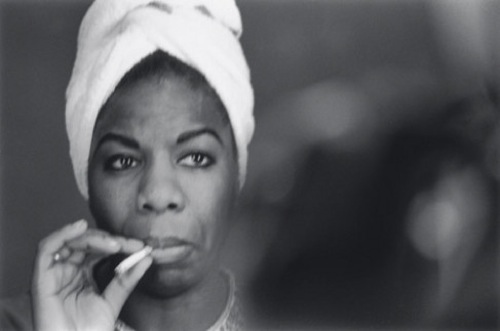

Black Music Month, Day 8

Nina Simone’s performance of the spiritual “Nobody’s Fault But Mine” enjoys several aesthetic and ideological tributaries that contribute to its power, its riveting grip on listeners (check out the youtube comments). Simone’s alto voice combines with her own piano accompaniment to convey an emotional arch that doesn’t ebb and flow but remains placid until the build up and climax during the last refrain and tag.

The subtle techniques she uses to achieve this are discussed below. Equally compelling, though, are the ideological streams flowing and give life. The song channels, in my view, an African American art song tradition and the Pentecostal “church song.”

Although black Pentecostal churches have changed over the years, but the use of the so-called “congregational songs” (also known as “praise songs”) have remained an integral component of the service. Although hymns are also sung today, congregational or church songs have never been discarded. The origins of many congregational songs are, as with many spirituals, unknown. They cannot be attributed to a single composer. Scholar Queen Booker said that Pentecostals believe congregational songs are God-given–a natural outgrowth of “glossolalic singing” or “singing in the spirit.”

However, other traditions were also present. In their heavy reliance on call-and-response, improvisation, foot-stomping, and hand-clapping, the songs signal a grassroots origin. “Pentecostal singing,” Booker argues, “freed the black worshippers to draw on the African traditions that the plantation ‘invisible church’ had kept alive. The songs have become canonized over the years, with each church developing its own repertory, although one might say, as a church musician once told me, if “you know one, you know them all.” The songs are so similar, in fact, that any Pentecostal church congregation can easily learn an unfamiliar one within a couple choruses.

Like “Nobody’s Fault But Mine,” many of these songs comprise one-line refrains, with the song leader improvising both melodically and textually. The leader’s improvising sometimes overlaps the response of the congregation, thus creating a dense texture. Intensity is achieved by the repetitive nature of the songs, the level of emotional fervor achieved within them, and the level of group participation in the music making: “A song might last as long as an hour or more, for different song leaders or soloists would ‘pick up’ where the previous one had “left off,” and the singing would continue.” Clearly, the character of these songs and their standardized performance practices allows the entire congregation to participate fully and enthusiastically. The repetitive musical style and the simply presented principles within the texts of these songs belie an underlying complexity. The songs contain elaborate rules of musical performance practice as well as a philosophy that is a unique blend of Christian theology and an African-American worldview. All of these together serve to teach group values on many levels and to engender communal solidarity or in anthropologist Victor Turner’s term, communitas, an important concept in the study of black vernacular music.

In her essay “Spirituals and Neo-Spirituals,” writer Zora Neale Hurston differentiates the aesthetic conventions of authentic spirituals and pieces of music “basedon the spirituals.” Included in the latter group, according to Hurston, were the art song spiritual settings of composers like Harry T. Burleigh, J. Rosamond

Johnson, Nathaniel Dett, and Hall Johnson. Their work, Hurston argues, exhibit a set craftsmanship and beauty while the others embody “unceasing variations around a theme,” new creations every time. While Hurston does not explicitly state that qualities of authentic spirituals embodied an African sensibility, the Pan-African theme unifying Nancy Cunard’s, Negro: An Anthology (1934), the book where her essay first appeared, supports this assertion. The African American art song tradition identified by Hurston came to the fore as a tide of cultural nationalism swelled and washed through black American arts and letters during the Harlem Renaissance reflecting what was known as the “New Negro” sensibility of the 1920s and 1930s.

I sense all of these historical and social energies in Simone’s performance. If you’ve ever heard one of the old church mothers get up and raise a song during testimony service, you know what I mean. They are usually not virtuosos in the typical sense of this word. Yes, the voice might not overpower these days; a mic is needed. No unearthly melismas, unusually large ranges, or vocal acrobatics to wow the crowd—just flatfooted singing with boatloads of nuance. And such nuance. In the first verse Nina restrains—a couple of turns on the first and third scale degrees, ending the last phrase on a very funk-ti-fied, Ray-Charles-esque minor third. Throughout the song she leaves off the “t” on fault, softening and “vernacular-izing” its presentation. In general Simone’s voice intrigues. It seems unsupported, being produced between throat and nose, which disallows the open, hollow sound “head voice” that many prefer to hear, thrown instead, forward through the nasal cavity. The vibrato is unsettlingly wide at the end of phrases suggesting a vulnerability, a little come-what-may, why bother. Some awwright, yeahyeahs, and heynows tossed in and you get the idea: this thing is about more than the notes, more than the lyrics, more than aesthetic sanctification. It’s about unrushed soul-sister-ism without the “please adore and objectify me.”

But, what about art song? Nina’s accompaniment, an understated support for her vocals, recalls some of the spiritual settings from the Harlem Renaissance forward. Although she’s loading this puppy down with blues licks, the moving inner voicings, and delicately marinated voicings on the i-V-I7-IV-VI-I chord lexicon of the song, seem so artful and crafty. As a classically trained pianist, how many of those art-song spirituals do you think she’d heard? When she ends with the descending passage and evenly articulated pianism beneath her belted and repeated “If I die and my soul be lost,” we are left to question any hint of vulnerability we’ve sense before. This is Nina: at the crossroads of charisma and restraint, artifice and earthiness. Clearly, it’s nobody’s song but hers.

Tags: Nina Simone, Nobody's Fault But Mine, Zora Neale Hurston

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It