While every day is a celebration of African American and Afro-Diasporic music here at MusiQology, the White House once again declared June to be the month where the nation recognizes the contributions of black artists from Bud Powell to Beyoncé and everyone in between. This month, as every month, we renew our commitment to the celebration of African American music, art, and artists. For more on African American Music Month, CLICK HERE.

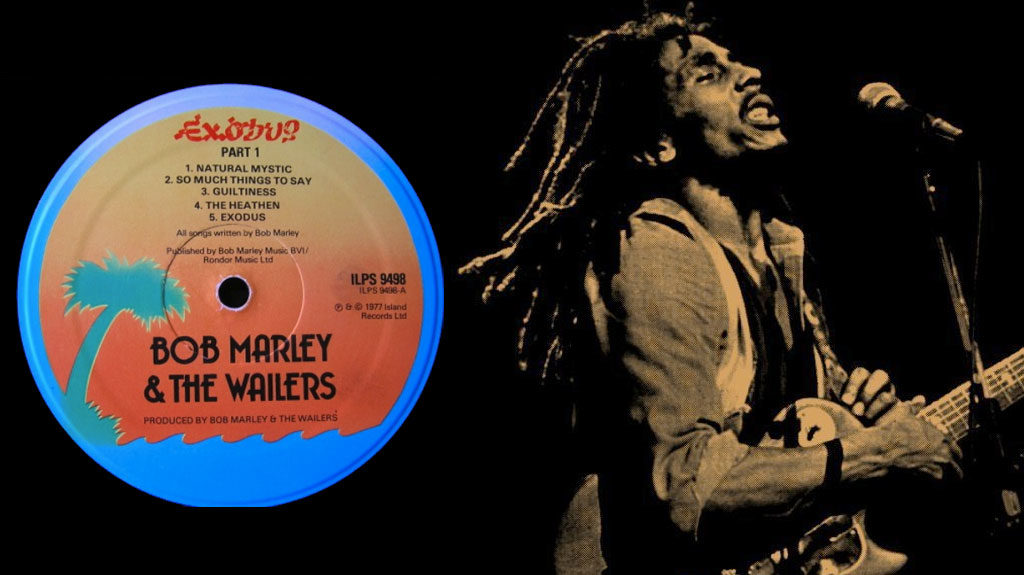

Forty years ago this past week, Bob Marley and the Wailers released Exodus, a canonical reggae album that captured a moment in the life of Marley and the world around him. In the months prior, Marley had been the victim of an assassination attempt at his home at 56 Hope Road; it was during his own physical exodus in London when he composed the album. But Jamaica—and the world—was beginning a global metamorphosis of multi-national industry as new manifestations of racial, national, and class supremacies rearranged themselves for a new era.

In the Seventies, the auspicious promise of Jamaican independence, awarded on August 6, 1962, began to unravel, with politically motivated gang violence gripping areas like Trench Town, the community housing project where a young Marley had learned the teachings of Rastafari and formed the group. By 1977, the government of Jamaica would agree to a deal with the International Monetary Fund for loans in exchange for structural adjustment, a set of policies that would lead to many more struggles for the island nation in the global economy.

It is in this context in which Exodus emerges, a ten-song collection of hopes, dreams, and criticism. It includes famous Marley hits like “Jamming,” “Three Little Birds,” and the ubiquitous “One Love,” but also more complex social commentary via “Natural Mystic,” “Guiltiness” and the title track. It received critical acclaim then and in the years that followed, but no honor means more than an acknowledgment from Time magazine in 1999. They named Exodus the album of the century.

“Every song is a classic, from the messages of love to the anthems of revolution. But more than that, the album is a political and cultural nexus, drawing inspiration from the Third World and then giving voice to it the world over,” they write. This album of the century designation is still a source of pride for Jamaicans; its cover art is painted on the brick walls surrounding 56 Hope Road, which now houses the Bob Marley Museum, a major tourist attraction in the island’s capital city.

While a relatively modest amount of time has passed, this “Album of the Century” designation deserves further scrutiny. What makes Exodus so important? And what is its continued relevance today? Simply put, the themes of Exodus are such that the album’s relevance did not stop at the dawn of the new millennium. In fact, Exodus is as much the album of the Twentieth Century as it is the album of the Twenty-First Century. Below are some major themes from our contemporary moment illustrated by the album.

Consciousness-Raising

“Natural Mystic” is often misrepresented as a specific person—Bob Marley, for instance, is often incorrectly called a “natural mystic” due to the song of the same name that opens the album. But instead, as the song itself suggests, “natural mystic” is a Rastafari abstraction—something blowing through the air on the wind across time and space, a mythic trumpet call from the Biblical Jericho, where the righteous Israelites (from whom some Rastafari suggest they are descended or reincarnated) used the power of sound to defeat enemies with whom they were at war. It’s a dark sentiment to open an album so pleasantly recollected by many—“Many more will have to suffer/Many more will have to die” doesn’t get recalled quite as often as some of the one-liners from later on in the album. But in an era of protest that we see today, many point to a global consciousness-raising at the root of the mainstreaming of collective action. From Black Lives Matter to the Arab Spring and the Occupy movements around the world, many might call it a natural mystic awakening protest and woke-ness in our contemporary moment.

Ideologies of Greed

Many of Marley’s songs are far more critical than the songs one typically hears at a local summer tiki bar. “Guiltiness” is one such example: it criticizes those “big fish” who “would do anything/To materialize their every wish,” hitting against the greed of the “downpressors” who oppress people like Marley and his fellow “sufferahs,” in Rastafari parlance. But note that it is guiltiness Marley criticizes—a sentiment rather than a person, which is made relevant by a line in the prior song on the album, “So Much to Say.” Marley transposes a line from Ephesians which reads: “Truly, our struggle is not against flesh and blood but against the principalities, against the powers, against the world rulers of this darkness and against the evil spiritual forces of the supernatural realms.” Our contemporary fight is of course against specific people responsible for inequity, but it is also against oppressive systems, a fact that seems to be entering the mainstream discourse now more than ever.

Mass Diasporization

This fact, more than any other, is the resonance of Exodus today: We are in a refugee crisis moment where vast swaths of humanity are being displaced from their homes and thrown into exile. As a result of conflicts like the Syrian civil war, the total number of refugees in our current moment—16 million, some say—is almost impossible to fathom. Our newsfeeds show pictures of innocent children killed as they wander in search of a safer homeland. And furthermore, with the continued damage being done to the planet, many more will be forced to leave their homes long before the end of the Twenty-First Century. The Exodus Marley speaks of stems from the enslavement and forced diasporization of African people during slavery; he preaches a return to the African continent as a way to set captives free. But Exodus will continue to be the status of much of humanity in this age, perhaps the greatest collective problem we face.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It