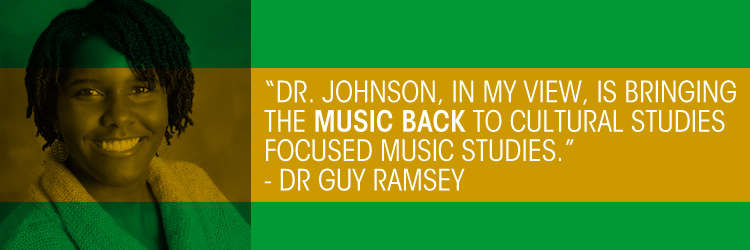

I learned about ethnomusicologist Birgitta Johnson through social media. As I read and pondered her posts, I experienced what can only be described as a force. Forget what Justin Timberlake claimed he did. Dr. Johnson, in my view, is bringing the MUSIC back to cultural studies focused music studies. She trained at UCLA with the legendary Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje (you should know this name and her work) and Cheryl Keyes, the lady who put hip-hop studies on the map in ethnomusicology back in the day. She is currently an Assistant Professor of Music at the University of South Carolina School of Music. What makes her such a rare gem? Her impressive grasp of repertoire comes from her life as a trained musician in western art music as well as in various styles of the African Diaspora. Her critical insights are drawn from a sound theoretical grounding and from what she learned through extensive research in megachurches, the focus of her current research. And somewhere along the line Professor Johnson listened to the elders because the “Motherwit” is a killer. Stir in a great sense of humor (she’s the grand mistress of the one-liner bomb that knocks you on the floor even while she’s teaching), and you understand that you’re experiencing an intelligence and wit of the highest order. What were some of her formative texts? Read below

Birgitta J. Johnson (@DrBirgittaSays) is an Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology in the School of Music and African American Studies Program at the University of South Carolina. She specializes in African American and African music, and her research interests include musical change and identity in black popular music and music and worship in African American churches. She has published articles in Black Music Research Journal, Ethnomusicology Forum, and Music Research Institute Press (MRI) and has research forthcoming in Penn State University Press. She is currently writing a book manuscript based on her ethnographic research on music, worship, local liturgies, and negotiating identities in African American megachurches and urban congregations in transition around the United States.

As an ethnomusicologist, I find that I am just as hardcore about history as I am about performance culture and cultural context(s). The books I continually go back to in my research and teaching represent the type of works that Halle Berry would be crying about if she won the Oscar for black music and culture scholarship. The ability to stand on the shoulders of the copious amounts of dates, names, places, institutions, and works as well as quantitative data presented in these two works, elevates much of the discussions around black music in the 20th century away from essentializing the mystical or becoming complacent with centralizing research around western art music models of “great men” and/or “great works.” In providing actual historical data where there was little to none previously and modeling systematic ethnographic approaches to examining music in its cultural and social contexts over large spans of time, these two works provide a guide to seeing the forest as well as celebrating the trees that root and nurture African American music culture even into the 21st century.

Eileen Southern: The Music of Black Americans: A History (1971)

Now in its third edition and compiled by Harvard University’s first tenured African American full professor, this epic work is considered the bible of African American music history. It is still a major and “go-to” resource for a large percentage of accurate and thorough knowledge of the broad musical canon that African Americans have brought to, created, remixed, and shared with this country, despite the circumstances of their arrival, and their complex and often denied status as Americans – not to mention human beings in this country. It chronicles the first musical expression of Africans brought to America as the country was being founded, all the way up to the explosion of sacred and secular forms African Americans developed and innovated to impact American music, culture, and society in the 20th Century.

Melville J. Herskovits: The Myth of the Negro Past (1941)

While much of American society and academe considered Africa “the dark continent” and enslaved African’s descendants west of the Atlantic uncivilized and incapable of having original cultural expressions and perspectives, in the 1920s and 1930s anthropologists like Melville Herskovits, Zora Neale Hurston, and others set out to systematically prove otherwise. By conducting ethnographic studies of story telling, music, social customs, commerce, and art in West Africa and all the areas where African of the so-called “New World” were held in bondage, Herskovits started a wave of myth busting about the lack of original creative genius as well as the maintenance of African cultural aesthetics and traditions among Afro-American groups in the Western hemisphere. Connecting, in some cases, direct links to their African roots, The Myth of the Negro Past described and proposed the concept African “survivals” in Afro-American cultures that proved the resiliency of African culture even in the face of The Middle Passage, several centuries of enslavement, and sometimes contested contact with Euro-American traditions. Our ability to connect hip-hop to the blues and blues to Africa today owes much to this work.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It