Trading Fours is a new recurring column at MusiQology where we present the often-obtuse format of academic conversation in a more organized and easily consumable way. We set two voices in conversation around a theme or set of topics, restricting each contribution to four sentences maximum. This keeps conversation concise and creates a more dynamic interplay to help ideas and through-lines flourish in a format that is more readable than most academic work. We believe it cuts to the core of MusiQology’s mission of accessible criticism with appropriate consideration and nuance.

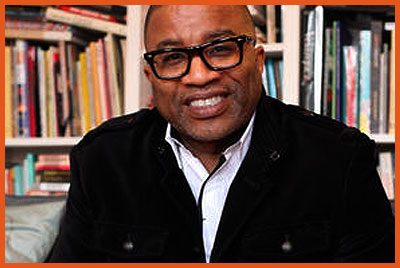

For the first edition of Trading Fours, MusiQology’s Editor-in-Chief Dr. Guy Ramsey and Managing Editor John Vilanova discuss “Race, Art, and Essentialism,” a piece recently published in The New Yorker by George Packer. In what begins as a critique of novelist Rick Moody’s review of James McBride’s new book about James Brown, Packer takes up the decades-old question of race and criticism: What does the race of a writer (or a performer) say about his or her ability to address a piece of music? The essay moves through examples contemporary and historical from Amiri Baraka’s “Jazz and the White Critic” to the story of rising black opera singer Ryan Speedo Green.

This debate usually asks us to draw a line in the sand: Do we believe that black writers are somehow more equipped to write about raced-black musical forms than others? Or is that suggestion multiply racist in that it essentializes black writers and precludes white writers’ contributions? The inaugural Trading Fours suggests rightly that the truth is neither of these poles.

Guthrie Ramsey: This one really struck a chord with me because I’ve been teaching and writing about this idea of the relationship between race and identity and identity and musical taste or musical insights for a long time. And it was a little discouraging because some of the progress I thought those of us who work in these areas had made. Some of these arguments are 75 years old and they’re still having them. And they’re still having them on the same terms?

John Vilanova: Why do you think this issue continues to be framed this way? And what’s a specific example of something that’s still getting you about this?

GR: When writers say that Stanley Crouch has more insight into jazz because he’s black, I don’t like other writers who won’t give that a generous reading or try to see what that question is trying to accomplish. I find them reductive because you always have to reduce people in order to make some of these arguments. You have to say that Moody’s piece was totally ridiculous or that Amiri Baraka was. There’s no room to consider the merit of either argument as such.

JV: I read Blues People for the first time a decade ago as a young white undergraduate and I was like, “I hate this book” because it felt like I was being pressed out of something. In hindsight, I realize that was such a privileged idea to suggest that I had a right to be angry about about Baraka’s claims in that book. But what that central claim is really about is difference and how difference manifests itself differently, right? Baraka and Crouch weren’t able to say more or less; they were able to say things from a specific perspective.

GR: And differently—they could say it differently. I find that writers were not as honest as you were when you encountered that text. There’s a lot of criticism that I read out there where that’s really the sentiment but it’s never really being put on the table. Eliding that blurs the specifics of what we’re really talking about.

JV: And it’s not because they’re appropriately measuring their criticism, right? It’s because they can’t figure out how to middle-ground it. They can’t figure out how to say, “It’s unique, important, and interesting,” and they can’t say, “I’m left out of this entirely.” So they don’t say anything at all, and their work lands in this place where the subtext of what they’re suggesting does all the work.

GR: And that’s very frustrating because I feel that when Baraka was writing that, he actually felt it and he was honest enough to just put it out there. So I just think that we need more honesty in what we’re really talking about before we can move on about some of this stuff. Instead, ask, “How can you really, really take someone seriously when they say that you can’t write about something?” And since when has that worked?

JV: Exactly. What happens is that instead of trying to think through the argument, critics sit down to write about the fact that somebody said, “We couldn’t write about it!” Critique often rings hollow without offering solutions, and it becomes very difficult to do that in ways that don’t just recenter something else. We want to critique the center—how do we do that?

GR: Right. What I think we avoid is the reality that everybody’s going to have a perspective. Each perspective should be valued on its own merit; it should be valued historically; it should be valued situationally. It should be valued as rhetoric.

JV: And what happens is that some people (on all sides of the political spectrum) overlook their own perspective. People may claim to be progressive, but then what happens when their actions are still reinstantiating the things they claim to be opposing?

GR: There are some people you would never think are misogynists who are by virtue of this. I don’t know how, for instance, anybody could overlook the fact that they’re affected by things like race, misogyny, and sexism. That’s a very, very powerful discourse that controls a lot of thoughts, a lot of actions, both conscious and unconscious.

JV: People want to be able to make purchase on something. If they feel they are “woke”—if they draw a dichotomy between “woke” and “not woke” and determine which side they’ve landed on—then they know more than everybody else already does.

GR: It’s amazing to me how much history people are willing to ignore to make their points. That’s one of my main criticisms of this Packer piece. I just thought, “Well…Why would a black man in the early 1960s want to claim that he was in a unique position to talk about this stuff?” I don’t know why that’s a hard thing to understand if you know history.

JV: And how that history conditions your position, right?

GR: One of the things I’ve been thinking about recently is that so much of hip-hop scholarship and journalism is so self-reflexive and autobiographical, even more so than what jazz criticism was in the 1930s and 40s. It was criticized for being too much about the critics themselves.

JV: How was that something you reconciled when you were writing Race Music?

GR: I said from the outset, “This is autobiographical.” There’s a difference between being self-consciously autobiographical and un-realizingly inserting yourself. It was like, “This is what the autobiographical might do to criticism.” It didn’t just pass itself off as something other than what it was.

JV: So that was something that you were consciously thinking about?

GR: Definitely. Because all writing and all scholarship is as autobiographical as Race Music is. That was one of the points I was trying to make. So the question is: What are you going to do with that insight, that baggage, or whatever you’re going to call it? What are you going to do with it?

JV: Well what happens is if you forget about the author (yourself or someone else), you forget about subject position and you wind up appealing more to empiricism or truth with a capital T. Why does science not emphasize the author? Because they’re talking about facts.

GR: I’m very interested when people try to make these claims. It always perks my ears up when people write as if objectivity is possible and they’re going to argue about that.

JV: Even if it isn’t objectivity of author, people believe in different objectivities of evidence. So with our “viral” Kendrick Lamar piece, quantitative social scientists got excited about it because they thought they could quantify it. They wanted to run statistical models on it to see if it’s actually something statistically significant. And if it is, then it’s “scientific.”

GR: I’ll tell you what: If they can come up with that kind of evidence, more power to them. Some people do require that, for better or worse.

JV: But if it’s not statistically significant, then I want to say, “This is a social fact—racism—even when the empirical fact suggests that it’s not. This is something we believe to be true and experience to be true.

GR: I don’t see a contradiction between having experienced something and knowing how to do it and saying that you don’t believe in it after it’s done. It makes the story more interesting to be able to speak across different contexts.

JV: But for many people, that becomes the real argument. If that is taken as the strongest evidence there is, it continues to keep a historically specific version of the empirical as the most important thing. And we’re proving ourselves to and within a system without being able to critique the means by which it measures. Circling back, is there anything more you want to say about the article?

GR: I think the proof of all this is how he was just far too dismissive about Baraka’s contributions. That is so easy to do when someone has passed on. And Baraka was writing in a very specific context that is under-acknowledged here.

JV: Influence is a very difficult thing to figure out. So if we’re talking about, “How do we quantify something?” someone like Baraka’s influence is almost inconceivable, right?

GR: Exactly. But to see it just glibly tossed aside for an argument kind of reifies what he claims to be arguing against—condescension and essentialism. I can’t think of anything more condescending than how he reduced Baraka’s work.

JV: There’s something dishonest in that style of writing. To affect cheekiness. To affect superiority. To affect criticism to somehow make it more legitimate.

GR: Since I don’t write like that, it’s hard for me to respond like that. What the reviewer was talking about wasn’t relevant to the book. So I don’t waste my time when it’s not contributing to what I’m trying to achieve.

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It