From MusiQology contributor Martin Connor comes this in-depth look at the lyrics of Kanye West, erstwhile progressive-rapper-turned-Trump-supporter trapped in the Sunken Place. Connor takes a still relatively open, cognitively dissonant question—“Why does Kanye West support Donald Trump?”—and tries to make sense of it by reading West’s lyrics. He finds that this may not be as unexpected and disconnected from West’s career as one might think at first glance, and that the key themes of alienation and agency animate an existence consequentially made less miserable by Trumpian ideology.

Why has Kanye West aligned himself with Donald Trump?

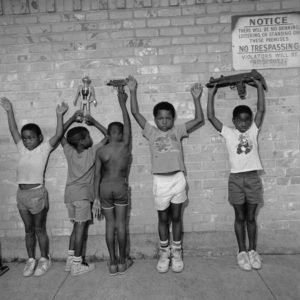

For all his bluster and self-aggrandizement, in his previous life, the Chicago rapper’s politics self-evidently skewed towards a more progressive position. “Never Let Me Down” from 2004’s The College Dropout discussed whites-only seating counters and voter discrimination in Chicago; “Jesus Walks” from the same record referenced police brutality a decade before it ignited a national firestorm in Ferguson, Missouri.

Both of West’s most famous media moments—the Hurricane Katrina telethon and the 2009 MTV Video Music Awards—were evidence of an activist streak around issues of media representation and racial inequity. The former—in which he frustratedly declared “George Bush doesn’t care about black people”—was a way to criticize the government and media’s handling of aid to poor black New Orleans citizens, spawning analyses of the media’s use of “looting” versus “finding” depending on the race of the person in the coverage. The latter is a tougher sell, but even the infamous “I’mma let you finish” MTV VMA interruption in 2009, we’d argue, is an attempt at addressing a wrong. In that case, West’s actions in defense of Beyoncé Knowles’s “Single Ladies (Put a Ring On It)” video were marked by a clear frustration: namely that raced ideas about excellence and femininity were to blame for why Taylor Swift instead hoisted the Best Female Video trophy.

But a lot has happened in the interim, and West’s metamorphosis emblematizes many of the strange and shifting forces in our political and cultural landscape. When he took the stage in San Jose, California in November 2016, nine days after Trump’s shocking electoral victory with the wounds of a nation still fresh and unscabbed, the rapper shocked the crowd. “If I would have voted, I would have voted for Trump,” he said. “That don’t mean that I don’t think that black lives matter. That don’t mean I don’t believe in women’s rights. I wanted to say that before the election, but they told me, ‘whatever you do, don’t say that out loud.’ Not only did I not vote, but there were a lot of things I actually liked about Trump’s campaign. His approach was fucking genius—because it worked.” Days later, West was posing in the lobby of Trump Tower wearing a Make America Great Again hat.

West was not done, returning to Twitter in April of this year to compliment conservative commentator Candice Owens and attributing his connection to Trump to be about the free exchange of ideas. “You don’t have to agree with trump but the mob can’t make me not love him,” another tweet read. “We are both dragon energy. He is my brother. I love everyone. I dont agree with everything anyone does. That’s what makes us individuals. And we have the right to independent thought.” By the summer, he was wandering the TMZ offices declaring chattel slavery a “choice,” a decision that alienated many of his most patient supporters. Earlier this month, he made a bombastic visit to the Oval Office itself, describing his MAGA hat as a “Superman cape.”

The media has had a field day covering these moments but seldom stopped to ask a fundamental question: What happened? How had this son of a Black Panther and a college English professor lost his sense of long-historical oppression, structural racism, and progressive activism? How and why could he take up with Trump?

Putting West’s documented mental health issues rightfully aside, we search instead for evidence that explains West’s worldview and politics. Instead of his on-again, off-again Twitter feed or awards show platforms, his most salient recent contributions to these types of discussions have actually come through his lyrics. “We shine because they hate us, floss cause they degrade us / We trying to buy back our 40 acres / And for that paper, look how low we a stoop / Even if you in a Benz, you still a nigga in a coupe,” he rapped in “All Falls Down,” his caution against the ills of consumerism in 2004. “No one man should have all that power,” he chanted in a postmodern reflection on his own impact on the culture in 2010. West’s lyrics throughout his career gestured towards progressive platforms and an understanding of systemic racism.

It seems, though, that a growing distance from that platform has been creeping upwards over time. Many of the lyrics of 2013’s “New Slaves,” thought to be more ironic at the time, read with a different discomfort now. “Feedback” from 2016’s The Life of Pablo contained the lyric “I can’t let these people play me/Name one genius that ain’t crazy,” a gesture towards a growing paranoia about a loss of agency that seems to key West’s turn towards the naked neoliberalism of Trumpism to come.

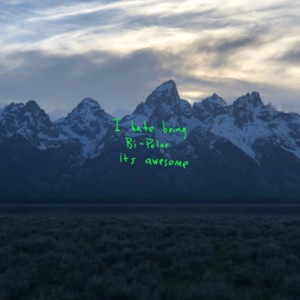

And specifically in the four collaborative albums he released in a flurry of activity between May 2018 and June 2018, West’s lyrics go from hints to clear signals, “speaking” to President Donald Trump both directly and indirectly. Together, it paints a picture of a strange relationship to himself, fame, and the presidency.

ye, “No Mistakes”

“Let me make this clear, so all y’all see

I don’t take advice from people less successful than me”

While of course the rumors about West, his wife Kim Kardashian and other famous folks being part of the Illuminati are ridiculous (or are they?), they definitely occupy a different world from the rest of us, from their paparazzi followings to the media coverage of their every move, word, and clothing item. As such, West’s alienation from his fans and the broader public left him looking for peers. In Trump, he sees a similar figure—a famous, free-Tweeter whose ability to speak new (dark twisted) realities into action was the hallmark of his success, whether that meant telegraphing fashion lines or collaborations or winning the Presidency. In a perverse idea of meritocracy, it asks, “Why trust anyone who hasn’t ascended to my level?”

“I’m my own strategist,” Trump once asserted, refuting the idea that he needed any help from others below him. Sadly, this combination of isolation and self-assurance similarly manifests in West’s life as well.

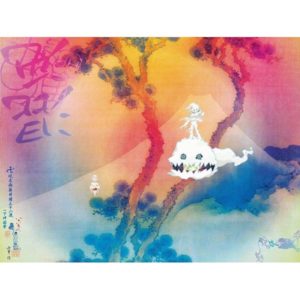

Kids See Ghosts, “Cudi Montage”

“Both sides lose somebody

Somebody dies, somebody goes to jail”

For all the wrong reasons, “both sides” has taken its place in the Presidential record after Trump elevated faultfinding above reconciliation after the white supremacist-catalyzed violence in Charlottesville, VA in August 2017. “You also had some very fine people on both sides,” was a dog whistle, a frighteningly false equivalency that equally implicated hundreds of peaceful protesters and violent white supremacists.

Who are the both sides of West’s lyric?

To be sure, this line could even be seen as a formulation of a rap trope that dates back to 2Pac in the early 1990s: “Only two places you end up, either dead or in jail.” But the ghastly resonance of this couplet’s opening phrase, echoing white supremacist messaging, makes it even more sinister: These lyrics represent a performative non-answer to the paradox that underlies Kanye’s fundamental conundrum: He feels both sides in an either-or world. And instead of accepting a foretold script—that he side with the “side” opposing Trump and white supremacy—he is resistant to what he perceives as a foreclosing of his own possibility.

ye, “I Thought About Killing You”

“Sorry, but I chose not to be no slave

Young nigga shit, nigga, we don’t age”

Strangely persistent in the history of American slavery is the reprehensible and ridiculous assertion that some slaves enjoyed their bondage and chose to remain in the employ of their former masters, even after emancipation. In reality, slave labor, then rendered as feudalist sharecropping and now performed in prison, has seldom if ever been about choice. This Uncle Tom status is abhorrent to a supposed “free thinker” like West, again, because of his feelings about agency. The idea that he could inhabit a world in which he has no choice is flummoxing. Trump’s presidency has flaunted norms and laws because, emboldened by his party’s subservience, has become powerful enough that he can do what he chooses at all times.

Also endemic to both men’s profile is their refusal to take firm ownership of any ideological stance they might strike on any given day. As Jon Caramanica wrote for The New York Times, “To Kanye’s mind, what happened on TMZ was a failure of language, not ideas. ‘I said the idea of sitting in something for 400 years sounds — sounds — like a choice to me, I never said it’s a choice…” The careful parsing of syntax, the recourse to the fourth or fifth definition of a simple word, is a favorite feint of Trump’s. In both cases, the men “choose” not to be held accountable even to their own words.

4.) NASIR, “Cops Shot The Kid”

“Stay tuned up and down your timeline

This fake news, people is all lyin’”

West’s relationship to the paparazzi and 24-hour-news-cycle—the “fame monster” his contemporary Lady Gaga notably named—is unlike that of the average person. The press salaciously covered details of his mother’s tragic death; stalk his family throughout the world; and make up a variety of stories about him and his inner circle. Simply put, it is easier to buy the argument of “fake news” when you, yourself, have watched an apparatus read deeply into your

Again, this speaks to a kind of alienation, where “fake news”—Trump’s nonsensical catchall for any reportage he doesn’t like—is an actual, real thing in West’s life. The loneliness of an existence perpetually in the public eye is key to understanding West’s naked individualism: No person, perhaps, has ever been more alone in a room that’s full.

Daytona, “What Would Meek Do”

“If you ain’t drivin’ while Black, do they stop you?

Will MAGA hats let me slide like a drive-thru?”

Perhaps the most pernicious dynamic throughout the panoply of the current assaults on objective reporting is the ready rejoinder that it can never hurt to simply “ask” a question. This assumes that the provocateur—the gadfly—asks all of their questions in good faith, even if that supposed agitator occupies a highly public position whose office necessarily carries the mark of both veracity and authority. By means of a sleight of hand that cloaks ambition in a coat of integrity, a presidential nominee can ask a foreign adversary to investigate his American political opponent, and then say that he was simply “joking.”

Clearly, an artist never can—nor should—be held to the same standard of truthfulness as a sitting American president. To do so would be to outlaw the rich traditions of satire, parody, and irony. So Kanye may feel free to play the role of mischievous free thinker all day. But whether he desires it or not, thoughts lead to actions, and actions have definite, real-world consequences. In this case, he takes a documented phenomenon and questions its reality, pairing that with the idea that his hat might be the thing that makes him feel closer to others who breathe less rarefied air.

“Why did Kanye West become a Trump supporter?” is a difficult and strange question to ask—much less answer—because one of our nation’s most influential voices has aligned himself with the white supremacy he once roundly and poignantly critiqued. These similarities of grievance, resentment, egotism, and falsity may not be their only shared personality traits, but it is clearly more than enough to cement their bond, both now and in the future.

Martin Connor is a music teacher and writer from Philadelphia, PA, with a music degree of high distinction from Duke University who is currently studying for a master’s degree at Brandeis University. His research focuses on the vocal melodies of the rap genre. He is the founder of RapAnalysis.com and has contributed freelance articles to HipHopDX and Complex. He has also had his work appear in Cambridge University’s Popular Music journal and the anthology Eminem & Rap, Poetry, Race. He has been featured on Harvard University’s The Hypertext research project, directed by Harry Allen, teaches rap lessons online through the music school LessonFace, and has authored a book, The Artistry Of Rap Music, (McFarland), scheduled for release in late 2017. He welcomes all comments, compliments, insults, and restaurant suggestions at mepc36@gmail.com.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It