Honestly, I’m weary of conversations. The disappointment comes less from the exhausted topics

(gender, race, etc.) and more from my community’s lack of nuance on such themes. Folk

involved are crafty with talking at, over, about, and/ or through people, but haven’t

acknowledged the need for listening skills, and most importantly, compassion and critical

thought. It would be great to see the lessening of basic conversations and the increase of

compassionate and critical dialogue in chances that we could assist in the process of healing that

is needed by so many Black folk today.

These limited addresses gripped me the hardest in late 2016 when I considered committing

suicide. Painfully inspired to jump from New York City’s High Line, I was under the impression

that few in my community would have believed how emotionally and spiritually crushed I was.

I’d suffered the biggest heartbreak of my adult life, almost lost my mother (for the second or

third time), and was on the brink of failing out of university. In short, I had no one to really turn

to and most around me had not yet shared a wider concern that Black men need love and

compassion… not blame and dismissal.

While searching for the best therapist that my lack of money could buy, I turned to a few people

who were constantly there to support me… the elders and ancestors in my record collection. I’m

fortunate enough to have grown up around some great folk who showed love, kept their word,

and didn’t take no mess. What I remember most is the beauty and intensity of those face-to- face

interactions; something missing in today’s digital conversations around important topics. It’s

easy to hide behind keyboards and type out loud words, while not aware of someone else’s silent

suffering.

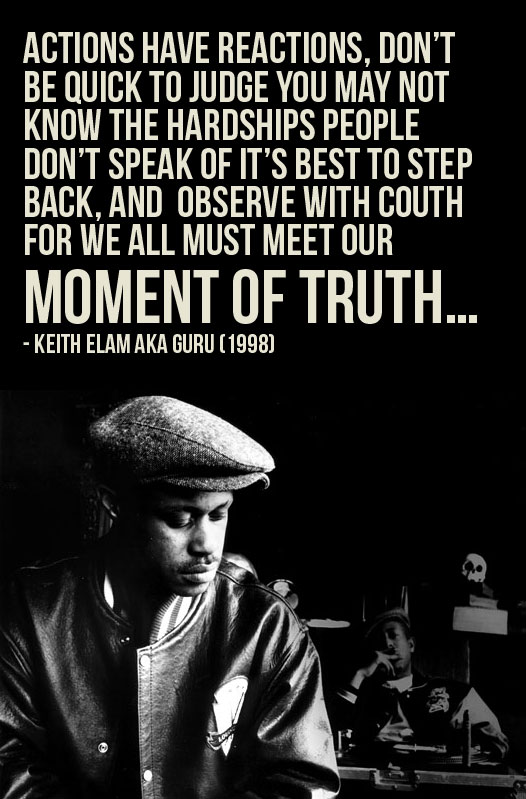

Throughout my years of undiagnosed depression, anxiety, trauma, and pain, the spirits on my

records have been a constant source of healing, reflection, and knowledge for me. Not simply

black circles containing music, history, and lineage, these Black slabs also become safe spaces

when my surroundings offered me no solace, compassion, or understanding. Never did the music

of my choosing refer to me as an animal or shame me as if my shortcomings were genetic (i.e.

“all Black men are dogs” or “you’re just like your father”). The attention the musicians paid to

their performances was meant to welcome me into their emotional states and thought processes,

as opposed to the constant rejection I faced by peers and romantic interests in my community as I

grew older. Never shielding me from harsh realities, my collection of Black musical geniuses

gave me lessons of life and messages of encouragement. Education had never been so true and

pure.

There were also secrets within those grooves. Not just breaks and open sections that would lay

the foundation for Hip-Hop, House, Techno, Broken Beat, Grime, etc. but actual examples on

how to communicate with my people. On many of these records musicians displayed interests,

respect, and unity. There were dialogues happening. Whether rehearsed or improvised,

musicians had to look each other in the eye to catch signals on where the music was heading

since the musical version of autocorrect hadn’t been invented yet and backpedaling wasn’t an

option either (unlike the synthetic digital “mumbles” of today, mainly created within isolated

boxes and primarily listened to on tinnitus gifting headphones or deafening auto systems. These

experiences, I believe, have limited the opportunities for listeners to enjoy sounds of any sort

within a healthy, natural environment, thus also compromising their ability to fully engage and

communicate when needed). Sure, there might be sheet music in front of these learned musicians

as a reminder of chord changes, but Black folk don’t work within the structure of planned

existence, we work around it. Living breathing organisms that literally walk, talk, and dance to

the improvisations of life came before me to bless with better understands of who I was, where I

came from, and what I could achieve.

Dialogues and partnerships between brothers and sisters like Melba Liston and Randy Weston,

John Lewis and Milt Jackson, Nina Simone and Weldon Irvine, Dorothy Ashby and Frank Wess,

Eric Dolphy and anyone he played with taught me more about communication than any of my

childhood language teachers. A listener can hear the long lasting friendship and camaraderie

between Charles Mingus and Dannie Richmond, understanding how in sync two had to be to

become one. The same can be said for Percy Heath and Connie Kay, whom not only represent

the finest of Black Classicalism in rhythm, but were also two of the music’s best communicators.

When couples like Alice and John Coltrane, Trudy Pitts and Mr. “C”, or Shirley Scott and

Stanley Turrentine hit the studio their presence was not only that of Black folk who read each

other’s musical minds, but they also displayed Black love, Black partnerships, and Black

creativity in matrimonial pairings.

Not all in-the- moment transformative spaces (like bandstands) feature more than one person

though, as there should be space here to acknowledge and appreciate solitude. During the many

difficult years of my life, I spent much time locked in my room (a practice I’m still accustomed

to). The solo piano sides of Thelonious Monk, Ray Bryant, and Mal Waldron eased my

melancholy, while the gentle voices and quiet guitars of Elizabeth Cotton and Mississippi John

Hurt gave me opportunities to turn my sadness into courage. For me, these spirits lent themselves

to better discover and hear the world; with properly attuned ears and a heart ready to try again.

I was learning how to be resilient, while being taught forgiveness toward those who brought me so

much pain.

But now? Now I’m not so sure about the state of my community. I grew up with the voices,

examples, and messages of the elders in my ears, however the majority of what I see is what my

Grandma Mary would call frightenin’ fussin’ and fightin’ (taking part in such behavior herself

every now and then, she still managed to be a great well of forgiveness for her grandchildren

growing up in the turbulent 1970s-80s). The public display imbalance in conversation has had

harmful effects on the sensitive, traumatized, and impressionable man that I’ve become. Having

lost many loved ones to the streets, poor health, and suicide, there are still times when I wish to

escape all that I know. Drinking consumed me, and as I reached out for help from loved ones, I

was either met with dismissal concerning my pain, or another round of poison to continue the

process of temporary numbing.

Music and dialogue are sections of the same discourse that need to be had by Black folk young

and old, man and woman, as I feel they can still be a part of our healing process and

communicative growth. When I walk the streets young Black women rarely look my way, and it

hurts to the core, just as much as knowing that women I hold dearly face constant harassment in

public places from brothers… typically without any protection. Our keyboards filter into our

public diaries, while simultaneously work as daggers piercing tender spots of those who long for

peaceful interactions. Black men have slowly started finding each other via these same outlets,

and even though our words are often silenced, connections are happening around mistreatment,

resentment, and rejection from those we wish to be closest to. Many of us have been/ are putting

the best foot forward to be present for/ in our communities.

A quick glance at the rock bottom has taught me a lot of things. I try to be present in the moment

a bit more. Offering my assistance to those in need is something I’m trying to get better at. And

making sure my few friends know that I love them is a must. However, I’ve also realized that I

need to be more honest with those I care about, and sadly a lot of folk would rather stick to

narratives degrading Black men as opposed to learning how many of us truly feel in regards to

our positions in the community. I speak up for myself more, and brothers aren’t always going to

be praised for that. All I can do is try to treat the rest of my life like I’m on the bandstand… like

I’m Jimmy Garrison looking at Elvin Jones ready to start another transformative portion of our

dialogue.

(Authors Note: I didn’t jump, but that doesn’t mean I don’t continue to fight feelings that make

me want to.)

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It