The accelerated production of visual art, literature, and music that characterized the “Harlem Renaissance” during the 1920s and beyond raised rich, contemporaneous questions about black cultural politics on many levels. Among them: what did it mean to be a black artist; what was black artistry; and who were black people in the context of international, global networks of oppression and creativity? And, of course, where was the money in this so-called New Negro world?

Art, politics, and commerce, indeed, collided dramatically in this fertile setting. W.E.B. DuBois, a key public intellectual at this time, knew that art could move things whether it was intended to or not. In his writing from 1897, “The Strivings of the Negro People,” DuBois insisted that music, in particular, was a registration of the “souls of black folk” and could serve as a tool in the struggle for social equality. Building on the work of the early collectors of African American culture such as Slave Songs of the United States (1867) and on the performance work groups like the Fisk Jubilee Singers, DuBois believed that the spirituals—particularly those set in modernist dress–could function in this capacity. While he considered other popular music of the time (i.e. the hugely popular “coon songs”) derisions, DuBois believed that the spirituals harnessed a usable past and a powerful present—particularly when performed within the decorous “high-art” culture of western art music. The musicians, then, would become “co-workers in the kingdom of culture” together with white Americans with similar goals of uplift for the Negro. According to historian David Suisman, DuBois felt so strongly about the role of culture in the struggle that he mentioned the ill-fated and black-owned record label Black Swan in London during his official remarks at the Pan-African Congress of 1923, which had convened to address pressing issues of the African Diaspora. (It’s important to remember here that even the idea of Diaspora at this time represented a process of self-conscious construction based on shared politics of oppression).

Convening of the 1919 Pan-African Congress highlighting the grievances from various nations against European and Western oppressors

As we cut deeper into New Negro aesthetics and politics one sees not a unified movement but a richly contested era of goals, outcomes, identities, diverse priorities, production values and aesthetic conventions. Jazz and other forms of popular music had to be gradually embraced by elites as a platform for black social equity. Thus, by the 1970s when jazz was anointed “America’s classical music,” it had been transformed aesthetically, politically, and in social pedigree. Poet Langston Hughes was apparently prescient when he wrote the following in a 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”: “Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near-intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand.” Hughes’ essay was, of course, a response to writer George Schuyler’s claim in “The Negro-Art Hokum” that there were no real aesthetic (and thereby socio-political) distinctions among the art made by African Americans and others. This debate continues. What is more, A.B. Christa Schwartz and many other researchers have argued that queer and open sexualities were a given in the cultural space of Harlem at this time. Together with the idea that white patronage also defined the moment all supports the struggle between racial uplift and the aesthetics of “git down” were just some of the complexities running through the Renaissance. And, of course, the money trail always reveals who might be pulling the strings and guiding artistic choices behind the scenes.

The combination of commercial markets, individual innovations, and communal sensibilities continued to produce a rich variety of musical forms beyond the concert stage from the 1890s onward. Circulating through written and oral means of dissemination and gathering stylistic coherence gradually over time, the ragtime, blues, and early gospel music can all be considered products of eclectic heritages and performance practices. Each would prove to be foundational to many forms of twentieth century music making. Between World War I and II, jazz, for example, grew from a localized phenomenon and into an internationally known genre.

By the 1920s New York had become the center of the music industry, drawing black musicians to its numerous cabarets, dance halls, nightclubs, and recording opportunities; its lively community of musicians forged new ideas that would attract worldwide attention. Musicians such as bandleaders James Reese Europe (1881-1919), composer and arranger Will Vodery (1885-1951), and William C. Handy (1873-1958), together with many others, had laid the foundation in the preceding decade for the sharp, subsequent demand for black entertainment. Many of the most influential musicians moved between activities in the black theater and the creation of syncopated music for large orchestras that became America’s dance soundtrack. Improvising ragtime pianists such as Eubie Blake, Jelly Roll Morton, Willie “the Lion” Smith, Luckey Roberts, and James P. Johnson wrote and performed piano dance music that became foundational to what would be known as the “Jazz Age.” Although they have been up until recently largely written out of this history, female musicians such as Hallie Anderson (1885-1927) and Marie Lucas (1880s-1947) were abundantly present on the scene.

Jelly Roll Morton

Musicians on both sides of America’s racial divide— Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Bix Beiderbecke, Benny Goodman, Mary Lou Williams, and many others—became well known jazz figures, and in some cases, true icons. Ellington’s career, in particular, was symbolic of jazz’s ascendance on many levels. His idiosyncratic approach to composition, arranging, and orchestration demonstrated the artistic potential of popular music, a trail blazed earlier by pianist and composer Jelly Roll Morton. The impact of jazz could be measured not only in record sales—it would become by the late 1930s America’s popular music choice—but also by its emergent (and international) written criticism, which over time, bloomed from discographical surveys for collectors to record reviews, robust essays, and later, book-length studies.

With the rise of modernism in the United States, black music, particularly in the hands of black musicians, became a point of debate and speculation. Its value in the public sphere took on a variety of non mutually exclusive configurations which included: an expression of cultural nationalism; an avenue for commercial gain; propaganda in the fight for equal rights; and a variety of other ideas imposed by record companies, critics, “slumming” white audiences, and black intellectuals. Similarly to other expressive arts—film, photography, and literature— during the 1920s and 1930s, black music informed and was influenced by large, sometimes incongruent, cultural movements such as primitivism, the Harlem Renaissance, and Negritude. This, together with the overwhelming popularity of popular dances like the cakewalk, the Charleston, the Jitterbug and the Lindy Hop—all of which became international sensations— worked to saturate the sensibilities of black popular music into all sectors of global society—in mind, body, and spirit.

Like they had in other realms of black music, the concert music culture among Harlem Renaissance musicians had begun to take root prior to the Renaissance years. Musical activities among concert musicians during this period moved in two directions: attempts to break the color line in the established art world and numerous acts of institution building among African Americans for their own constituents. Black singers and instrumentalists continued to make inroads through their artistic endeavors by touring and concertizing in prestigious venues throughout America, the West Indies, and Europe. Emma Azalia Hackley (1867-1922), R. Nathaniel Dett, Carl Diton (1886-1962), Hazel Harrison (1883-1969), and Helen Hagan (1891-1964) were among the pioneers who toured extensively and built careers of which both the black and white press took notice. Although their careers were progressive in many ways, these artists met many obstacles because of the racial climate. As such, together with teaching at historically black colleges, they began to build their own institutions—concert series, music schools and studios, opera companies, chorale societies, symphonies—that perpetuated the performance and study of art music in African American communities.

In the concert world, other ideas about musical modernism beyond the jazz revolution were taking shape. The establishment of first-rate schools of music in America; the growth of urban, in-residence symphony orchestras and opera companies; and a new avant-garde musical language that turned away from diatonicism, all created a larger chasm between art and popular realms. Some black performers with designs on concert careers responded by specializing in art music and by dabbling less in the popular arena as in years past. Some continued to make a living in both realms. From 1921, when Eubie Blake’s and Noble Sissle’s production Shuffle Along premiered, black musical theater produced an aesthetic middle ground as its conventions embodied a mixture of popular song, blues, ballads, choral number, expert arrangements and symphonic orchestrations. Duke Ellington’s Symphony in Black: A Rhapsody of Negro Life (1935) extended this musical language of entertainment that was shared by composers across racial lines.

The National Association of Negro Musicians, chartered in 1919, has up to the present, provided a haven of institutional support for black performers, teachers, and composers whose work remained primarily situated in the art world. Singers Roland Hayes, Marian Anderson, Paul Robeson, and Dorothy Maynor built careers that took them to concert stages around the world in recitals, opera companies, and before symphony orchestras. They developed a large following among black audiences and therefore developed repertory that featured art songs based on black thematic materials. The Negro String Quartet, the National Negro Opera Company, the Negro Symphony Orchestra, and professional choruses formed by Hall Johnson and Eva Jessye continued the legacy of institution building among musicians who continued to face varying degrees of discrimination in the concert world. In 1935 Jessye was appointed the choral director for Gershwin’s iconic opera Porgy and Bess, a work that would become a major platform for black opera singers for decades to come. Dubbed “An American Folk Opera,” the opera’s embodiment of the spirit of black vernacular music, evocations based on Gershwin’s research in South Carolinian black communities, could be interpreted in the legacy of the black cultural nationalism espoused by earlier composers.

The 1930s saw the emergence of full-fledged symphonic works based on thematic material derived from black culture. William Grant Still’s Afro-American Symphony premiered in 1931 and made history as the first work of its kind by a black composer to be played by a major symphony orchestra, the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra. Still’s prolific output spanned opera, popular music, orchestral work, film and television work and chamber works, all contributing to his designation as “Dean of Afro-American composers.” Florence Price (1888-1953), one of the few female composers at this time to find acclaim, wrote pedagogical pieces, radio commercials, and serious concert works, including the Piano Concerto in One Movement and Symphony in E minor (1932). Many of the pieces written by black composers during this time expressed what might be called an “Afro-Romanticism”—works that used black thematic materials couched in the language of 19th century Romanticism. William Levi Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony, which premiered in 1934 with The Philadelphia Orchestra, was such a work. Shirley Graham, the versatile and dynamic musician who later married W.E.B. DuBois, composed and wrote the libretto for Tom-Tom (1932), an opera in three acts that made history as the first of its kind by an African American woman.

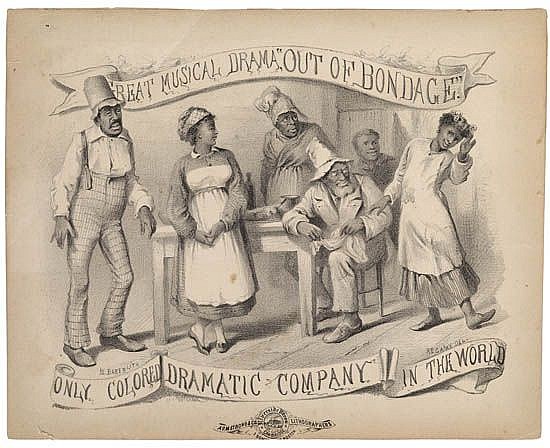

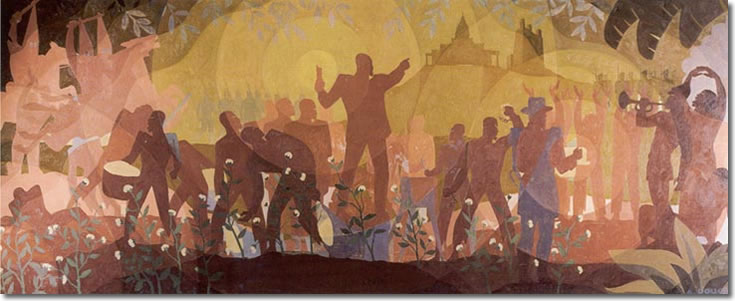

The visual art world saw equally compelling work designed to push Afrological sensibilities into the larger arts scene. Sculptor Meta Warrick Fuller’s (1877-1968) “Ethiopia,” circa 1921, also known as “Awakening Ethiopia,” “Ethiopia Awakening” or “Awakening of Ethiopia” was commissioned by DuBois for the America’s Making Exposition (Colored Section). It is the image of a pseudo-Egyptian woman unwrapping her swathed lower body, a metaphor of self-emancipation. The work obviously conflates interest in historical Egypt with mythical representations of Ethiopia, which some African Americans used to describe Africa writ large. Another artist Aaron Douglas painted a series of murals for The New York Public Library at its 135th Street branch (the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). The four panels Aspects of Negro Life highlight Douglas’s style: “graphically incisive motifs and the dynamic incorporation of such influences as African sculpture, jazz music, dance, and abstract geometric forms.” Indeed, visual culture’s obsession with “a black past” and its investments in modernism make it the perfect analogue for musical practice in the Harlem Renaissance.

New Negro art, music and literature, it seems, not only served as propaganda for Renaissance goals, it also was repository for artists to struggle with identity politics and aesthetic experimentation.

Tags: Black Music, Blues, Classical Music, Harlem Renaissance, James Reese Europe, Jazz, Langston Hughes, National Association of Negro Musicians, new negro, New York, Ragtime, The Fisk Jubilee Singers, W.E.B. DuBois

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[Video] BBC Documentary on Allen Toussaint](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/allen-toussaint-225x225.jpg)

![[VIDEO] Black Music and the Aesthetics of Protest](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/onlynchings1-225x225.jpg)