“High Lights and Guiding Lights in American Music”

Birgitta J. Johnson (@DrBirgittaSays) is an Assistant Professor / Ethnomusicology / African American Studies at University of South Carolina. Follow her blog, Birgitta’s Music Box Review.

The Society for American Music (SAM) held its forty-first annual conference in Sacramento, California last week. The Society’s mission is to “stimulate the appreciation, performance, creation, and study of American musics of all eras and in all their diversity…” and as one of the premiere academic music conferences in the country, this year’s meeting delivered on those goals. Hosted by the University of California, Davis and held at the Sheraton Grand Hotel in downtown Sacramento, this year’s conference was packed with exciting and innovative presentations by musicologists, music educators, ethnomusicologist, musicians, dance scholars and music theorists.

While not exhaustive, here are a few highlights of my personal favorites from the conference as well as two historic moments honoring two giants in the field of African American music scholarship and life time service to the promotion of the study of African and African American music and culture nationally and internationally.

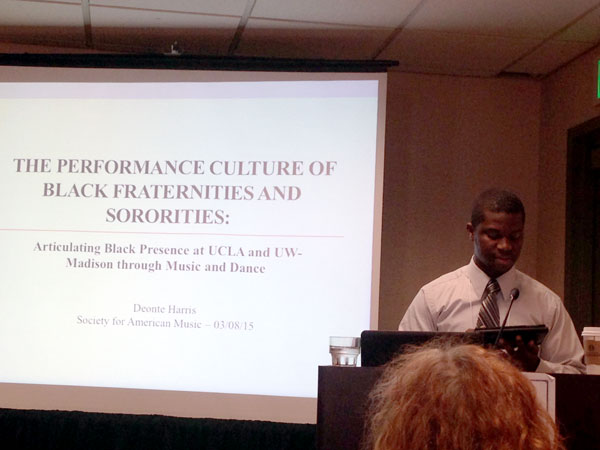

Deonte Harris presenting his paper, “The Performance Culture of Black Fraternities and Sororities: Articulating Black Perspectives at UCLA and UW-Madison through Music and Dance”

Thursday included a dynamic panel on West Coast gospel music hosted by the Gospel and Church Music Interest Group. This was the only Interest Group panel dedicated to an African American music genre during the conference this year. As the panel abstract notes,

In the 1970s the West Coast emerged as one of the thriving centers of a new contemporary style of gospel music. This style represented the emergence of a new generation of voices (compositional and performance) that would shift the sonic, visual and theological context of gospel and reflect–intentionally and covertly–how the politics of the Civil Rights and Black Power Movements impacted new readings of black spirituality…

The session was to consist of three papers that would investigate the “compositional and performance pursuits of significant artists who helped establish the Bay Area and Los Angeles as two of the prominent musical centers for gospel music during the 1970s and 1980s, namely the significant artists discussed were: James Cleveland, The Hawkins Family, and Andrae Crouch. However, the paper “Church Mothers and Soul Brothers: Listening to the Music of Reverend James Cleveland in the Era of Black Power” could not be presented due to a last minute emergency. Nevertheless the session was filled by papers on Cleveland’s heirs in the realms of gospel music innovation. Deborah Smith Pollard (University of Michigan-Dearborn) jump started the hour with “Oh Happy Day: From 18th Century Hymn to Gospel Music Game Changer.” Pollard brought new layers of thought around the 1967 song and group who kick started what now is considered contemporary gospel music. While the sonic innovations of “Oh Happy Day” have been thoroughly addressed over the years, Pollard delved into the lyrical distinctiveness of “Oh Happy Day” as well as how the Hawkins group “…created a new youth-centered performance aesthetic” that included “dynamic changes in instrumentation, attire, and representations of gender.” As Bay Area ambassadors of the new sound and style in gospel, the Hawkins and the controversy they sometimes elicited from church folk, predicted many of today’s current tensions around the presentation and performance of gospel music by young people who are increasingly less concerned about gendered protocols around styles of dress and appealing only to church-going audiences.

Southern California would not be left out of the party during the session. “Race, Rhythm, and Religion: Chronicling Andraé Crouch’s Dual Role as Contemporary Christian Music Pioneer and Gospel Music Trailblazer” by yours truly, Birgitta Johnson (University of South Carolina), rounded out the session by tackling the awesome early career of the late Reverend Andraé Crouch. Crouch’s recent passing in January 2015 impacted the paper’s focused attention on his very first years prior to dominating and innovating two separate Christian music audiences and industries for several decades. Crouch’s upbringing in racially diverse Pacoima, California and his early contact with multi-racial missionary and youth ministry groups contributed much to his broad reaching approach to song lyricism as well as his boundary-less approach to musical genres, both sacred and secular. Just a few years after penning communion and gospel music standard “The Blood Will Never Loose Its Power” at only fourteen years old, his production and performance role on Teen Challenge Addicts Choir in 1968 (Word Records) laid the foundation for Crouch’s ability to not only navigate between the highly racially segregated worlds of Contemporary Christian music audiences and (black) gospel audiences but also Crouch’s wholesale command of secular music influences such as the muted trumpet-laced blues lament, “The Addict’s Plea,” that heads off the album and could rival Donny Hathaway’s later hit “Giving Up” in tone, timbre, and mood. Other rousing moments from this discussion included the examination of racial dynamics and social commentary around racism within the Christian community cleverly packaged in a 1977 comic book On the Road with Andraé Crouch published by Spire Christian Comics and illustrated by the legendary Al Hartley of the Archie and Atlas comic series. Among the typical biographical and evangelistic bend of the comic, the story lines include several instances where Crouch’s character and that of his African American band members experience racial discrimination and outright rejection from Anglo-American Christian audiences during the early days of his career. Incidents that Crouch would eventually speak more candidly about later in his life, were momentarily captured in graphic cartoon form at a time where Andraé Crouch and the Disciples literally traveled the world with America’s leading Christian evangelists just as easy as they graced the stages of Johnny Carson’s Tonight Show and New York’s Carnegie Hall.

On Saturday, the room was packed for the “Jazz and Gender” panel chaired by Sherrie Tucker (Swing Shift: “All-Girl” Bands of the 1940s). That there was even was a panel for jazz and gender was not a point lost on the audience or the presenters who came with plenty of heat and new narrative pushing scholarship. Yoko Suzuki’s “The Battle of the Vibes: Politics of Race and Jazz during the 1950s” jump started the awesomeness of the hour. Not only including information about unsung bebop pianist and vibraphonist, Terry Pollard, Suzuki (University of Pittsburgh) presented in-depth interviews with Pollard’s biggest champion, band leader and vibe duet partner, Terry Gibbs and other members of Gibbs’s band who also played with Pollard. While Pollard and Gibbs never recorded any of their famed vibe battles, Suzuki shared an awesome video clip of their 1956 Tonight Show appearance posted to Youtube by Terry Gibbs after Pollard passed in 2009. Suzuki did a great job piecing together how through music and mutual respect of each other’s talents Gibbs and Pollard navigated race, gender, and sexuality in pop music performance at a time when the two of them could not stay in the same hotels in most parts of the country and when most of Pollard’s female jazz compatriots from the war years had returned home to resume their lives as housewives and mothers.

Tammy Kernodle presenting her paper, “Be Real Black for Me’: Roberta Flack, the Quest for Artistry, and the Shifting Context of Blackness in ‘70s Popular Music”

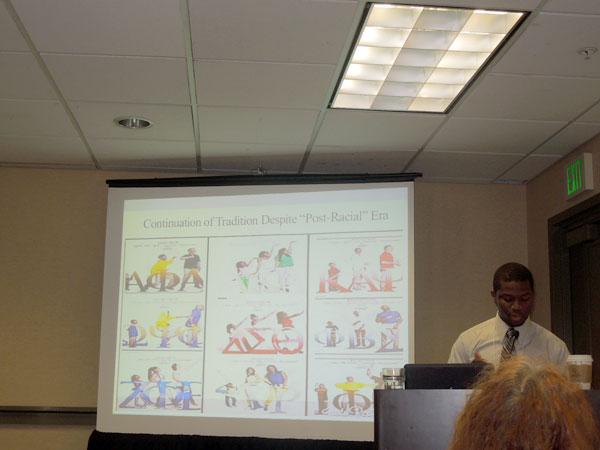

Deonte Harris presenting his paper, “The Performance Culture of Black Fraternities and Sororities: Articulating Black Perspectives at UCLA and UW-Madison through Music and Dance”

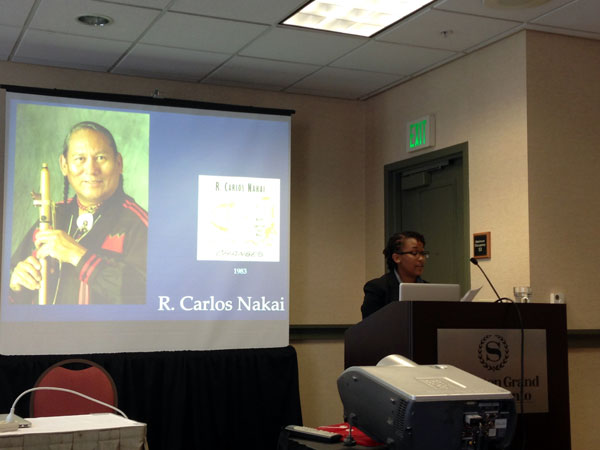

Rose Boosma (UCLA) presenting her paper, “The New Age Pastime: Appropriating the Native American Flute”

Ryan Bunch (Rutgers University-Camden) presenting his paper, “Bursting Into Flight: Animated Bodies and Adolescent Desire in Musical Films of the Disney Renaissance”

Next in the panel was “Black Radio/Music Society: Examining Gender Politics of ‘Post-Genre’ Jazz(?)” by Heather Anderson (University of Texas -Austin). By the first five minutes of Anderson’s presentation comparing the gendered and racialized receptions and perceptions of Robert Glasper’s Black Radio and Espernza Spalding’s Radio Music Society, I literally wanted to yell out “THE CHAMP IS HERE!!!” in my best Will Smith doing Muhammed Ali. We got representative song samples from both albums and an impressive weaving together of traditional gender critique with contemporary reads of the album projects by heavy hitters Mark Anthony Neal, Greg Tate, and Guthrie Ramsey. There was also Anderson’s own deft handling of the levels of bias and even misrecognition Spalding contends with when facing some of the same limitations Glasper gets to side step due to privileging of male instrumentalists typical in jazz compounded by pop culture’s acute privileging of (male performed) hip-hop music when it comes to reading “innovation” and “marketability” in mainstream music outlets by jazz critics, black media, and pop outlets. I hope this gets an article treatment as soon as possible because getting our lives doesn’t even remotely describe the audience’s response to what was brought in that twenty minutes.

Lastly was the legendary and newly retired Judith Tick (Northeastern University) with “Ella Fitzgerald’s Scrapbooks: New Sources for a Revisionist Interpretation of Her Early Career.” Let that sit with your consciousness for a moment: ELLA FITZGERALD’S SCRAPBOOKS. Yes, her actual scrap books accessed through Ella’s son for research, and yes—more than one. Beyond the sight of ephemera and scraps of memories chosen by Ella’s own hand from the late 1930s and 1940s, Tick peeled back the layers of a famed bidding war and headline attracting feud over Fitzgerald between mainstream America’s “King of Swing” Benny Goodman and the band leader with whom she launched her journey towards jazz immortality, Chick Webb. Combing through historical accounts of the alleged $5000 offer for Ella’s contract with Webb by white jazz journalists and the very New Negro-focused tenor of black news outlets like the Pittsburgh Courier reveal the very familiar gender-race bind Ella and many black female performers would find themselves in back the up until about five minutes from now. So just in case somebody tries to tell you black male privileging over black women (and their bodies and their art) is not real, the news clippings Dr. Tick presented over the fiasco and subsequent face saving Fitzgerald ended up doing for both Webb and Goodman (and the male dominated music industry, truth be told) should do much to challenge that perception. Fortunately, Ella’s runaway/escape/time out from Webb’s band was brief considering that the story breaking that another band leader approached Webb or her management for such an opportunity (read visibility upgrade) and she basically had to learn about it in the streets. While it meant a possible delay to her jazz superstardom and financial independence, Fitzgerald automatically received the seal of approval as a “race woman” among a black community who were planting the seeds for the Civil Rights movement just a few decades away.

Tick yielded the end of her presentation for what has go to be the best audible in conference paper history: a possibly one-of-a-kind live recording from 1986 of Ella singing Benny Goodman’s “Goodnight My Love,” from 1936 for the film Stowaway starring Shirley Temple and Alice Faye. It was provided by James Blackman, a friend of Ella’s in her later years, who briefly served as her road manager and who was also in attendance at the conference. In the sound clip, Ella speaks highly of Goodman and pours out much tea by mentioning that her “name had to be taken off of the record because it was a hit” and she was signed with “another band leader” at the time. Besides the thoughtful tribute Fitzgerald gave Goodman weeks after his death, the audio marvel was that the performance was captured two months before she would go into surgery for respiratory problems and quintuple bypass surgery, and her live vocals then could still top 95% of the vocals in the Top 100 today.

The range of developing research and scholarship in the vast field of American music culture past and present was well represented at this year’s SAM conference and definitely beyond explorations of transcription and lionization of carry-overs from European art music traditions (I swear that was not disciplinary conference shade, friends. Don’t shoot.). The “Defiance and Survival on Film” panel brought a fresh gender retrospective and nostalgia worthy presentation of an iconic animated production company in Ryan Bunch’s “Bursting Into Flight: Animated Bodies and Adolescent Desire in Musical Films of the Disney Renaissance.” And Eastman School of Music’s Maria Christina Fava rounded out the panel with 1950s camp and B-movie as survival during the Red Square in her paper, “Surviving McCarthyism in Hollywood: Elmer Bernstein and Robot Monster. Other “Amen” inducing student presentations include Deonte Harris (UCLA) and “The Performance Culture of Black Fraternities and Sororities: Articulating Black Perspectives at UCLA and UW-Madison through Music and Dance.” Little did we know a ‘charming’ pro-lynching fraternity chant would be going viral literally hours after Deonte delivered his paper on community building and affirmation BGLOs work through at historically predominantly white institutions. WHO KNEW!?!? Rose Boomsma (UCLA) also put a new twist on well worn music appropriation narratives with her paper “The New Age Pastime: Appropriating the Native American Flute.”

The conference was also the place to be to get a sneak preview of books in progress by our favorites in black music scholarship such as Tammy Kernodle (Miami University at Ohio) and her on timely analysis and exploration of racialized sounds during the soul era in “Be Real Black for Me’: Roberta Flack, the Quest for Artistry, and the Shifting Context of Blackness in ‘70s Popular Music.” All I have to say is GET YOUR PRE-ORDER BOOK MONEY READY because when this one drops, you gone probably be telling your grandkids where you were when you first read it. Dr. Tammy is bringing THE HEAT.

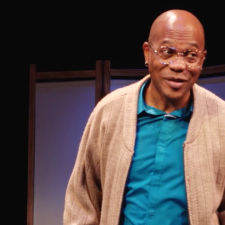

This year’s conference also saw the honoring of two pillars and pioneering black music scholars and educators who are very much still active as leaders and role models in the field of American music studies. On March 6th composer and scholar Olly Wilson was the 2015 recipient of the SAM Honorary Member Award, which recognizes scholars for their contributions and grants them lifetime membership to the organization. An appropriate biography listing all of Wilson’s accolades would fill the conference program but his early writings on the relationship between African American music and West African music were among the first by a black music scholar who was actually black, a musician, and a scholar as it had not been the case for several decades into the 20th century. In his acceptance speech, the St. Louis native noted that his pursuit of music began via a wish born of his father, who had an excellent singing voice in church, and wanted his son to pursue music because he didn’t have the opportunity to do so. So from piano at age seven playing in church, playing piano and bass at the famed Sumner High School, and his first twelve-tone composition exercise that got the attention of his music theory professor at Washington University, Wilson and his music have more than answered a black father’s prayer for his son in America after the second World War. The induction ceremony was concluded with one of Wilson’s pieces from 1977, Piano Trio, performed by The Delphi Trio. Wilson was more than gracious to all who wanted to catch a moment with him and his wife of over fifty years, Elouise. On our way to lunch, Wilson was excitedly telling me about the new Duke Ellington reader he has contributed to along with other scholars. Seventy seven is not trying to hear any parts of slowing down Dr. Wilson. Not at all!!

It was at the conference’s annual business meeting where another standard bearer of black music scholarship was honored. If Eileen Southern is the Mother of Black music scholarship, Josephine R.B. Wright is its younger and just as tenacious auntie. This year the College of Wooster professor, scholar, editor, and educator was awarded the SAM Lifetime Achievement Award for service to the society. In addition to taking the baton of Southern’s and Samuel Floyd’s road mapping of African American music, Wright cut pathways as an editor for the journal American Music as well as co-editing the book that would eventually evolve into The Music of Black Americans: A History aka the Bible of African American music history. Her impact stretches beyond music scholarship and teaching and reaches the fields of Black and Africana studies. She’s a kind of foremother for many of us professors of black music who find ourselves fortunate enough to also teach and do research in black and Africana studies on the university level full-time. She is the holder of the first endowed chair in Black Studies at the College of Wooster, where she has been on faculty for over twenty years. And like Wilson, she is also thoroughly adept at Western music and music history as her tenure in the American Musicological Society would also attest. Wright’s award was not pre-announced so the Society’s delight during Judith Tick’s announcement of the award could not be denied along with the extra seconds of standing ovation time Wright received from the entire organization packing the large ballroom. It was a great way to end the business meeting, which was masterfully time efficient and moved along like a dance led by outgoing SAM president, Judy Tsou (University of Washington) and her team.

One thing is for certain, if you want to experience some of the highest levels of musical cross-roads, academic conferences may be the best kept secret in America. The last time I attended SAM, I got to meet Clyde Stubberfield and Bootsy Collins who were on an open session panel. This year the people who literally wrote the books that ground what we know and (should) think about black music and music of the African diaspora were being heralded by their contemporaries and the countless others they opened doors for in the study of all American music by all Americans.

Tags: academia, conferences, Olly Wilson, scholarly, society of american music, tammy kernodle

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It