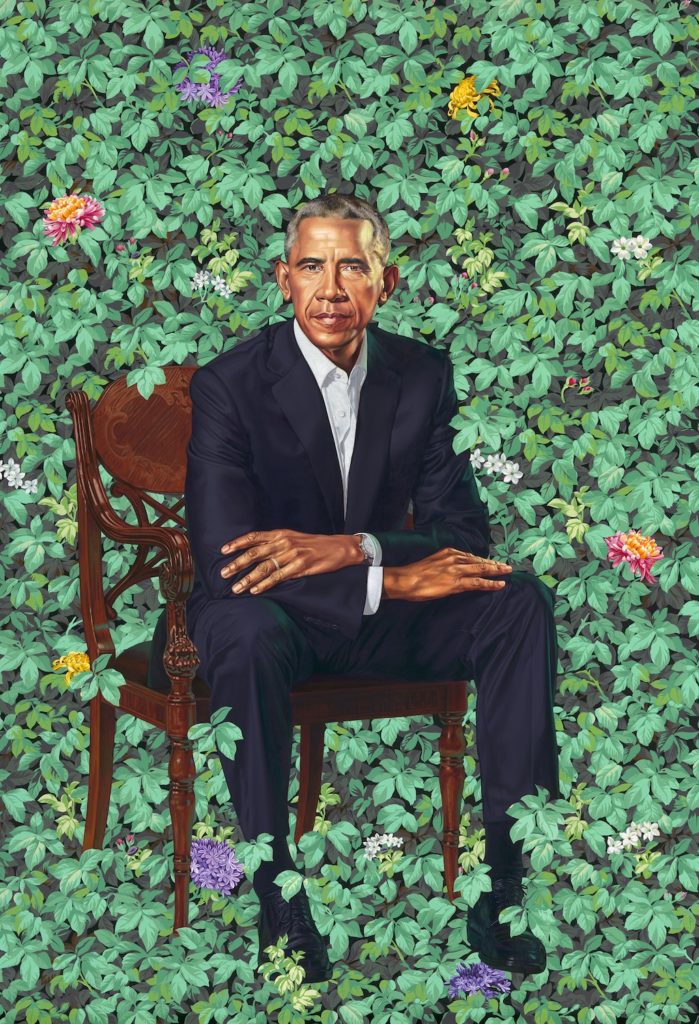

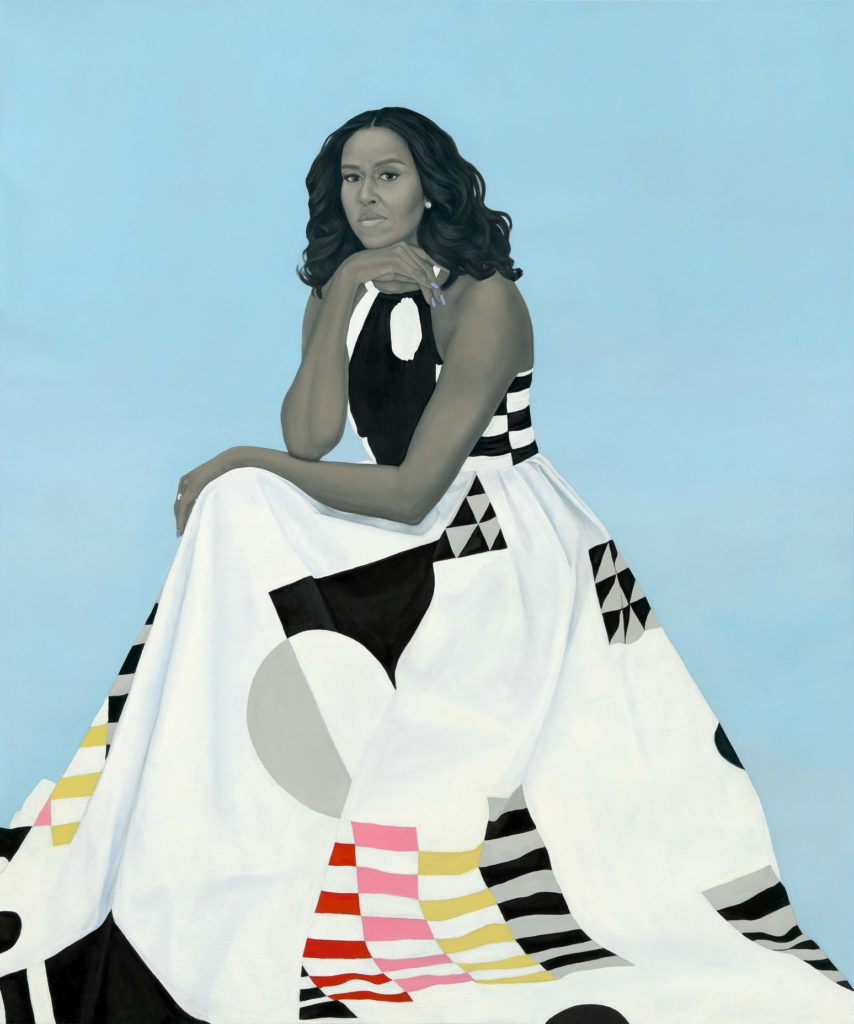

With the unveiling of the Smithsonian-commissioned portraits of former President Barack and former First Lady Michelle Obama came a sense of wonder, attention, and excitement never before seen in the usually staid and stodgy world of White House art. Eschewing tradition, the Obamas selected Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald, respectively. Both are African American artists who focus on representation, race, and identity in their work, and both of the portraits—the former President seated at-the-ready in a garden of ivy and the First Lady adorned in a tremendous and evocative quilt-like gown—are vivid, powerful reflections on the medium, the nation, and the people they portray.

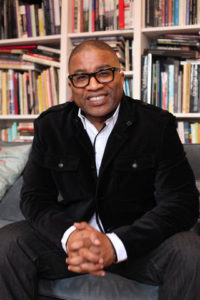

We sourced responses from MusiQology’s own First Partnership, asking Dr. Guy Ramsey and Dr. Kellie Jones their initial impressions of the portraits, their cultural impact, and future significance. Both gave us new ways to think about the moment and even more reasons to realize its importance.

Dr. Kellie Jones on the Art World’s Productive Crossover

Most of these types of portraits are done by portrait painters—they’re of a certain genre and they’re not really a part of what I would call the art world. As a result, they don’t necessarily figure in art history generally; instead, they figure in presidential history. You look them up later. Maybe earlier in the history of the form, they were well-known painters of their time, but that’s clearly not the case now.

So what’s different and important now is that Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald are well-known artists…well-known African American artists. Now you can teach about their portraits in addition to the rest of their work in the art world. It’s a certain kind of milestone even though it’s not technically the first African American Presidential portrait (that was by Simmie Knox of the Clintons in 2004). But it’s a milestone because of who these artists are and because of their style.

Both of their styles are very distinctive. Obama, floating in ivy on a chair…it’s so different. This is very representational but also abstract. Wiley and Obama both have African fathers. They’re both West Coasters. They were both raised largely by single mothers. As the first black woman Presidential portraitist, it’s even more special for Amy Sherald. Her work even goes towards a more archetypal abstract thing that is, even if subtly so, different.

This is fantastic. I wish I was there at the ceremony. The paintings are…I can’t wait to see them. They’re beautiful works and what’s impressive about them compared to the usual portrait is that they’re actually something you want to go look at. You can do similar analyses of other portraits, but it’s different. These works are so vibrant. Salamishah Tillet has an image on her Instagram that has a grid of the recent portraits; just look how different and striking it is.

These could eventually hang in the White House. Think about that. It’s a different way of even conceiving what a portrait is, and the fact that the first black President and the first black First Lady chose these artists, is significant. There’s so much in these works that we can talk about. There’s actually much more to talk about than normal. It actually becomes a new way for us to talk about American history.

It is also about the continuing legacy of the Obamas. They keep making strides in terms of culture, what it might say for the library they’re building, and the role of art and artists in history. So these portraits bring a lot of things up. I don’t know if they answer them, but they signal a different kind of engagement with African American artists and diverse types of artists in the future.

Dr. Guthrie Ramsey on Aesthetics and Discourse

One thing that I have been witnessing on social media is very strong opinions about the portraits. I don’t have a strong opinion about what was done (I like them both in their own ways), but what makes me happy is hearing public, heartfelt arguments about aesthetics and representation. That is so important. It makes me believe that I haven’t been lying in my books and to my classes. People think that historians exaggerate and we go back and think about these past arguments about aesthetics. They think we’re over-stating them in the service of a case we’re trying to make.

But when you live through a moment like this, even when the argument will last two days until somebody drops an album or a commercial comes out that people don’t like or Black Panther or a cartoon or God help us someone get shot, in this moment, it’s about the cultural politics of representation in an aesthetic medium with histories and subjects that have histories. It’s all colliding, people want to talk about how it should and shouldn’t go, and I love it. It’s about what I teach all the time, whether it’s the 1940s, the 1900s, or the 19th Century. These things matter in the public discourse and we aren’t always thinking about how they matter until something like this happens.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It