Trading Fours is a recurring column at MusiQology where we present the often-obtuse format of academic conversation in a more organized and easily consumable way. We set two voices in conversation around a theme or set of topics, restricting each contribution to four sentences, maximum. This keeps conversation concise and creates a more dynamic interplay to help ideas and through-lines flourish in a format that is more readable than most academic work. We believe it cuts to the core of MusiQology’s mission of accessible criticism with appropriate consideration and nuance.

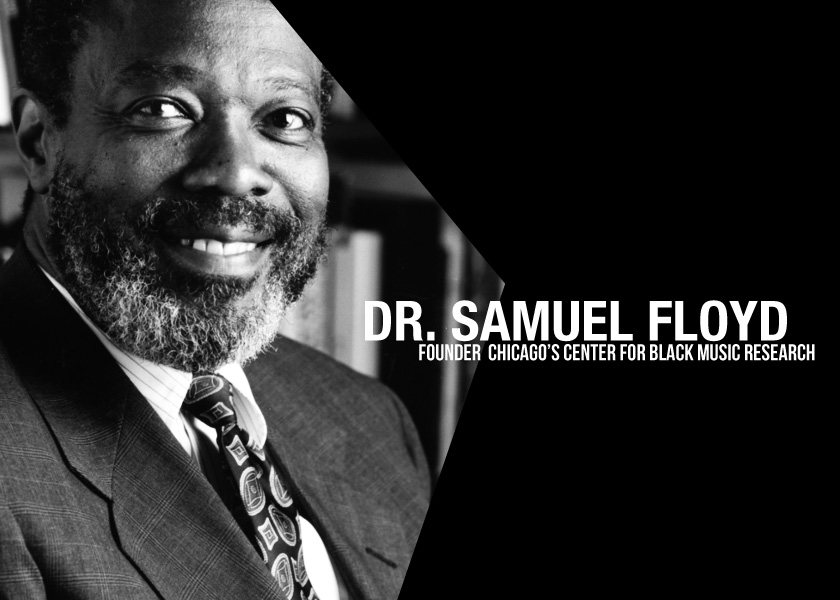

This week’s Trading Fours is a special one. Dr. Guy and John engage with the work of Dr. Samuel Floyd, examining his broader influence Born 1937, Sam Floyd was the founder of Chicago’s Center for Black Music Research and an influential and prolific writer and thinker. Most well-known for his work on the Ring Shout and Call-and-Response concepts, Sam’s work was fundamental for academics working to theorize black music on its own terms. He was a mentor to Dr. Guy and the founding editor of the Music of the Black Diaspora series at the University of California Press, which published Guy’s Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop in 2004. Sam also wrote many books, including The Power of Black Music: Interpreting its History from Africa to the United States, which is the subject of this installment Trading Fours.

Guy and John look back at The Power of Black Music, which Guy reviewed as an early-career scholar in 1998. After an introduction from Guy, discussing their relationship in depth for the first time ever in print, John and Guy (along with some help from Guy’s undergraduate students), talk through Sam Floyd’s role in the evolution of the academic study of black music and the power of his analysis.

Dr. Guy: I met Sam when I was an undergraduate or during my first months as a master’s student in music education. When I graduated college, I went right into elementary school teaching; I was not thinking about going into academia. I had a BA, I was a musician, and I said I was done with school.

But I kept reading this name in some of the research that I was doing — I kept reading about this man named Samuel Floyd. All of the music I was interested in thinking about and doing in my own career as a musician, he had written about. And then I learned the Center for Black Music Research, his institute that he started, was in Chicago, where I was. So I thought, “This guy is right downtown. I can perhaps meet him because I’ve just found his work so inspirational.”

And I did…I made an appointment and I went to see him. He was a tall, imposing man but warm and friendly. Very quiet. And I just knocked on his door and said, “I don’t know what it is that you guys do here, but I’d like to be involved. I want to do some research for you.” And he gave me this little project to do that today would have taken me two weeks, but it took me a year at that point. It turned out to be my first published article as a scholar, which was ironically about the lack of diversity among music professors in the academy. So I had to send surveys out to all of the schools of music and all of the colleges and universities in the Unite Sates and ask them how many black professors they had.

I’ll be frank: I had no desire to be one of them. When I was in an undergraduate situation, I felt sorry for my music professors. Because I said, “Oh my God, you could be practicing and playing and you’re…giving lectures and writing?! I just thought this was a complete and perfect waste of musical talent. That was, in my bravado years, what I thought. Because I was going to be playing in Wynton Marsalis’s band. Obviously I was — that was my goal.

So here I was being lured into this life of the mind and trying to collapse music and intellectual pursuits after I met Sam Floyd. And he saw me on the street in Chicago one day; we were downtown. And he said, “Ramsey, make an appointment to see me. I want to talk to you.” I said OK. And then during that meeting he said, “I’ve met a lot of musicians like you.” At the time I was in a master’s program part time; I was teaching elementary school; I had a church job…two or three of them. I had a full and robust life. But he said, “I see you all over the place. You need to consolidate, and I really think you would be a good music historian and I’d like you to think about that as a career path. I have a colleague of mine at the University of Michigan; they’re looking for people with your interests. Perhaps you should apply. I applied on a lark and much to my shock, I was admitted. I went through graduate school, landed a great job at Tufts University, and I had him to thank.

But meeting Sam Floyd was not the moment that changed my life. What changed my life with Sam Floyd was when he tried to hire me away from Tufts University to come work at the CBMR. This was not a true academic position; I wouldn’t be teaching as much as I do now. I would be mostly helping him be a researcher at the center. Can you imagine that when you feel like someone you owed so much to — a mentor — giving you this option to either come work with him or keep your regular academic position?

I chose to keep my regular academic position because I felt like it was more my calling. And he told me, “I’m so happy you’re doing what you believe is right for your own life.” His endorsement and support of me at that time in a field where there were just very, very, very few black people working…It just meant the world to me and it just gave me the full confidence to go and try to achieve everything I’ve achieved in this field. Because he believed in me.

Now…So I’m working as a professor and someone that I owed so much to has written this very, very important book. A book that, in fact, when I read the article that the book came out of, I believed, “I have a dissertation I can write.” I felt almost a spiritual connection with his writing. That I could…do this thing. And then so a journal calls me or writes me and asks me if I want to review the book. By my mentor, to whom I thought I owed everything to. So there we are.

John Vilanova: That’s a difficult thing to navigate, right? The best academic work is the type that makes an intervention, and one of the interventions that The Power of Black Music makes is the indexing, legitimizing, and putting down to paper a lot of stuff that was communicated orally before. Bringing analytical theory to something that was operating in a different space — it wasn’t always critical theory with a capital T. So what did you think your intervention could be when you set out to review this?

GR: I didn’t know what the reception was going to be in the academic community, so I wanted to make sure that I got my word in. Everyone in the field knew that I owed him so much — I don’t think it was a surprise that there was a relationship there. And I just felt like the book had been so powerful in my formation as an intellectual that I wanted to be one of the voices that weighed in on it publicly. So yeah, I just wanted people to know how important the book was…not only to me personally, but to the field in general.

JV: I think one of the important things that the book engages with (and I remember this appearing in your PowerPoint slides ten years ago) is the presence of tropes and that you could identify these recurring things in African American music. The tropes of African American music — identifying call and response and making that into an important way to understand, explore, and explain African American music. Take us to that moment and talk about what it was like to be reading something that was giving name to these things and setting them in this context. It made the study of African American music serious and standardized in a way that it hadn’t been before, right?

GR: I would shade it a little differently. The most important book in terms of legitimizing this field was by Eileen Southern, The Music of Black Americans(1971), which was the first major study that codified the entire history of African American music from slavery to the present. But that book was necessarily compensatory. It was a compendium based on all of this primary research, just laying out who was where and who did what.

JV: Were there others?

GR: This I interpret as the first major academic book that theorized through critical theory this history with Blues People preceding both of those but being the first statement that said, “Black music is political.” So if Blues People is about the political emphasis of this music, Eileen Southern was, “It’s more than just politics; It’s a full history with real people and events and institutions and social histories attached to it. Sam Floyd was, “This is a theory of this music.” I look at those things as being three different ways to think about it.

JV: We talk about history and how we can write people into history who were not there before, and I think what you were doing and what Sam is doing is writing practice into the discourse of the academy. So I’m curious — and this is a broad question, I guess — about the study of the African diaspora. The Middle Passage and trans-Atlantic slavery were processes that displaced people and therefore displaced history, so is our grand project, then, to reconnect those lines and to say, “Here’s what it is?”

GR: At the time, the thing that Sam Floyd had to deal with was that while people believed and understood that this massive flow of humanity came from Africa to the New World, there were debates about the degree to which cultures or food ways or worship patterns or how people made music survived that passage. It was really debated and so he was throwing the gauntlet down and saying that, “OK…It’s on the level of myth and ritual and the ineffable or the irrational that these tropes survived. And these tropes informed contemporary music-making.” And so he sought out chapter after chapter after chapter to build this case about why those connections animate what was going on in United States black music. If LeRoi Jones just made the assumption, Sam Floyd sought out to scientifically think about the irrational and the ineffable in black music.

JV: And in a way where the music and the troping and the continued existence of tropes — that becomes its own thing. It’s not a conventional history; the tropes themselves tell their own story and they progress across time in a way that’s not necessarily written in the history books. Because whose books are the history books?

GR: Exactly, and the next step of this process is the idea of Africa in Stereo. Where Africa does not just reside in the past of African American music; it is constantly reverberating back across to Africa and Africa is reverberating back to the United States. It’s not just frozen in the past. It is an active agent in the creation of New World black cultures.

JV: And that’s why at the Grammys when Kendrick Lamar puts Africa up on the screen and Compton is at the heart of it, right? Africa wasn’t just some blank slate where slaves were taken and nothing was left; it was a place where culture was always happening. There are a couple of things about the book that you talk about in your review that I think might be useful to parse out for everyone’s understanding of things. One is the distinction between survivalism and syncretism, which I think is connected to all this. Can you parse that out more clearly?

GR: For me, in this context, survivalism is this notion that we are still listening to African music if black people are making it. Syncretism is about the process where if there is a stereo going on between Africa and the New World, there is also stereo going on between all of the inhabitants of the New World, including white, black, Latino, Asian people…who are always informing each other’s cultures to the degree that we cannot say that anything is hermetically sealed. It is always a dynamic conversation going on. And that’s what we are always listening to.

JV: But in the context of America, let’s take the long-standing notion of America as a melting pot: What do we do with that? That’s a metaphor that has a long-lasting importance; but what does it mean to call it a melting pot and how do these specific metaphors do different things? Is it that everything melts into each other and that we are all America? Or is it like oil and water in the pot where they don’t merge in the way that the most hopeful users of that metaphor think they do.

GR: I have to say, too, is that as I’m re-reading this book with my class, there are still moments where I put it down and I say, “Wow. This is genius.” It’s amazing, especially as he goes through a single recording and talks about how it’s impacted…how his theory is impacted upon a single work that he’s able to sustain this argument throughout all of these time periods and genres and things. I just put it down and then think, “Wow. He was really trying to say something very important over these 300 pages.” I know that it was political; I know that it was something that he believed he had to do for his ancestors and for the people who would come behind him.

JV: Also let’s talk about poststructuralism in the academy at this time. It happens first–probably–with gender, right? That gender is not this binary thing, and when we think about it as a continuum it breaks down the structuring dichotomy that lasted for so long. So let’s relate poststructuralism to that in the context of this book and academic discourse to talk through what it is and what it means to the study of music and culture.

GR: For me, poststructuralism is this idea that how objects mean…how a painting or a piece of music means…can be understood first by understanding through an archeology of knowledge how an object can accumulate meaning through the investments that real, live, human beings place in it. It’s not ignoring its structure–its harmony, the rhythms, and all of that. Objects can have multiple meanings because the meanings are not solely inherent in the object; it’s always part of a conversation with the listener or the viewer. So that’s the basic crux of poststructuralism for me and there are all these theories that have taught us how objects are more than their form.

JV: One of the things, then, that we get to is talking about what a “fact” is versus a “social fact.” The most success we’ve had on MusiQology since I started editing it was our piece on Kendrick Lamar at the Grammys. I was mad, but I didn’t want to write a blog complaining about it, so what I started thinking about was, “What if I try to make an empirical case for what many of us take for granted as a social fact?” What is a social fact of black music broadly — the difference between affective factuality?

GR: I would say that the social fact would be the record. Let’s say the piece “Dippermouth Blues,” by Oliver and Armstrong…we could map out a schemata: “This is the intro; this is the first chorus; this is the first strain; this is the trumpet solo; this is the trumpet solo,” and we can just map it out like that and we can talk about a succession of musical events. But what moves it into this other realm of being a more dynamic object is when you apply some of the interpretations that Sam Floyd is doing to the object to say that it has telling effect and semantic value and rhetorical writing. Something is being written in the performance that communicates to people in the know and communicates to people who are familiar with the idea that meaning can move beyond the truth claim of a lyric, you know?

JV: Are there other examples of ways to theorize this with regard to black music?

GR: In my undergraduate class, we did a thing where we checked out some toasts–some Signifiyin(g) Monkey toasts — and we saw that on the formal level, you could say one thing, but when you look at the affective thrust of it, the rhetorical and cultural grounding of it is saying much more. It’s about power relationships. So it’s not just about performance, it’s about people negotiating who they believe they are in the world through performance. And that’s when things get dynamic and fraught — he always said things were fraught with meaning.

JV: You and Sam were both writing at the end of the twentieth century; Du Bois said that the problem of the twentieth century was the color line. And we can think about a lot of these books and a lot of this scholarship in thinking about that divide between black and white, conceding the existence of that and people having to figure out how to deal with it. When you had music and black music, the color line was the thing that divided those halves. So then the question in a big, open level way of thinking about this and the place of Sam’s work twenty years ago is: “What is the problem of the 21st century?”

GR: One of the things that I learned in this book about color lines, and it’s one of the things that I think could have been even more worked out (and I think Sam works it out in his next book, which will be published posthumously) is if you just take this trajectory from the Forties, Fifties, and Sixties that we just read, here’s his theory and then he has a tendency to place the musicians on some continuum in the theory. It almost seems as if the musicians are not making artistic choices, but instead ascribing to some aspect of the theory. For instance, the classical musicians who were black from this period who are in his argument “switching” to the myth and rituals of Western art music and not of the African cosmology, he’s still holding onto that dichotomy in the same way that it existed a hundred years prior. I wonder to what degree color lines are totally up for grabs at any historical moment, because people are not observing them in the same way. They tend to reconstitute themselves, but it’s a lot messier, I think, than the narrative presents it.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It