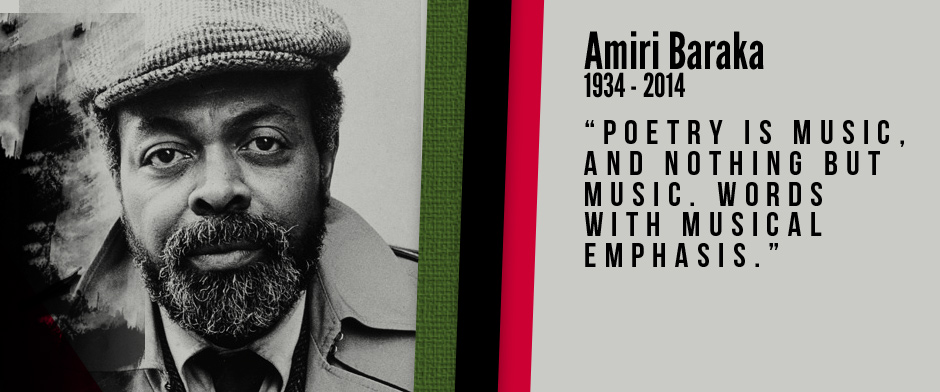

poets Amiri Baraka and Hettie Jones, Kellie J was raised in a world in which artists, musicians, and writers were actively and quite self-consciously finding voice. The rich introduction of EyeMinded details the importance of her early years in a milieu in which the social energies of black cultural nationalism and East Village bohemianism collided, shaping her view that art—and the artists themselves—

mattered. In essay after essay readers get to witness the growth of her voice as critic, curator, collector, and historian of living art worlds. If there’s such thing as

“street-cred” in fine art’s complex ecology of artists, collectors, curators, galleries, dealers, critics, museums, interns, and education programmers, you’ll find it here, flowing through the multicultural purview of Kellie J’s whose play dates as a kid took place in artists’ lofts and exhibition openings.

In the abstractionist Ed Clark's studio discussing her exhibition "Energy/Experimentation" for the Studio Museum in Harlem

Her family members, Papa B, Hettie J, sister-bullet-proof-diva Lisa Jones, and myself—provide what might be considered extended epigraphs to each of the book’s ample four sections, On Diaspora, In Visioning, Making Multiculturalism, and Abstract Truths. Pushing at the edges of the collected essay and monograph traditions, she includes these as examples of the dialogues of living ideas that first inspired her eye-minded-ness long

Sociologist and art collector Tukufu Zuberi gets a lesson in line and design at "Amiri Baraka Drawings"

before the Ph.D. seminar table and the scholarly conference. But would you expect anything less from the

Interviewing in Betye Saar's studio about Jones's upcoming exhibition at the Hammer Museum, "Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles, 1960-1980

gal who babysat for Archie Shepp’s kids, who somersaulted around Al Loving’s abstraction-filled studio, who au-paired for Jack Whitten in Greece, who heard Blues People being pounded out on a typewriter, who danced with Basquiat?

She makes a proper pot of collard greens, too, but no need to get too personal.

Tags: Amiri Baraka, Basquiat, Betye Saar, Duke University Press, Ed Clark, EyeMinded, Guthrie Ramsey, Hettie Jones, Kellie Jones, Lisa Jones, Samella Lewis, Tukufu Zuberi

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[VIDEO] Black Music and the Aesthetics of Protest](http://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/onlynchings1-225x225.jpg)