Managing Editor John Vilanova spent the better part of this past June in Tokyo researching the trade of vintage reggae vinyl and the current state of Jamaica-Japan musical relations. His research took him to a dozen record stores strewn throughout Tokyo and a soundclash that lasted past 5AM. Reggae inna Tokyo is irie — an influential and strong subculture that from which we can refigure our thinking about the orientation of what we perceive as the music industry writ large.

This is the first record press in Jamaica. It was imported by Jamaican businessman Ken Khouri in 1954 so that he no longer needed to rely on outside manufacturing to press vinyl. It also allowed him to record more indigenous/folk Jamaican music to sell to tourists. This press still exists, and sits mostly dormant at Tuff Gong Studios in Kingston, which is owned by the Marley estate. I was looking for vinyl that had been pressed on this machine and one website kept showing records for sale at Dub Store, a Japanese company that specialized in both vintage vinyl sales and offered pressing and distribution services for new recorded music. I found this strange—why was so much vintage Jamaican vinyl for sale across the world in Japan?

This, for instance, is a somewhat unremarkable 45 single from a not-well-known Jamaican artist. It was recorded in 1965 for Kentone records, named after Ken Khouri. This produced the first, most basic question guiding this research: How did this record get to Japan?

I started to research more, learning that reggae was actually a very popular subcultural entertainment for many Japanese people. There are multiple international festivals devoted to reggae each year; reggae-themed bars are present throughout Tokyo and Osaka; Jamaican artists play Japan with some regularity; J-Reggae is a flourishing subgenre; and Today, there are more sound systems—the massive speaker arrays from which reggae’s booming beats are most traditionally delivered in the live setting—in Japan than there are in Jamaica, itself. So I built out my goal, looking to excavate the industrial and cultural means by which Jamaican music gains and maintains a foothold in urban Japan. That produced the following two inquiries:

- What is the particular materiality of Jamaican vinyl in contemporary Japan?

- What is the role of the Jamaica-Japan relationship within the larger global industrial flows of music and recorded music? Why does their relationship matter?

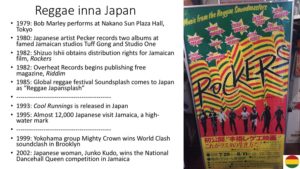

This is a brief history of reggae in Japan, broken down into three eras. Reggae itself originates in Jamaica in the mid-1960s, coming out of a blend of other indigenous Jamaican and Caribbean musics like ska, calypso, and rocksteady. Thanks in large part to Island Records and Chris Blackwell, an influential if controversial figure, Bob Marley became the first international reggae superstar, and the first globally successful musician from the Global South. Marley first plays Japan in 1979—this event was something that all of my interviewers of a certain age remembered. Additionally, many point to two Jamaican films—The Harder they Come by Jimmy Cliff and Rockers, shown here—as important texts for helping reggae spread globally. I interviewed Shizuo Ishii, who acquired the distribution rights for the film and screened it for hundreds of people in a week of showings in Tokyo in 1982. The golden age of reggae in Japan was the 1990s, including a large number of Japanese tourists visiting Jamaica. These trips were often organized by local entrepreneurs who would bring a dozen or so people at a time from Japan to Jamaica. The first trip, organized by Jay Inoue of Oasis Records, counted a man among its members who would go on to become Japan’s most famous J-Reggae artist, Rankin Taxi.

Marvin Sterling is the only major academic who has studied reggae in Japan. His book, shown here, is an ethnographic look at performance practices of reggae and Rastafari in Japan. Ultimately, he argues that reggae and Rastafari are lenses through which to view a range social identity—such as gender, class, ethnicity, and nationhood—in contemporary Japan. Complicating the centering of a West/Other binary might produce rich ways to retheorize cross-cultural relations. What I wanted to do was to take this theoretical imperative and use it as a way to explore the surprising industrial relationship between the two nations.

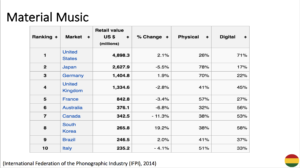

So the first way I do this is by looking at the materiality of music in Japan. As you see here, the percentages of music purchased digitally versus physically in the United States and Japan is flipped. Nearly 80% of music in Japan is consumed using material products. This bore out in my wanderings around Tokyo’s record stores—they have a massive Tower Records building and CD and record stores throughout the popular districts like Shibuya and Shinjuku. Many of these pictures were taken in mainstream stores, but there were also a number of smaller stores selling just reggae vinyl.

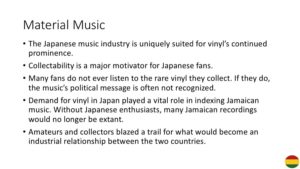

These were my ultimate takeaways from this ethnographic research on materiality:

During my time abroad, one of the things I learned was that the Facebook icon that shows the globe reorients itself based on your location. So rather than showing the Americas, in Japan it showed something that looked more similar to this, which I found on a sign outside of one of the dedicated independent reggae-only shops. This redrawing of the map can be hugely important when we query traditional music industrial arrangements.

People point to the collapse of the mainstream music industry as a leveling of the playing field, where independent labels are able to gain a larger foothold than in the past. We see here that Independent labels have more than a third of the market share in terms of label ownership. But the second graph here is important, because it suggests that distribution and distribution networks are a place where major, multinational conglomerates still control more than 85% of market share.

If we see that as a problem—and in my continuing work on the coloniality of music and media industrial organization I’m going to be arguing that we should—what then can we learn from the Japanese reggae case study?

The press at Tuff Gong is more or less out of use at this point, and vinyl—once the most culturally important way of accessing music in Jamaica—is in a massive downturn on the island. Artists instead are turning to the web, using Soundcloud and other digital distribution methods to get their music out. But what I want to argue is that there is still a strong market for vinyl, and that this surprisingly strong relationship between the two nations should not be forgotten. Earlier this summer, a collection of Bunny Wailer songs not released since 1973 were unearthed, remastered, and re-released by Dub Store. They’re remarkable songs, and this connection was the reason they were able to be heard again. The speed at which the digital has moved across the world has been striking and impactful, but for Jamaica, it has not been an unquestioned boon.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It