The following is an overview of lecture notes from my History of American music course this semester. -Editor

Her fans were delighted to see Beyoncé, The Bootylicious, our reigning queen of American pop, step to the podium and offer an anticipated rendition of the National Anthem at Barack Obama’s recent inauguration. Fresh off her revealing and seductive GQ photo shoot, she had morphed back into her “role model for youth” persona: conservatively dressed, figuratively wrapped in Old Glory, and ready to lead the nation in song. With gay Latino poet – Richard Blanco, Kelly Clarkson (of American Idol fame), James Taylor’s folksy baby boomer crooning and the demographically integrated, inner-city Brooklyn Tabernacle Choir blasting anthems in bel canto voice, it was difficult to not be drawn into the celebration with such an “all-American” line up.

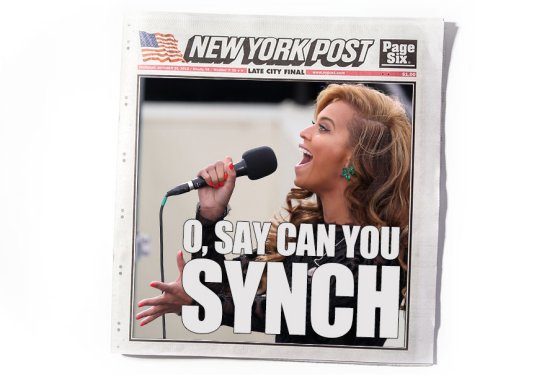

Posts on my Facebook and Twitter accounts raved as the crowd roared its approval. When it was “leaked” that Queen B may have lip-synced her performance the news almost upstaged everything that was going on in D.C.—even Hilary Clinton’s recent congressional testimony on Benghazi. Divas J-Lo and Aretha Franklin weighed in on the “controversy.” Clearly, many believed that some kind of social contract had been breached. The combination of God, country and pageantry demanded a vocal performance that lived up to these lofty ideals.

The entire scenario and its fallout highlight some ongoing themes that have been a stable feature of the continual diversification of American musical culture since its inception. And certainly among all of these issues, the search for “authenticity” has been, arguably, one of the driving social forces shaping the American musical landscape. As we learn in Richard Crawford’s text, An Introduction to America’s Music, the first three centuries of American music was a history in which various political, cultural, economic, and social interests intersected in sonic form. If we take our governing question, “Why are these people making this music at this time in this place?”—a mantra from musicologist Christopher Small—as a guide, we can discipline these social energies into manageable clusters of ideas. The melting pot character of American culture makes the search for an American authentic an elusive pursuit, one that nonetheless has kept musicians and audiences hopping—and guessing.

Identity, and its politics, have been central to the processes of nation building and by extension, the establishment of “an” American music culture. The large groups in the story at this point—European settlers, Native Americans, African Americans and their descendants—all contributed to the musical landscape in rich ways. Although each group and their sub-sets were bounded by social norms that claimed limited engagement with each other, music history shows us that inter-musical transactions were abundant. Indian music was represented in print by 1670, although transcribers readily admit that they couldn’t come close to how it actually sounded. In other words, their transcriptions weren’t “authentic.” African American music in both its secular and sacred articulations swept through colonial America with force and religious fervor despite the social standing of its creators. And European-derived music in all of its richness and variety provided a platform to establish the beginnings of the American culture industry, as enterprising musicians dreamed up ways to muse on politics, the birds and the bees, God, and country—and mostly with a reasonable price tag.

Ethnomusicologist Frances Densmore recording Blackfoot Chief, Mountain Chief (1916).

American institutions such as singing schools, home parlors, the military, and the early theaters provided alternative cultural spaces to churches for “musicking” (music and all its attendant activities) as the population became more diverse in its tastes and more eclectic in its desires. And thus, we see in this historical setting other kinds of social collectives emerge, ones not based solely on race or ethnicity. This process will continue through the years, as we shall see.

Yet the early American church in all of its iterations was a core institutional base for musicians. The first full-length book to be printed in the English-speaking colonies was the Bay Psalm Book in 1640, affirming the importance of religion and music for the early Americans. Debates among parishioners about the value of choirs—rehearsing specialists—versus lay members’ singing their untalented hearts out were among the first American discussions about aesthetics. The importance that various strains of Christianity placed on either the “artfulness” of praising God (edification) or the praise and accessibility of the average congregant laid the groundwork for the establishment of the “art sphere” of and the sacredness of its overtones that would develop throughout the 19th century. The idea of authenticity was used to shape both sides of this argument. When African American musical practices became part of the fabric of American music it not only set the nation’s aesthetics in another direction, it changed the idea of American authenticity. (And not to mention eventually what would be an accepted rendition of the national anthem!) As new “folk,” like the Irish, immigrated to these shores, our national “sound” would absorb these identities into the melting pot, first as novelty and then as acceptable rhetoric.

When Francis Hopkinson of Philadelphia, an amateur musician, wrote “My Days Have Been So Wondrous Free” (1759)—the perfect parlor piece—it became the first known secular song by a native-born American. Written in the tradition to “the British song tradition,” it would take nearly a century before American popular music would become truly indigenous. We should remember that through the black church, the performance of American secular song would never be the same: indeed, it would be the thing that helped to contribute to our nation’s musical outlook moving away from its early European influence. The military bands were an important avenue for American instrumental music—both functional for the troops and eventually and aesthetically crafted for audiences’ listening pleasure. Wind bands, of course, became the template for the jazz ensemble. Although concert and theater life were British knock-offs when minstrelsy emerged, a truly American form of entertainment was born.

If we recognize three primary revenue streams in music today—live music making, publication, and recording—then clearly two of these are in place before the dawn of the 19th century. Important questions to consider in our journey will be: How do these streams influence one another? How will they develop in the future? And how will they change when recording enters the mix?

When audiences and journalists debate the “validity” of Beyoncé’s inauguration performance, they are participating in a very American ideal of what it means to represent an authentic “self” to the public through musical practice. American music history shows us that these aesthetic discussions have been going on since the 17th century. Within these artistic discussions are very strong notions about who we believe we are as a nation of listeners. Music has always mattered to us.

Tags: beyoncé, Black Music, inauguration, Music History, musicking

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[Video] BBC Documentary on Allen Toussaint](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/allen-toussaint-225x225.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Black Music and the Aesthetics of Protest](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/onlynchings1-225x225.jpg)