The other day I participated in a conversation on HuffPost Live with actor Gbenga Akinnagbe and attorney Ale Fernandez about “Stop and Frisk” and racial profiling practices. I joked on Facebook that I’d be talking about something I don’t study. I was reminded, however, that, I had experienced the long arm of the law in a case of mistaken identity. It was not my best day. Race and racism impact my life in particular ways, and music scholarship generally avoids direct confrontation with some of the uglier facts of human nature. But “it” must be acknowledged. Much of music history scholarship has tended toward ruminations on the beautiful. Music, as we know, can provide a reliable shelter from the struggles of everyday existence. Another characteristic of music scholarship is a different kind of problem. Scholars Richard Leppert and Susan McClary have critiqued this notion of “autonomy,” writing against the idea that music “shapes itself in accordance with self-contained, abstract principles that are unrelated to the outside social world.” We know that the social experiences of musicians, audiences and critics always shape what the music means. And all this reminded me of a piece I wrote last summer after spending some time among young men who experience life as one of the prime targets of the worse kind of racial profiling.

Watch the HuffPost Live segment here.

~Guthrie Ramsey, MusiQology Editor in Chief

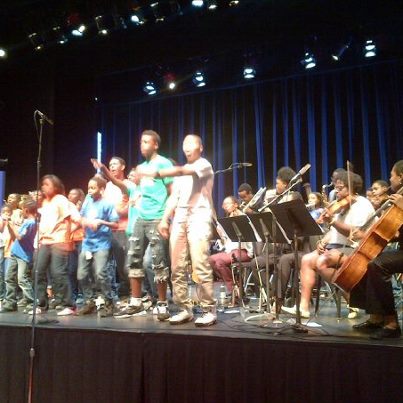

This past weekend I spent time with the Boys and Girls Club of the Greater Washington DC’s TAP (Teen Arts Performance Camp). The two-week, overnight program, which is in its fifth year, provided over forty children and teens the opportunity to get exposure to visual arts, dance, music and drama through intensive training with seasoned professionals. Cap-stoning their two weeks of relentless rehearsals, master classes, rap sessions and other activities, the campers presented three impressive performances in area venues, including the Kennedy Center and the DuPont Park Summer Stage. Directed and developed by master musician and arts educator Tony Small, the camp experience is designed to provide more than a laundry list of artistic skill sets. It also allows the campers to see models of leadership, mentoring, sacrifice and civility at a time when these principles are seemingly harder to come by in our everyday lives.

These are hard times. A bullying culture abounds among the young. And many of them are buttressed on the other side by state-sanctioned tactics like “stop and frisk,” designed to protect their own communities from their demographic group. Some kids grow up real fast in order to successfully navigate our present anti-youth social terrain, one in which arts education is disappearing.

These are hard times. A bullying culture abounds among the young. And many of them are buttressed on the other side by state-sanctioned tactics like “stop and frisk,” designed to protect their own communities from their demographic group. Some kids grow up real fast in order to successfully navigate our present anti-youth social terrain, one in which arts education is disappearing.

As I read it, TAP purposes to offer an alternative safe space for its campers, one that invites them to explore creativity as an outlet, as a key—as a tool to learn focus and discipline, and in turn, to use it as an avenue to discover their inner power and light. The final performances that showcased what they’d learned spanned styles from across the American musical landscape. We heard jazz, soul, rhythm and blues, gospel, hip-hop, Broadway, folk, rock, Motown, Afro-Latin, Caribbean, and fusion. They performed skits and danced tightly choreographed routines from all the major dance styles of the last century. And all these activities were shot through with elements of improvisation, an activity known to fire-up certain areas of the brain. It was a rousing and moving state of affairs for all involved: artists, audience, campers and parents.

As I read it, TAP purposes to offer an alternative safe space for its campers, one that invites them to explore creativity as an outlet, as a key—as a tool to learn focus and discipline, and in turn, to use it as an avenue to discover their inner power and light. The final performances that showcased what they’d learned spanned styles from across the American musical landscape. We heard jazz, soul, rhythm and blues, gospel, hip-hop, Broadway, folk, rock, Motown, Afro-Latin, Caribbean, and fusion. They performed skits and danced tightly choreographed routines from all the major dance styles of the last century. And all these activities were shot through with elements of improvisation, an activity known to fire-up certain areas of the brain. It was a rousing and moving state of affairs for all involved: artists, audience, campers and parents.

Recently I’ve read missives from various corners about very real anxieties surrounding what they see as the correlation between musical practice and the perceived ruin of our youth. Thoughtful disagreements circle around the relative value of this or that style (particularly jazz and hip-hop) for gaining ground in the fight to “reclaim” the young from the clenches of nihilism, bullying, apathy, all forms of bigotry, and to a certain extent, the various industries of mass mediation. What I witnessed this weekend makes me believe that we could focus less on determining the merit of readily available mass-mediated forms and more on the idea of broad arts immersion and sharing as a principle.

Recently I’ve read missives from various corners about very real anxieties surrounding what they see as the correlation between musical practice and the perceived ruin of our youth. Thoughtful disagreements circle around the relative value of this or that style (particularly jazz and hip-hop) for gaining ground in the fight to “reclaim” the young from the clenches of nihilism, bullying, apathy, all forms of bigotry, and to a certain extent, the various industries of mass mediation. What I witnessed this weekend makes me believe that we could focus less on determining the merit of readily available mass-mediated forms and more on the idea of broad arts immersion and sharing as a principle.

Elsewhere I’ve written about a “culture of sharing culture”—particularly to the generation below—that defined many social spaces of my own youth. When there wasn’t much in the material realm, there was nonetheless always something being passed along. One of those things for me, of course, was music. And I know from reading history that visual arts, spoken art forms, and dance at one time permeated the community, the church, the school, and the home. The sight and, and most important, the tangible feeling of witnessing the creation of an “achievement community” will be tough to forget.

Elsewhere I’ve written about a “culture of sharing culture”—particularly to the generation below—that defined many social spaces of my own youth. When there wasn’t much in the material realm, there was nonetheless always something being passed along. One of those things for me, of course, was music. And I know from reading history that visual arts, spoken art forms, and dance at one time permeated the community, the church, the school, and the home. The sight and, and most important, the tangible feeling of witnessing the creation of an “achievement community” will be tough to forget.

I can still remember powerfully what internal growth I experienced in such settings in my youth. This arts immersion model of leadership development, community building, sacrifice, and self-actualization works well. More of our youth should experience this mode of education.

The rhythm section, which included Scott McCormick, David Oliver, Nathan Jolley, and Victor Provost, brought the fire every night.

What a powerful image to see showbiz vet, Joe Coleman of The Platters fame, on the stage with the kids, singing his heart out in chorus after soulful chorus with the fortitude of someone forty years his junior. He entreated the younger performers singing background for him to not only join in the magic but to make their own as well. They believed him because throughout the week he, along with the other counselors and artists, had been teaching them other values outside of the music enterprise. That’s how you do it. Activities like TAP deserve our moral and financial support—involvement on any level is a must. Instead of “stop and frisk” we need to “stop and fund.” Our collective future depends on it.

It rained right before the final performance; it stopped suddenly and a double rainbow appeared. Some of the campers–many of them in other circumstances a prime target of “stop and frisk” policies–stood in awe and appreciation. One teenage boy asked me innocently as I passed, “Doc, what does it all mean?” Great moment.

Camp Director Tony Small and two teaching artists: Small’s daughter actress Shayna Small and violinist/Assistant Artistic Director, Juliette Jones celebrate the success of the camp.

Tags: Boy and Girls Club, David Oliver, DuPont Park, Guthrie Ramsey, Joe Coleman, Juliette Jones, Kennedy Center, Marvin Burton, Nathan Jolley, Rachel Winder, Shayna Small, TAP, Teen Arts Performance Camp, The Platters, Tony Small, Victor Provost, Washington DC

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[VIDEO] Black Music and the Aesthetics of Protest](http://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/onlynchings1-225x225.jpg)