I, Patriarch

(or So Long, Cliff and Claire)

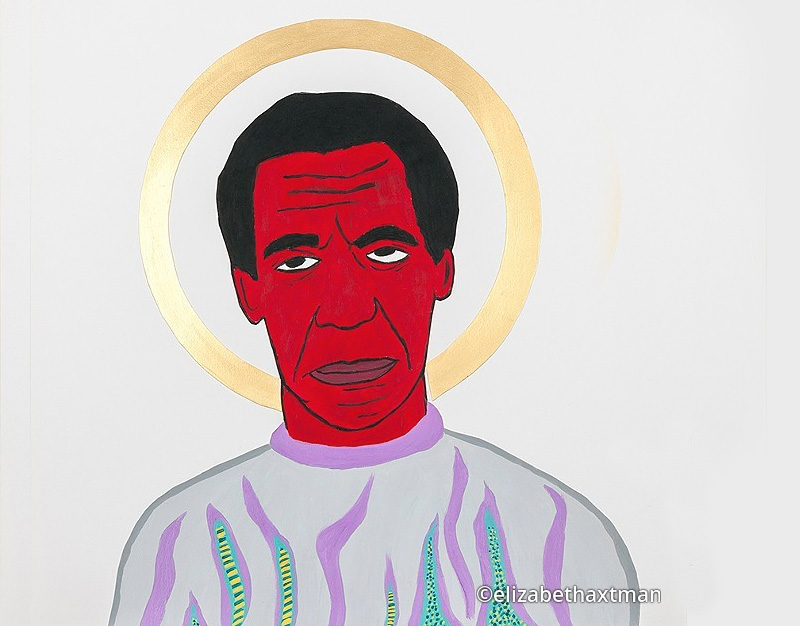

Editor’s note: The artwork is in this post is used by the generous permission of artist, Elizabeth Axtman. Please learn more about her and visit her work at ElizabethAxtman.com.

I’ve been struggling watching Bill Cosby’s reputation get lampooned from afar, particularly in the crosshairs of a cultural criticism that uses the study of mass media “representation” to achieve various forms of insurgent activist ends. Remember when this was true of all cultural criticism? As a result, we’ve witnessed some pretty intense debates recently on whether we should value or trash our memories of the fictitious Huxtables, our six-figure earning, urban and urbane two-parent, first family from the land of situation comedies. They were so cute: sort of like the Waltons from the 1970s, but with more disposable income, better jokes and musical tastes. I’m old enough to remember brother Bill from his 1960s show I-Spy, a program that because of its moment, one could only view as science fiction. A black guy and a white guy buddy drama? Really? Yeah, right. I guess there was some kind of subliminal message being projected to us hood babies through I-Spy and Julia, the show that featured Dianne Carol in the first televised show in which a black woman wasn’t somebody’s maid. I remember these shows being intriguing but, honestly, to me so was the Jetsons’ flying car, the sheer hugeness of a Flintstones’ birthday cake and the very idea of Space Ghost. Yup, that’s how old I am.

I say I’m struggling but not because America’s pudding-pushing father figure’s entire boxers are flapping in the wind with a big “kick me” sign on them. I guess this will go down in history as a classic and unfortunate example of Hyper-Sagging. Unlike some, I’m personally heartened by the way current feminist scholars and activists are consistently dissecting the structures that allow us to become totally invested in the contradictions present in the example of Mr. Cosby and others. A public art that inspired; and apparently, a private life that destroyed. We’ve seen it before, and we see it now. From bar-stool slinging gospel singers, to wife-beating iconic jazz trumpet players, to athletes who use their superior, envy-inspiring physical prowess to overwhelm those closest to them, one has to brace oneself just watching Sportscenter or logging onto your social media account.

I’m struggling because I see how difficult it must be for those activists on the front line of these debates to withstand the virulent pushback to their analyses. I also struggle because I see how difficult it is for some brothers to watch the beam by strut dismantling of familiar forms of patriarchy before their eyes. Face it, every time a brother is busted you feel implicated somehow. I do, too. And I admit this even though I was never personally any more invested in Cliff Hustable’s TV persona than I was the drug habits of the jazz musicians I was so trying to emulate. As a creator, separating the makers from the thing that was made was easy—most times. As a musician who made his living in nightclubs and churches, I witnessed the real deal. And it was beautiful and ugly and inspirational and destructive. All that.

I also struggle because, for me, black fatherhood and now grand-fatherhood is not a theoretical matter to be understood solely through scholarly analysis, dispassionate critique, bibliographic control or rhetorical craftiness. It has been defined in my life as an uphill battle, a constant life-threatening scramble for resources—emotional, physical, monetary, spiritual, cultural. Yes, I guess that makes me, dare I say it, a patriarch. I knew nothing else. It’s what I was “supposed to do.” I’ve been running for the lives of those for which I’ve pledged my honor to protect, support, inspire, collaborate and build with, love and cherish. I struggle because, I, for one, couldn’t have cared less about what Cliff was emoting on Thursday nights because I’ve always had to have at least three jobs going to keep people in soccer cleats, tutoring sessions, good schools, winter coats and warm rooms. I struggle because I suspect that not one sagger has ever bought a belt because Fat Albert’s creator implored it. Yet, I, hustle-man, could never have imagined such a bully pulpit at his disposal, one to tell the young bulls with sagging pants that I didn’t hate them, that I was trying to blaze a trail to follow, that they were me and I was them. I struggle, and although many of us guys find it hard to admit, patriarchy is never enough, never delivers what’s promised in the end. It feels like a big, fat failure. An “L” instead of a “W.” That’s why when some sharp sister with a pen and some lip chops down another one of those P-trees and yells “timber,” we cringe in concert, and in the still of the night.

I struggle because the prevalent and harmful forms of patriarchy seem to be intertwined with the father/brother/son love that we legitimately want to practice, so much so that it’s easy to be fooled into believing that a good feminist critique will make your gonads fall off. They won’t. I struggle because the sheer and necessary volume of the critique that seeks to get it right seems to drown out what post-Patriarchy might look like and feel like for those of us grinding it out as the male figure in the lives of loved ones. In the meantime, I’m on my way to a concert with my daughter, a singer. Together we’ll watch a singer’s singer work her craft. The seats are close (and expensive–ouch). But I want her—I need her—to see every breath breathed, experience every phrase sung, to hear every chord and interaction without distraction. I want her to remember the lessons when I’m gone. Yes, tis, I, Patriarch, back on the grind trying to inspire a life I helped bring in the world; and at the same time listening closely for new ways to be. We’ve really got much work to do. I guess that’s why they call it a struggle, and I’m here to admit it outloud.

Tags: bill cosby, feminism, patriarchy, the cosby show

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It