Together with my course “Jazz Speaks for Life,” I’m also teaching “The Big Sea: An Introduction to Africana Studies.”

This course provides an introduction to the field of Africana Studies and what has marked its distinctive and continuous development as a discipline separate from, but inextricably linked to, African or African American Studies. We will address a number of questions that have proved to be of fundamental importance throughout the history of the study of the African Diaspora.

The materials in this course include literary, social science, historical, and expressive culture fields. Because the literature of Africana Studies is vast, interdisciplinary, and varied, we have chosen works that will provide you with a clear, though not exhaustive, understanding of core questions and themes of the discipline.

This course will explore the relationships among subject matter, methodology, and our (including yours) responses to each of these realms. We are as much interested in understanding the core issues at stake each week as we are committed to interrogating the manner in which a topic has been engaged by the various scholars and writers included in the reading list. In other words, we will throughout the semester try to understand the development of something called “Africana Studies,” but will also try to understand the historical and material conditions in which writers, scholars, cultural critics, musicians, filmmakers, and visual artists, among others, have engaged and executed their chosen materials.

Throughout the course we will approach the “text” (literary, statistical, artistic, etc.) under consideration as not just a conveyor of objective “facts” or as an expression of “pure” unmediated aesthetics. We treat them, rather, as rich discourses tied to specific subjectivities, historical moments, methodological stances, and geographical locations that achieve important cultural work in the social world.

We will read the following books in their entirety together with other articles, essays, and briefs.

Mark Anthony Neal, Looking for LeRoy: Illegible Black Masculinities

Farah Griffin, If You Can’t Be Free, Be A Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday

Imani Perry, More Beautiful and More Terrible: The Embrace of Racial Inequality in the United States

Guthrie Ramsey, The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History and the Challenge of Bebop

Ayana Mathis, The Twelve Tribes of Hattie

Sharon Patton, African American Art

Kevin Young, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness

Lucille Clifton, The Selected Poems of Lucille Clifton

Along with these readings the course takes serious expressive culture as a realm in which to engage issues in Africana Studies. We will attend the film by black British filmmaker Steve McQueen, Twelve Years a Slave, which happens to debut this semester. We will also attend three art exhibitions: “The Shadows Took Shape: Afrofuturism” (Studio Museum in Harlem, Nov. 14-March 9); “Barbara Chase-Riboud: The Malcolm X Steles” (Philadelphia Museum-10/14-1/20); “Rising Up: Hale Woodruff Murals at Talladega College” (July 20-October 13, NYU). Finally, we’ll attend three live concerts: Gary Burton, Joshua Redman (both at the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts), and Bobby McFerrin at Kimmel Center, Philadelphia.

~~~~~

During the two weeks we will discuss the following broad issues that will guide us throughout the semester. The first one is obvious: “What is Africana Studies?” The next takes up an issue posed by W.E.B. DuBois’ powerful book The World and Africa, “What has been the historical relationship of Africa to world affairs, broadly speaking?” How can we talk productively about the relationship between structural inequality and diverse acts of resistance (i.e., cultural politics and formal political action) without falling into well-rehearsed stereotypes about governments, ruling classes, and people who are the targets of hideous social arrangements designed to keep them “down.” How have people of African descent used various forms of expressive culture—music, art, literature, and photography—to create beauty through multi-faceted aesthetics that provided confrontational self-worth and their humanity?

The following readings framed our journey:

Elliot P. Skinner, “Transcending Traditions: African, African-American and African Diaspora Studies in the 21st Century — The Past Must Be The Prologue.” The Black Scholar, Fall/Winter 2000, Vol. 30 Issue 3/4, 4-8.

Imani Perry, More Beautiful and More Terrible, 1-42

W.E.B. DuBois. The World and Africa. 1-80

Langston Hughes. The Big Sea, Parts 1 and 2

Phillis Wheatley, “On Being Brought from Africa to America” (1773) poem

Sharon Patton, African American Art, Chapter 1

Skinner’s work is a brief historiographic overview of what he sees as key texts and themes in Africana thought through the lens of “resistance.” He covers various ideological shifts through historical texts and cultural forms. A central idea here is how Africa, Africans, and the idea of Diaspora were “made” from both sides of the color line. He charts how the fields of science, and even anthropology, circulated theories of inferiority and how such theories informed systemic political, military and economic control. Yet in the face of this, Skinner writes, there were always acts of resistance from many arenas. Phillis Wheatley’s poems, Benjamin Banneker’s scientific inquiry, DuBois’s paradigm shifting use of sociological praxis, CLR James’ account of the Haitian slave revolt, the founding of Liberia, and the establishment of international conferences that addressed Pan African concerns. Other instances of formal and cultural politics, according to Skinner, include: the Francophone Negritude movement, the so-called Harlem Renaissance, and the establishment of anthropological practices that studied how cultural survivalism, syncretism, and creolization theories could be used to frame the notion of New World black cultures as viable and reasonable. Skinner asserts (after DuBois) that Africa—despite hideous ideas about it being outside of historical narratives of the West—has been a key player in world affairs.

After the overview, the first two chapters in Imani Perry’s study, More Beautiful and More Terrible, provide our course with a theoretical framework for understanding the social energies that circulate between ideological structures in a society and the lived experiences of people participating in them. In a book that deals with “the application of cultural studies analysis to social science research,” Perry pursues two questions: “How does a nation that proclaims racial equality create people who act in ways that sustain racial equality?” And, she asks, “What can we do about it?” She builds a framework to understand structural and individual discrimination, not as personal intention, but as a powerful all-American cultural practice sustained by institutional bias. The book allows us to move beyond “feelings” and personal slights (often the focus of race discussions in public discourse) and focus on how cloaked structures allow a theoretically benign yet devastating consequences for society members. By doing so, Perry explains the difference between “intent” and “behavior,” a distinction that can either illuminate or stall discussions of race and the “practice of inequality,” as she calls it. Grounded in social science data, Perry explores what the research shows and how our everyday thinking about inequality remains out of step.

The usefulness of Perry’s work in this course is that it provides us with theoretical language to talk about the traffic flowing among different social orders (modernity, slavery, colonialism, segregation, and post-Civil Rights discrimination) and acts of resistance, large and small (Pan-Africanism, Negritude, Civil Rights, Black Consciousness, and Hip-Hop-era politics).

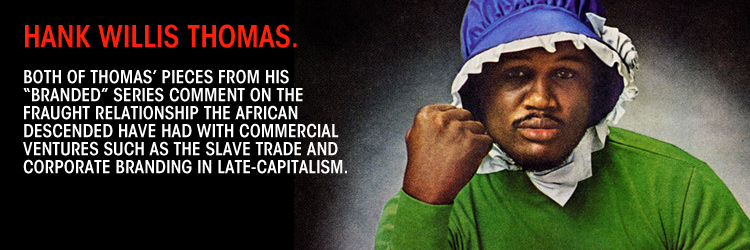

One question that comes up often is the idea of “cultural politics.” For our purposes, (following Richard Iton’s ideas in In Search of the Black Fantastic), it means taking expressive culture seriously as political intervention without confusing it with formal politics and it discourses. To illustrate this point, let’s look at three pieces of visual culture. The first two are works by artist Hank Willis Thomas. The other is a film titled Baldwin’s Nigger (1969).

Both of Thomas’ pieces from his “Branded” series, comment on the fraught relationship the African descended have had with commercial ventures such as the slave trade and corporate branding in late-capitalism.

Directed by Horace Ové, the film “Baldwin’s Nigger” presents a fascinating lecture by the writer James Baldwin with commentary by activist and comedian Dick Gregory. Taking place at the West Indian Student Centre in London, they are speaking to Caribbean people living in England about their common Pan-Africanist concerns. Beginning with his own experiences as a native New Yorker, Baldwin traverses “the Big Sea” by drawing connections among the common plights and political struggles. The question and answer session is lively and unforgettable and shows some on-the-ground politicking about social and cultural identities, integration, and power.

Next week: How is Africa represented in the works of Phillis Wheatley, W.E.B. DuBois, Langston Hughes, and the in architecture, crafts, and fine art among the first enslaved Africans in the New World?

PRE-COLONIAL MAP OF AFRICA, 1858

CARRIBEAN SEA

Tags: Africana Studies, fall semester, teaching, undergrad course

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It