Guest Blog by Steven Nelson

“Now Dig This! Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980” is open until March 11, 2013 at Moma PS1.

From a petition/open letter signed by over 1,500 people, including leading artists, curators, and art historians, to heated discussion on Facebook, there has been a maelstrom of controversy surrounding Ken Johnson’s October 25th New York Times review of “Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960-1980,” currently on view at MoMA PS1. While we can argue (and disparage) the critic’s politics, what I find troubling in the essay as well as in the majority of criticism it has engendered is the inattention given to the exhibition itself. Most disturbing, however, is the Times’ editors refusal to publically acknowledge any criticism of the review. (I submitted an earlier version of this essay to Times editors on several occasions. Only one, Jonathan Landman, Culture Editor, responded, intimating that publishing this text in the pages of the newspaper isn’t under his purview.) Both Mr. Johnson and the Times have done readers a terrible disservice.

“Now Dig This!” provides an extraordinary overview of black art and institutions in Southern California during a time of social upheaval and the postwar ascendance of Los Angeles as a major art center. Instead of giving information on the exhibition or engaging its actual curatorial concerns, Mr. Johnson’s essay obsesses on the origins of assemblage and opines on the limited appeal of most of the artwork. The critic’s detractors share the mania.

“Now Dig This!,” organized by the Hammer Museum and curated by Columbia University art historian Kellie Jones, was part of the 2011 Getty Foundation initiative “Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945-1980.” Springing from Dr. Jones’ longstanding research on postwar black art in Los Angeles, “Now Dig This,” includes some 140 works by 32 artists, charts the contributions of African American artists and histories of the institutions that supported them. The exhibition also highlights the critical importance of Los Angeles as a hub for black artists at this time, dispelling the notion that the only notable centers of black art production were New York and Chicago.

David Hammons, “America the Beautiful,” 1968. Lithograph and body print. 39 x 29 1/2 in. (99.1 x 74.9cm). Collection of the Oakland Museum of California, The Oakland Museum Founders Fund.

More than a segregated view of the black art scene in Los Angeles, “Now Dig This!” explores connections between African American artists, other artists of color, and the local artworld-at-large. The exhibition makes it clear that an African American art history of Los Angeles cannot be fully articulated without understanding its larger context.

“Now Dig This!” highlights a stunning array of artwork, including Charles Whites’ large-scale drawings of the 1960s; Melvin Edwards’ assemblages, collectively called “Lynch Fragments;” Suzanne Jackson’s lyrical paintings; David Hammons’ body prints; Maren Hassinger’s galvanized steel sculpture; and Fred Eversley’s Finish Fetish minimalism, to name a few. Moreover, such wide variety explodes preconceived notions about the kinds of artwork that black people made during the postwar period.

How did Mr. Johnson miss all of this?

The answer lies in what the critic sees as the exhibition’s paradox: “Black artists did not invent assemblage.” Given that the curator makes no such argument about the exhibition, Mr. Johnson’s accusation is irrelevant to understanding the evocative power of assemblage in the show. Far from a simple misinterpretation of the exhibition’s curatorial goals, however, Mr. Johnson’s comment, which he has since called “imprecise” and “needlessly provocative,” is nevertheless deployed to devalue the work on display. Black artists indeed appropriated assemblage, and they used it, sometimes brilliantly, for their own agendas. For Mr. Johnson, such appropriation fails because African American artists did not use the medium as an apolitical tool, and, to use his own words, as a “playful messing with habitual ways of thinking….”

Suzanne Jackson, “Apparitional Visitations,” 1973. Acrylic wash on canvas. 54 x 72 in. (137.2 x 182.9 cm). Collection of Vaugh C. Payne Jr., M.D.

Yet Mr. Johnson’s assertion about assemblage’s apolitical nature in the hands of white artists is grossly overstated and, at times, simply incorrect. White artist Ed Kienholz’s assemblage “Five Car Stud” (1969-1972), an intense meditation on white hatred of blacks, is an overtly political affair, and it was considered so controversial that it was never shown in the United States until the Los Angeles County Museum of Art resurrected it in 2011 as part of “Pacific Standard Time” (it was on view at the same time as “Now Dig This!”).

With his singular attention on assemblage, which, as Los Angeles Times art critic Christopher Knight notes, populates about one-third of “Now Dig This!,” Mr. Johnson ignored the majority of artwork in the exhibition.

Mr. Johnson’s take on the politics of black assemblage, which in his mind constitutes for the most part an “art of black solidarity,” feeds into his reasoning for the lack of acceptance of African American artists in the upper echelons of the mainstream artworld and for what he sees as the art’s lack of appeal to a broad audience. The critic conflated articulations of a politics of oppression with calls for black solidarity (the two are not synonymous). Some of the work does indeed act as a call to action; most of it does not.

Concerning audience interest in the work, Mr. Johnson’s assertion of its limited appeal is belied by the exhibition’s very appearance at MoMA PS1. “Now Dig This!”, according to the Los Angeles Times, was the seventh highest attended of “Pacific Standard Time’s” 69 exhibitions. It is the only one to travel to New York.

At the end of the day, Mr. Johnson’s review revealed far more about his own politics and preconceptions of black art than it did about “Now Dig This!” You don’t have to be black to see that.

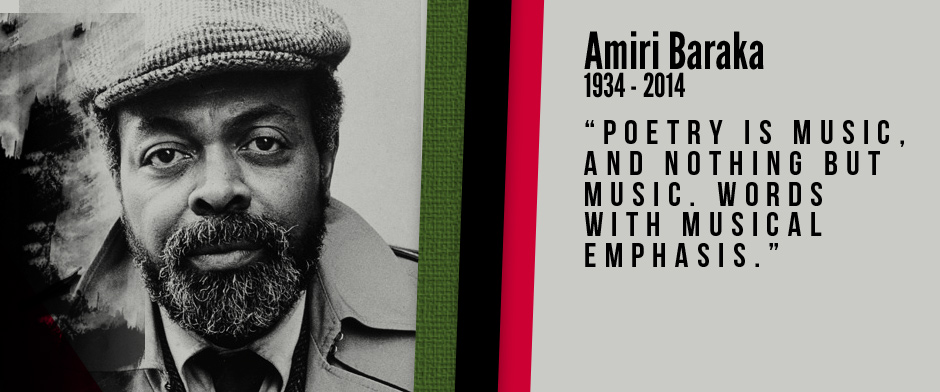

Editor’s note: Watch Kellie Jones’ December 2011, Hammer Museum talk with her father, poet and activist Amiri Baraka, here.

Steven Nelson is Associate Professor of African and African American Art History at the University of California, Los Angeles

Tags: Amiri Baraka, black art, Charles White, David Hammons, Fred Eversley, Kellie Jones, ken johnson, Los Angeles art, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Maren Hassinger, Melvin Edwards, MoMA PS1, New York Times, Now Dig This, Pacific Standard Time, Steven Nelson, Suzanne Jackson, The Hammer Museum

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[Video] Greg Tate Delivers Timely Keynote Address at SEM](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/gregtate-225x225.jpg)