Good Life

While the lead-up was bloated, unwieldy, and inexorably behind schedule, Kanye West finally released his new album, The Life of Pablo, on Jay Z’s Tidal late Saturday evening. West held a surrealistic spectacle of a listening party at New York’s Madison Square Garden last week, with 1,200 “disciplined” models wearing his Yeezy Season 3 line as the Chicago rapper played tracks from the album over MSG’s PA system. It would take an additional two days for the final cut to surface after an appearance on Saturday Night Live, but mercifully, it is worth the wait: Eighteen tracks (a few of which are interludes) that affirm West’s position as the most ambitious and peerless artist of our time.

From the building choir swells of “Ultralight Beam,” West’s “gospel album” is aspirational and huge–the kind of contribution that upon each new listening will reveal more multiply-meant ideas and concepts. This is not easy listening; there is no “Gold Digger” or “Jesus Walks” here. Since the Taylor Swift incident (more on that later this week), I’ve always felt a kind of postmodernist twitch to West’s output: He became the person (on record, in public, and of course on Twitter) that his critics said he was. Here, West again is playing with perception — the stark depression of “Wolves” and “FML”; pained pathos on “Real Friends” and with his ascendant peer Kendrick Lamar on “No More Parties in LA;” and the desperate desire to make an impact on “Waves.” But now, the fame monster persona has subsumed the Old Kanye, the Louis Vuitton Don, and even Yeezus. Now Kanye’s looking to the Lord instead of declaring himself as such.

He’s of course not perfect (his record on women remains absolutely horrifying, and even his most ardent supporters can’t excuse the recent tweet in defense of Bill Cosby), and TLOP might not wind up revealing as much as we believe it can. But it allows us to use Kanye in the same way he’s been using himself — as a signifier. The absurd rollout of this album (just a week after Rihanna’s aptly titled ANTI) and the lack of an “industry approved” means of purchase is another death knell in a dying relationship. West claims to be $53 million in personal debt — is it possible for someone to have achieved so much “attention capital” at the risk of actual capital? And what can we make of the fact that so much of West’s capital has been stoked by his unlikability. West’s last album, 2013’s Yeezus was industrial and intentionally grating, an exercise in excess far different from his opus, My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy. How far could the music go? TLOP is more meditative: How much can music do?

Institutionalized

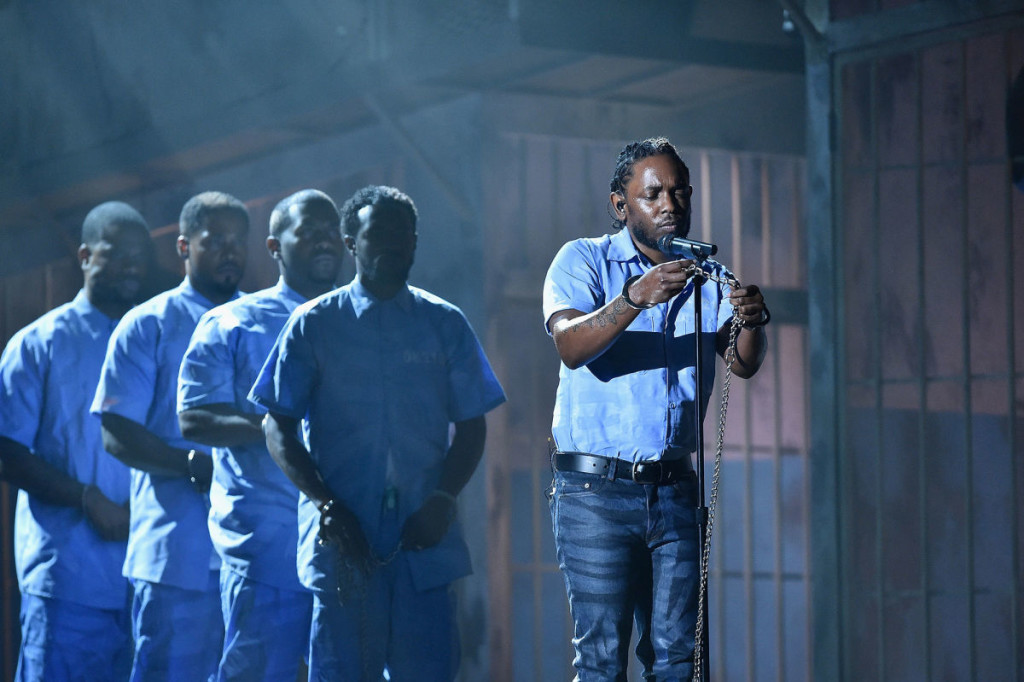

On a night which led the show with the awarding of Best Rap Album to Kendrick Lamar’s To Pimp a Butterfly, it seemed as if the Grammys were readying themselves to embrace a post-Ferguson, #BlackLivesMatter moment. The Weeknd performed. The cast of Hamilton accepted an award live from their sold-out Broadway theater. And Kendrick Lamar, he of the eleven total nominations, delivered a rhapsodic performance of “The Blacker The Berry” and “Alright” with his arms wrapped in chains, what one awesome blogger called a “transition from prisoner to griot,” and a Compton-as-Africa climax. We shouldn’t be naive enough to let music’s “greatest night” continue to disappoint us, but somewhere right around the time Neil Portnow paraded a 12-year-old pianist on stage to send a message to make sure listeners pay for their music, something seemed to go awry on the road to King Kunta’s coronation. And the end, mass market appeal trumped aesthetic excellence and pop conquered politics, with Taylor Swift’s soulless pop machine taking home the biggest prize of the night for her 1987 over Lamar’s superlative, of-the-moment masterpiece. It’s not that we should expect the Grammys to take a political stance, but Swift’s win epitomizes the out-of-touchness of bloated contemporary industrial institutions, hell-bent on celebrating their ongoing decadence when there’s a world of injustice, oppression, and pain going on outside their gilded walls. The year 2015 will be remembered for the 1,205 people killed by police and how Kendrick Lamar helped us cope. To Pimp a Butterfly will be remembered as the Album of the year, even if its excellence went unrecognized.

From the Green Room

Coming into this week’s Grammys, Snoop Dogg had been nominated for seventeen Grammy Awards. He has won zero Grammy Awards. Snoop had perhaps his best shot ever this year (he was credited on To Pimp a Butterfly); thankfully he wasn’t in attendance to experience loss number 17 in public. A few hours before Monday’s ceremony, he Instagrammed a preemptive plan for this year’s ceremony. “No need to blow smoke up my _ _ _,” he wrote. “I’d rather blow some real smoke with my loved ones.” The rapper has had a long-lasting and influential career, and his list of losses is an impressive and interesting survey of the state of the genre since his first nomination in 1994 (for “Nuthin but a ‘G’ Thang,” which lost to Digable Planets’ “Rebirth of Slick”). “Gin and Juice,” perhaps his most iconic contribution to the canon, was felled by Queen Latifah’s “U.N.I.T.Y” in 1995, a worthy defeat. But “Drop it Like It’s Hot” got two nominations in 2005, only to lose to Kanye’s “Jesus Walks”(acceptable) and The Black Eyed Peas’ “Let’s Get it Started”(not so much). He’s tried pairing up with pop stars (“California Gurls” in 2011, felled by Herbie Hancock’s all-star “Imagine” cover) and even reggae (Reincarnated as Snoop Lion in 2014, Ziggy Marley still took the crown). Snoop’s frustration epitomizes a moment in which artists of color are questioning more and more the validity of awards shows. Who is being rewarded? And for what?

Sliding White Fragility

Right wing cultural commentators aren’t quite done rattling their swords over Beyoncé’s halftime show, with Rush Limbaugh recently calling the performance “representative of the cultural decay and social rot” befalling our nation. Bill Maher hosted a panel during his show this past weekend, with Killer Mike (who was featured in this space last week) and Asian-American comedian Margaret Cho praising Queen Bey’s moment as other members of the out-of-touch political commentariat revealed their ignorance. There have been plenty of pieces explaining “Formation,” drawing connections and inspirations from formation-as-resistance rooted in epistemologies of marginal blacknesses to Michael Jackson-as-unseen-influence. But at the end of the day, it’s useful to remember that inexplicability has its utility, too. Speaking of what he calls “sliding white fragility” Mike provides listeners with an all-important reminder: “white people: It’s not always about you.”

Realization

In perhaps its most best sketch in years, Saturday Night Live also waded into commentary on who “Formation” is for with the video short “The Day Beyoncé Turned Black,” which ran during this past Saturday’s episode. Rather than recap it (it’s short and definitely worth a watch), let’s suppose that that was really the reaction of some fans out there. What then might it mean for “Formation” to be the thing that prompted white fans’ “realization?” Or more specifically, what about the song and video was different? Beyoncé’s blackness has been undeniable, but there’s something particular from an intersectional approach about “Formation” — the blackness she is claiming is not the mediated Illuminati/Roc-A-Fella brand. Instead, it’s Southern, queer-signifying (“slay“), and almost consciously anti-fame (Can you imagine Beyoncé eating at Red Lobster?). So to “turn black” is to “be black” in a way that isn’t for white listeners. It’s O.J. Simpson transitioning from crossover sports star to alleged murderer. It’s Kanye going from conscious nerd-rapper to arch-villain after interrupting Taylor Swift at the VMAs. And apparently it’s Beyoncé, who in owning a blackness that is uncomfortable to white consumers is aligning herself in a new formation.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It