It’s challenging to understand the meaning of slavery in American society even for the most prepared undergraduate student. While most know something about the institution—it’s horrors in particular—for many, it’s difficult to get a grip on how much it’s impacted the contemporary world. It’s something of which we’re very far removed. Nonetheless, expressive forms like music, visual arts, and literature allow us to engage the cultures of the enslaved as backdrops for understanding how it is a part of today’s artistic languages. It, arguably, remains an important reference point and conceptual frame for perceiving the distinctiveness of this thing called African American music. One thing is clear: the legacy of chattel slavery has underwritten much of what we think we know about blackness, invisible as the forgotten, tortured humanity that was the institution’s refuse may be today.

At the heart of the matter, it seems, is coming to terms—one’s own terms—with the idea of blackness and what and how it means as a social practice and not an “essential” identity. Although there are many great historical studies that unknowingly reduce these social processes to a state of biological ontology, I find the artistic imagination a wonderful means to destabilize this tendency. Indeed, musicians, poets, and visual artists have used the freedom that is the artistic impulse to balance the historical and contemporary, the material and ineffable, the personal and political responses to blackness. In this excerpt from her poem “Today’s News,” Elizabeth Alexander concedes consensus and embraces a vibrant sense of infinity:

At the heart of the matter, it seems, is coming to terms—one’s own terms—with the idea of blackness and what and how it means as a social practice and not an “essential” identity. Although there are many great historical studies that unknowingly reduce these social processes to a state of biological ontology, I find the artistic imagination a wonderful means to destabilize this tendency. Indeed, musicians, poets, and visual artists have used the freedom that is the artistic impulse to balance the historical and contemporary, the material and ineffable, the personal and political responses to blackness. In this excerpt from her poem “Today’s News,” Elizabeth Alexander concedes consensus and embraces a vibrant sense of infinity:

“I didn’t want to write a poem that said “blackness

is” because we know better than anyone

that we are not one or ten or ten thousand things

Not one poem We could count ourselves forever

and never agree on the number.”

While she relieves her art of the burden of defining what blackness is, she’s certainly clear about what blackness ain’t: one thing. Nevertheless, the historical record teaches us that it was derived from the fateful and globe altering encounter among the weapons and ships of European nation-states, the humanity of a perceived “Dark Continent,” and the rich natural resources of the New World. It was within this triangulation that something called blackness was calcified as a working concept.

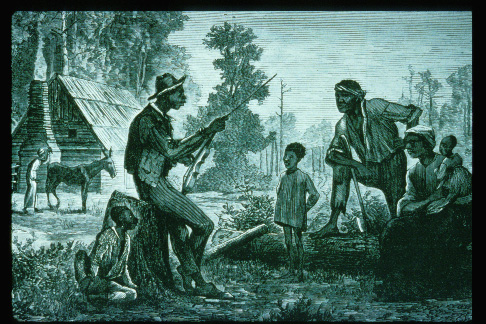

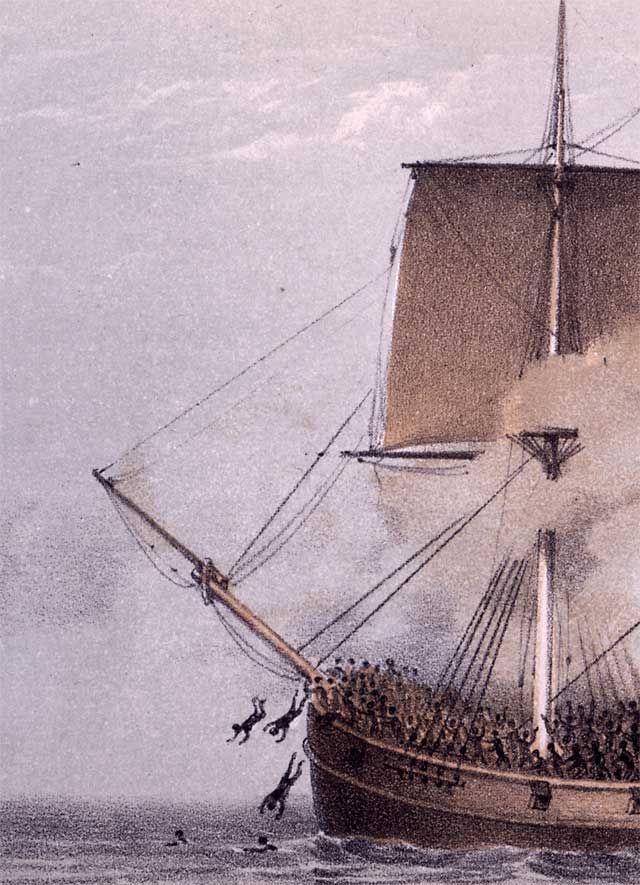

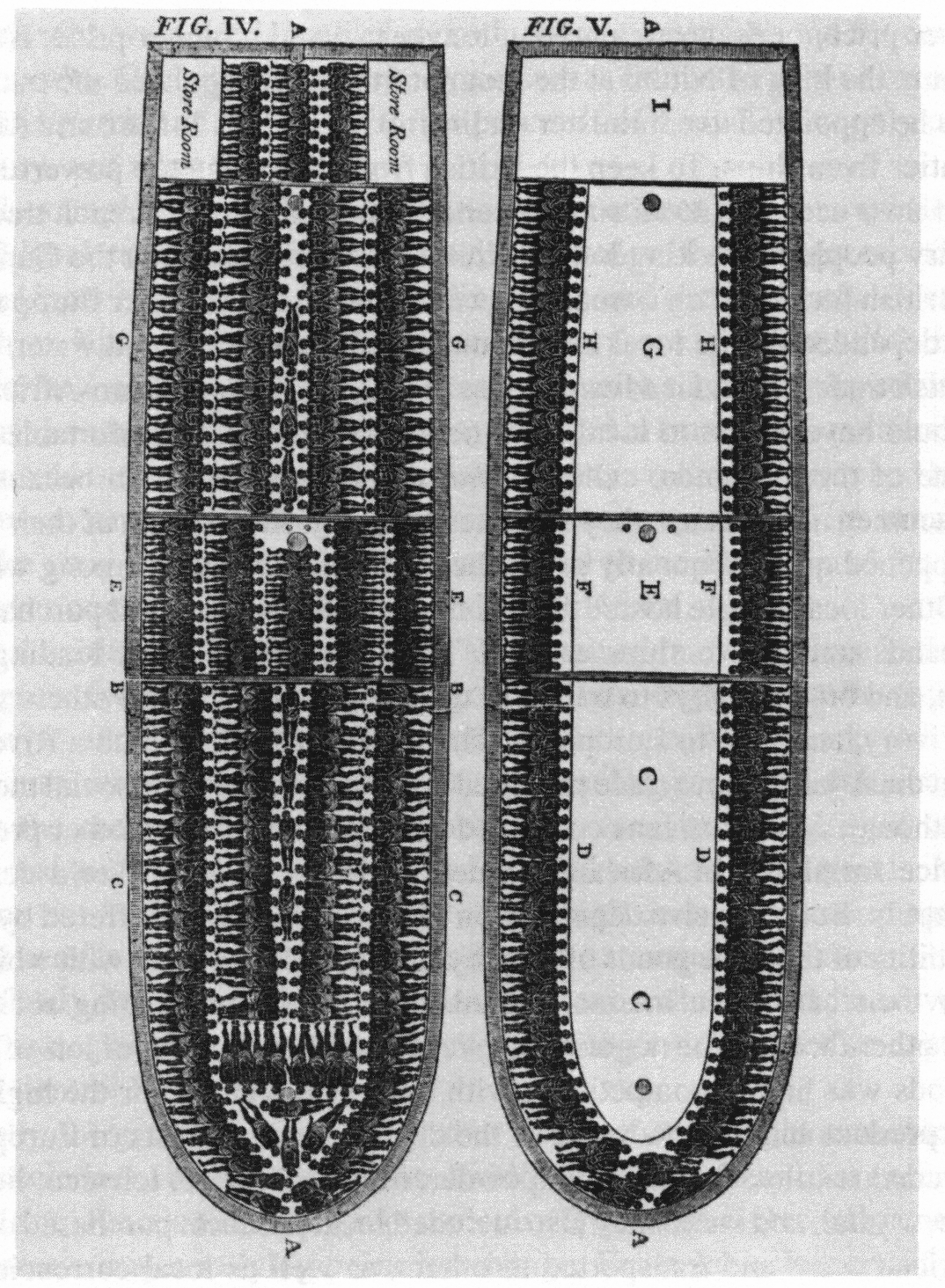

Between the fifteenth century and the mid-nineteenth century close to 12 million Africans were captured and transported to the New World, with the greatest number imported to Brazil and other locations in the Caribbean sugar industry. Reaching its apex between 1700 and 1820 when 6.5 million Africans were taken, the Atlantic slave trade represented one of the largest forced migrations in world history. Only six percent of the total number exported came directly to, what is known now as, the United States. These captured Africans were distributed along the eastern seaboard from New England to the mid-Atlantic colonies to the Southeast but the greatest concentration landed in the South.

Between the fifteenth century and the mid-nineteenth century close to 12 million Africans were captured and transported to the New World, with the greatest number imported to Brazil and other locations in the Caribbean sugar industry. Reaching its apex between 1700 and 1820 when 6.5 million Africans were taken, the Atlantic slave trade represented one of the largest forced migrations in world history. Only six percent of the total number exported came directly to, what is known now as, the United States. These captured Africans were distributed along the eastern seaboard from New England to the mid-Atlantic colonies to the Southeast but the greatest concentration landed in the South.

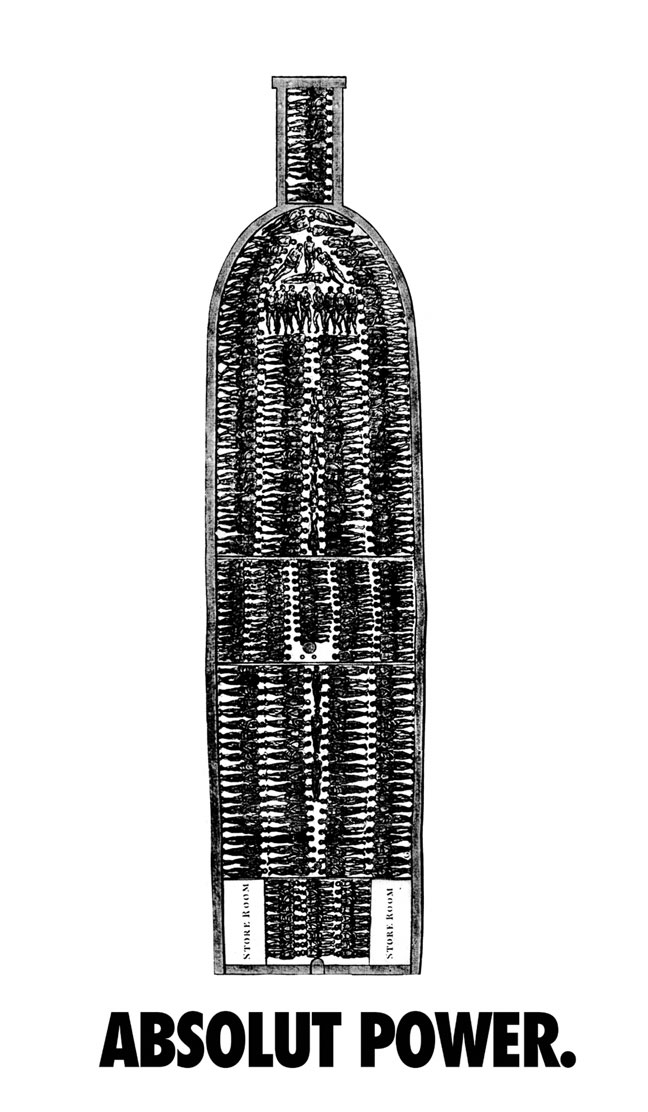

The horrors of “the capture” and the Middle Passage that transported the enslaved have been detailed in the historical record, theorized as the origin of a New World Pan-African consciousness, and have functioned as a flashpoint of artistic meditation. In “Outlandish Blues (The Movie),” poet Honorée Fanonne Jeffers imagines the Middle Passage as an urtext for blues culture even as she critiques Hollywood’s flattened out depictions of the journey. She asks in the first line of the first stanza of a poem eerily evocative of a Protestant hymn: “Where else can you sail across a blue sea into a horizon emptied of witnesses? Further down she writes:

“Before the food, water and mercy run low,

watch the celluloid flashes of sexy, tight bodies

that the sailors throw into the mouths of waiting fish,

bodies branded with the Cross, baptized with holy water,

tightly-packed bodies flashing across the screen,

Hollywood flat stomachs pressed to buttocks pressed to shoulders

first branded with the Cross, baptized with holy water

and then covered with manufactured filth.”

Detail from “Insurrection on Board a Slave Ship,” lithograph by W. L. Walton, in William Fox, A Brief History of the Wesleyan Missions on the West Coast of Africa (London, 1851), opp. 116, based on a black-and-white illustration in Carl B. Wadstrom, An Essay on Colonization, particularly applied to the Western coast of Africa … in Two Parts (London, 1794–95). Courtesy, Sheridan Libraries, Johns Hopkins University.

Conceptual artist and photographer Hank Willis Thomas has taken iconic material culture of the Middle Passage and used it as a powerful critique of contemporary society in his Branded series. As the art historian Cheryl Finley has argued: “Artists have found it important to insist on their connection to the history of slavery so that present generations can identify with it, forging a sense of collective identity.” This cultural memory work is a conscious and deliberate artistic choice and not a function of essentialism, according to Finley. “They use the pieces of their own experience to imagine the memory—to make it their own—in order to line themselves to the large group that shares the common memory.”

Hank Willis Thomas, Absolute Power, 2008

The nature of slavery in the United States was a singular enterprise, categorically different from various iterations of the “peculiar institution” throughout South America and the Caribbean. These distinct qualities shaped the development of African American cultural forms in dance, literature, visual culture and especially music. Despite the ingenious and hideous development of laws and social practices designed to keep black slaves subservient they nonetheless asserted their aspirations, senses of beauty and the sublime, their frustrations, pain, and humanity through sound organization.

North America began its philosophically “Western” existence as commercial and religious extensions of European powers. As such early black music making in this context must be understood in its relationship to European-derived musical practices. Although early religious music in the colonies represented a direct transplant from the Old World the Pilgrims indigenized it, and their music became rooted and influential. Musically simplistic and textually derivative, early American religious music would through a series of sonic and ideological developments become wholly “American” though in a persistent relationship—adaptations, rejections, and importations—with European models.

African American musical traditions mirrored these processes with respect to their relationship to the growing musical practices of the larger culture. These traditions constituted a confluence of broad African-derived approaches to sound organization and European-derived song structures and musical systems in a constant state of dynamic and historically specific interactions. What emerged is a composite: an indigenized conceptual framework of music making that has functioned through the years as a key symbol of an African American cultural identity.

The paradox of living as slaves and later as second-class citizens in a society founded on the principles of democracy and freedom produced a social structure in which black cultural production was mapped on a continuum between participation in what the scholar George Lewis has conceptualized as Eurological traditions and those reflecting Afrological aesthetic and structural priorities. Blacks who received training in Colonial-era singing schools are part of a long tradition of participating in Eurological practices that continues into the twenty-first century. Black music scholarship has generally included such musical activities by African Americans under the rubric “African American music.” From New Orleans to the mid-Atlantic to New York the historical record indicates a robust and varied musical culture among a new people created by forced mass migration, social domination, and heroic cultural resilience.

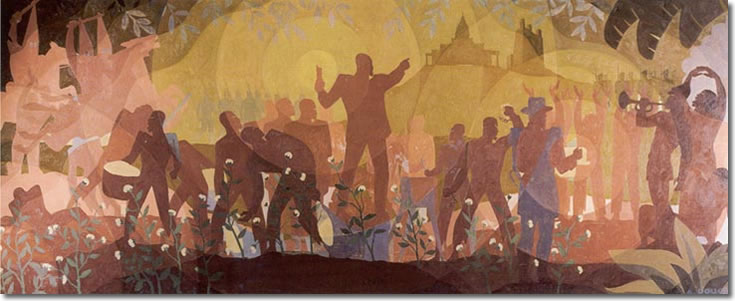

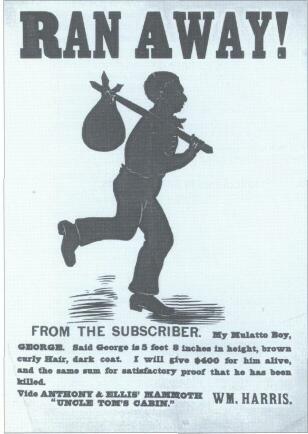

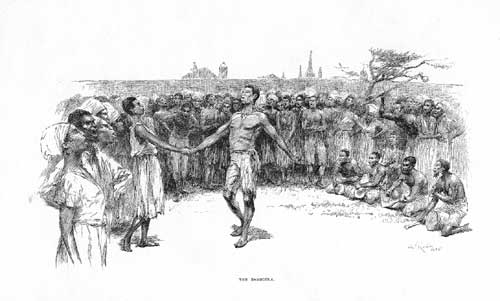

In letters from missionaries, slave advertisements, runaway slave notices, personal travel journals, and memoirs, white observers noted both the musical talents of and the distinct body of music making taking place among the slaves. Their writings, permeated in some instances with the desire to sensationalize what was considered “barbaric” in this practices, described the sounds they heard in rich and colorful detail. An 1867 account of a Pinkster Festival held in the 1770s describes an annual days-long celebration among slaves in Albany, New York. A conglomeration of dance, drum, and song, the musical components of the event provides a telling example of the cultural priorities of a people enjoying themselves during a rare time of repose from their lives as the “nonhuman” tools of their masters:

“The dance had it peculiarities, as well as everything else connected with this august celebration. It consisted chiefly of couples joining in the performance at varying times, and continuing it with their utmost energy until extreme fatigue or weariness compelled them to retire and give space to a less exhausted set; and in this successive manner was the excitement kept up with unabated vigor, until the shades of night began to fall slowly over the land, and at length deepen into the silent gloom of midnight.

“The dance had it peculiarities, as well as everything else connected with this august celebration. It consisted chiefly of couples joining in the performance at varying times, and continuing it with their utmost energy until extreme fatigue or weariness compelled them to retire and give space to a less exhausted set; and in this successive manner was the excitement kept up with unabated vigor, until the shades of night began to fall slowly over the land, and at length deepen into the silent gloom of midnight.

The music made use on this occasion, was likewise singular in the extreme. The principal instrument selected to furnish this important portion of the ceremony was a symmetrically formed wooded article usually denominated an eel-pot, with a cleanly dressed sheep skin drawn tightly over its wide and open extremity. . . . Astride this rude utensil sat Jackey Quackenboss, then in his prime of life and well known energy, beating lustily with his naked hands upon its loudly sounding head, successively repeating the ever wild, though euphonic cry of Hi-a-bomba, bomba, bomba, in full harmony with the thumping sounds. These vocal sounds were readily taken up and as oft repeated by the female portion of the spectators not otherwise engaged in the exercises of the scene, accompanied by the beating of time with their ungloved hands, in strict accordance with the eel-pot melody.”

Researchers have historically stressed the “functionality” of black music in comparison to that of the larger society and as a viable link to its “African past.” Nonetheless, Anglo Saxon Protestant religious expression was functional as well in Colonial America and as such became an important structural space for the development of African American music. As early New Englanders debated the value of oral and written modes of pedagogy and dissemination in their churches and singing schools well into the nineteenth century, African Americans codified their own musical sensibilities within the framework of their gradual acculturation into American Christianity. These qualities included performance practices with a predilection for antiphonal-response, timbral heterogeneity, rhythmic variety, improvisation, corporeal activity, open-ended structures encouraging endless repetition as well as oral dissemination. In 1819, John F. Watson, a black Northern minister criticized integrated camp meetings in which black musical practices were absorbed into the white church world, and his comments pointed toward a long-term pattern of cultural interdependence:

“In the blacks’ quarter, the coloured people get together and sing for hours together, short scraps of disjointed affirmations, pledges, or prayers, lengthened out with long repetition choruses. These are all sung in merry chorus-manner of the southern harvest field or husking frolic method, of the slave blacks.”

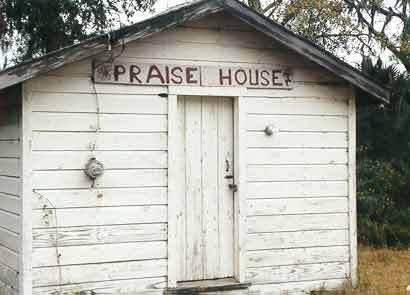

These practices made sonically porous the boundaries separating secular and sacred realms as slave festivals, holidays, and even revolts were accompanied by similar musical components, although the degree of “Africanisms”—those musical qualities with analogous connections to the historical (and in some cases, recent) homeland of the slaves—varied according to regional differences determined by the density of the black population in the relationship to that of the white ruling classes. Music became an iconic symbol of black difference and a recognized source of communal identity and, thus, inspired the passing of laws in selected states to control the social environment for fear of white safety.

These practices made sonically porous the boundaries separating secular and sacred realms as slave festivals, holidays, and even revolts were accompanied by similar musical components, although the degree of “Africanisms”—those musical qualities with analogous connections to the historical (and in some cases, recent) homeland of the slaves—varied according to regional differences determined by the density of the black population in the relationship to that of the white ruling classes. Music became an iconic symbol of black difference and a recognized source of communal identity and, thus, inspired the passing of laws in selected states to control the social environment for fear of white safety.

Between 1650 and 1750, the idea that African peoples formed a unified racial unit flourished in Europe as plantation slavery and its cultures shaped race ideology, trade economies, and social practices on both sides of the Atlantic. This construction of African identity was further entrenched in North America as black people founded churches, schools, and fraternal institutions during the decades surrounding 1800, many including the term “African” in their designations. The 1816 founding of the African Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia formally established a black religious tradition in the United States that would continue to develop within the institutional and structural systems of the larger society. The publication of an ex-slave, Reverend Richard Allen’s (1760-1831) hymnal A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns in 1801, affirms that the desire to engage in musical practices of their own making was part of the reason for the establishment of separate denominations. Following the tradition of printed metrical psalters of the New England compilers, Allen’s hymnal contains songs by Isaac Watts and others whose forms encourage antiphonal response among participants.

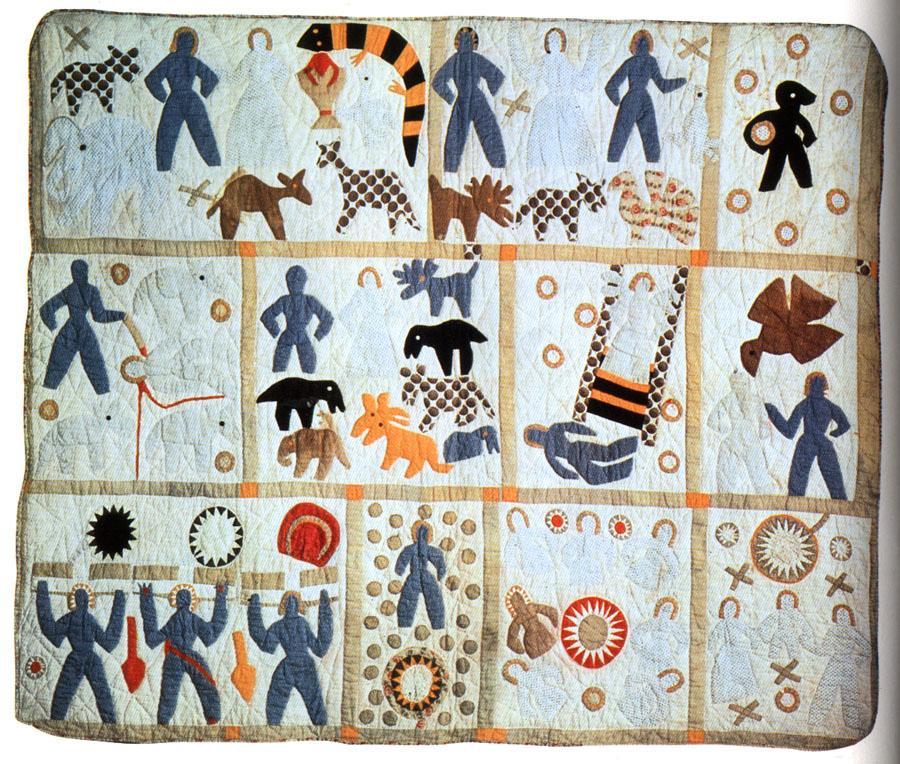

In the visual arts and in poetry we also witness a world being “made” from the Afrological artistic impulse. As Celeste-Marie Bernier reminds us, in the works of Dave the Potter (c.1780-1863) and the quilter Harriet Powers (1837-1911), we see how black subjectivity was being witnessed to and, in fact, created through artistic media.

“Dave’s highly visible poetic lines which he commonly situated near the rim of his jars”. . . argued “for the right of the black slave to an artistic identity.”

Harriet Powers used her patchwork quilts to preach the gospel using illustrated bible stories.

Harriet Powers used her patchwork quilts to preach the gospel using illustrated bible stories.

The pioneering art historian Robert Ferris Thompson has determined along with other scholars of literature, music, and religion that these artifacts and practices affirm the syncretic nature of Afrologics, and calls them a “flash of the spirit.” Not refusing belief in the magical, spiritual, and mystical in the face of skeptical rationality, he writes that: “Flash of the Spirit is about visual and philosophic streams of creativity and imagination, running parallel to the massive musical and choreographic modalities that connect black persons of the western hemisphere, as well as the millions of European and Asian people attracted to and performing their styles, to Mother Africa. . . . The rise, development, and achievement of Yoruba, Kongo, Fon, Mande, and Ejagham art and philosophy fused with new elements overseas, shaping and defining the black Atlantic visual tradition.”

The pioneering art historian Robert Ferris Thompson has determined along with other scholars of literature, music, and religion that these artifacts and practices affirm the syncretic nature of Afrologics, and calls them a “flash of the spirit.” Not refusing belief in the magical, spiritual, and mystical in the face of skeptical rationality, he writes that: “Flash of the Spirit is about visual and philosophic streams of creativity and imagination, running parallel to the massive musical and choreographic modalities that connect black persons of the western hemisphere, as well as the millions of European and Asian people attracted to and performing their styles, to Mother Africa. . . . The rise, development, and achievement of Yoruba, Kongo, Fon, Mande, and Ejagham art and philosophy fused with new elements overseas, shaping and defining the black Atlantic visual tradition.”

Whatever this thing called blackness is, poets such as Phillis Wheatley (“On Being Brought from Africa to America,”[1773]) and Langston Hughes (“Afro-American Fragment” [1959]) have reflected on the relationship of it to their own identities, even though they were separated by centuries. Their art and personal histories, like so many other African Americans across time and space were created within the logic of an African “presence” in America, a presence that is, as Elizabeth Alexander maintains, very much debated and is still “news.”

Tags: Afrological, Dave the Potter, Elizabeth Alexander, George Lewis, Hank Willis Thomas, Harriet Powers, Honoree Jeffers, Langston Hughes, Phillis Wheatley, Place Congo, Richard Allen, slavery

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It