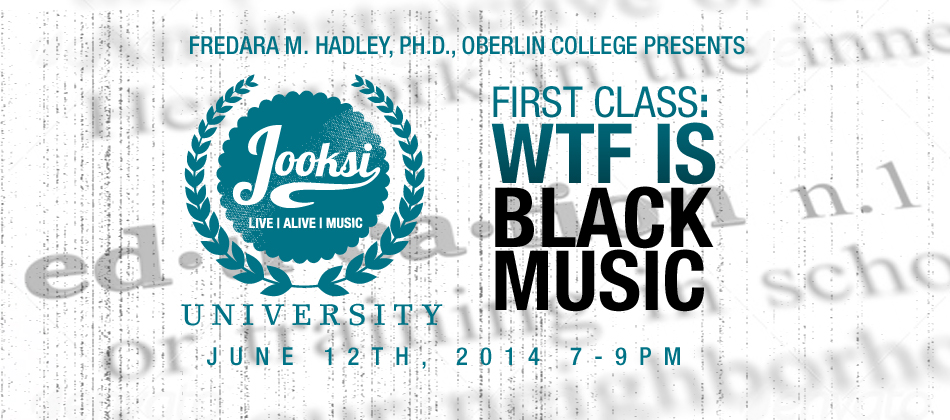

It’s a new day in black music research! One of the reasons I say this is that the field was once anchored in the academy. The scholars who researched the history and present of black music were primarily concerned with sharing the result with an academic audience through traditional channels and platforms. But a new generation is changing all of that. Dr. Fredara M. Hadley (@fredaraMareva), an ethnomusicologist trained at Indiana University and an assistant professor at Oberlin College, is in the vanguard of these efforts. That she’s also managing editor of this site, MusiQolgy.com, is not the only reason she’s a fave. Fredara brings a musical intelligence and grounding in cultural theory and participation to the table, making her insights provocative and compelling. As you can see from the links to her writing and a recent appearance on HuffPost Live, she’s an expert that can take her hard-won knowledge base and make it palatable to a wider public. We invite you to experience Dr. Hadley in action at tomorrow night at Grind Broadway as she presents her first master class: WTF is Black Music? Follow her for future classes at Jooksi.

Don’t miss this opportunity to check her out live and experience the best in the “new public musicology.”

Guthrie P. Ramsey, Ph.D.

Editor in Chief, Musiqology

Below is a piece I wrote a couple of years ago to process my feelings about Black Music Month. As we prepare for tonight’s Black Music conversation it felt appropriate to share these thoughts again.

fredara

It’s Black Music Month y’all. While I’m glad it exists, I also fight a bit of irritation about it. This year I was determined to try and figure out why.

Black Music Month and I were born within weeks of each other in 1979. It was Kenny Gamble, Ed Wright, and Dyana Williams’ idea to set aside a month dedicated to celebrating the impact of black music. (It’s notable that Black Music Month was created, not by academics, but by music business insiders who intimately understood the politics of screwy “race music” in the industry.) The group successfully lobbied President Jimmy Carter to host a reception on June 7th, 1979 to formally recognize the cultural and financial contributions of black music. Since 1979, it has grown from an obscure commemoration to full blown marketing and celebratory extravaganza.

June is now the month where cable networks trot out their Black music programming, bloggers put together specially curated collections of black music, and the White House throws a helluva Black music jam session. And while all of these things are lovely, something about it all leaves me unfulfilled. I understand that we can’t talk about Black music (or any other music) without talking about money and commerce, but the kitschy way that we present something as profound as what Amiri Baraka describes as “…music the score, the actually expressed creative orchestration, reflection of Afro-American life, our words, the libretto, to those actual lived lives.”

In remembering Amiri Baraka’s quote, I realized that Black Music Month unintentionally aggravates my frustration at the separation of black music from those “actual lived lives.” We set aside the month of June, and in that month we are bombarded with ideas of how we should “celebrate” the importance of black music, but what material impact does it have on the countless forgotten innovators who created the music that we are celebrating. As an ethnomusicologist, I am sensitive to how histories about music and people are developed, retold, and remembered. The repeated narrative of black music is that African American musicians create something, it gets redone, and becomes estranged from its African American community. It’s the crossover. It’s what allows Jay-Z to perform a FREE show at SXSW that none of his early fans can afford to attend. While the exposure and growth of a genre is a great thing because it means more people are able to get into the music. I just wish that success could carry along the music’s innovators and first supporters.

In 2000, US-Representative Chaka Fattah sponsored House Resolution 509, which formally recognized the importance of Black music on culture and the economy. Here are some particularly striking excerpts that speak to why I have a love/annoyed relationship with black music month:

Whereas African-American music has a pervasive influence

on dance, fashion, language, art, literature, cinema,

media, advertisements, and other aspects of culture;

[Read: black music is the very foundation of global pop culture]

Whereas African-American music embodies the strong presence

of, and significant contributions made by, African-

Americans in the music industry and society as a whole;

[Read: black people make black music and other stuff.]

Whereas the multibillion dollar African-American music industry

contributes greatly to the domestic and worldwide

economy;

[Read: black music makes a lot of people a helluva lot of money.]

Resolved, That the House of Representatives

(1) recognizes the importance of the contributions

of African-American music to global culture and the

positive impact of African-American music on global

commerce;

[Read: black music month is necessary because Black music is the foundation + it makes a lot of people a helluva lot of money.]

It’s this thing about global culture and profitability that leads to the separation of the music score from its people. Then when the articles, documentaries, museum exhibits are created…and the checks are written, the originators are painfully absent. This is not just a question about music history and roots, but it speaks directly to people’s beliefs about who are the people who listen to certain kinds of music. It’s like:

The crossover of R&B to rock and roll really has people (both black and white) believing that black folks do not still make and listen to rock and roll.

The museum-fication of jazz and blues has people (both black and white) thinking that black folks really don’t still create and dig jazz and blues.

The global phenomenon of house and techno has been doubly dire because lots of people (both black and white) never realized the music came from black communities in the first place so they really have no idea that there are thriving house and techno communities in and around black communities all over the world.

Let me give an illustration of what I mean. Recently my friend, Tracy, sent me a Forbes article titled “House Music Has Become a Global Phenomenon” by Dan Schwabel. An alternative reading of his title could be, “hundreds of thousands of white people in America and Europe now love house music.” Schwabel, a marketer to millennials was marveling at the meteoric rise and global appeal of house music. Before giving house music to the world, he takes two full sentences to acknowledge its roots saying, “Back in the early 1980s, Chicago club and radio DJ’s were playing various styles of dance and disco music. In the mid 1980s and 1990s, house music became a major fixation on the UK music charts.”

The more troubling part for me is the paragraph in which he lists all the house music DJs who have collaborated with top pop artists (who are coincidentally all black):

The DJ’s have taken over pop culture by producing for America’s most prominent music figure heads and by immersing themselves in clubs and at major venues. David Guetta has produced hit tracks with Akon, while Benny Benassi has worked with Chris Brown, and Calvin Harris recently collaborated with Rihanna. Electronic music was able to break into pop culture because it attached itself to popular music, creating new beats, hooks and break downs. It’s been easier for DJ’s to draw an audience because they are elaborating on music that people already enjoy. Pop culture and house music are now intertwined more than ever before and the fans are loving it.

He then goes on to interview the “World’s Greatest DJs.” The list includes people like David Guetta, Chuckie, Afrojack, Fat Boy Slim, Steve Aoki, and Swedish House Mafia. No doubt this list was compiled to specifically highlight those DJs with the strongest brand recognition with millennials.

“So what” you say? It’s just a fluff piece written by a corporate brand strategist in an out-of-touch business mag? You’re right, and that’s exactly why it matters. Far too often, pieces like this are the beginning of the new narrative of house music. The one that doesn’t know who Larry Levan, Frankie Knuckles, Ron Hardy, and Lil Louis are. The one that does not care that there are still thriving house scenes around the world in which Black people (along with other people) still dance to DJs like Lil Louis and Black Coffee.

Now contrast Forbes’ view of black music with that of the Movement Fest (formerly known as Detroit Electronic Music Festival), which turned down David Guetta’s interest in performing at the festival saying

“We feel a responsibility to utilize this festival as a chance to maintain a sense of history and heritage about the music itself,” says James Canning, media director for Paxahau, promoters of Movement since 2006. “We think [contemporary mainstream EDM] is a tremendous thing for the music scene in general as it relates to electronic dance music, techno and so forth and it’s a great opportunity to expose a broader audience to music so many people have known for so long. Here in Detroit, people like Carl Craig, Kevin Saunderson, Derrick May have been doing this for 30 years… We see ourselves as stewards of this music. ” (Taken from this Billboard article)

All of whom are black and without whom there would be nothing for Dan Schawbel to write. But my even bigger point is that May, Saunderson, Atkins, and the rest of the Detroit pioneers are NOT relics. There are still creating and performing amazing music in front of thousands of people on a regular basis.

So maybe this is where I land. Black Music Month leaves me unsatisfied because my ultimate wish is that it were not necessary at all. In other words, I wish there were no knowledge deficit to try to fill. I wish that Derrick May, Juan Atkins, and Kevin Saunderson were able to achieve half of the commercial success and acclaim as the DJs listed on the Forbes list. I wish that “crossover” meant that the artist’s whole self, music, and community had expanded its borders rather than her music serving as the oft forgotten inspiration for the success of others.

Tags: African American Music, Black Music, ethnomusicologist, ethnomusicology, fredara m. hadley, Indiana University, Jooksi, music, new york city

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[Video] BBC Documentary on Allen Toussaint](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/allen-toussaint-225x225.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Black Music and the Aesthetics of Protest](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/onlynchings1-225x225.jpg)