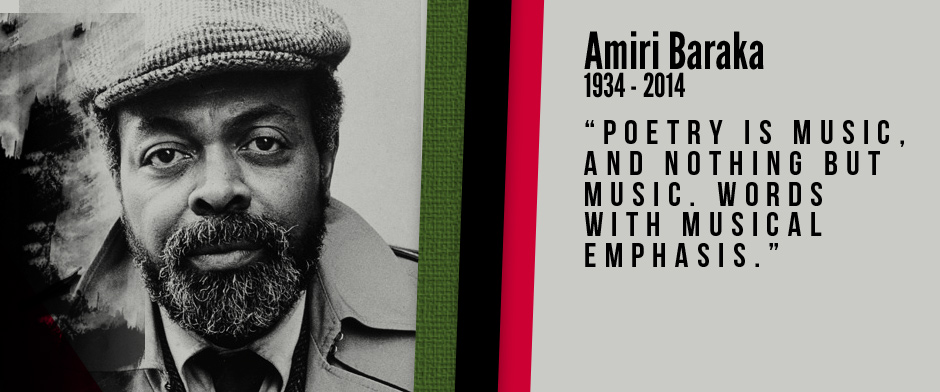

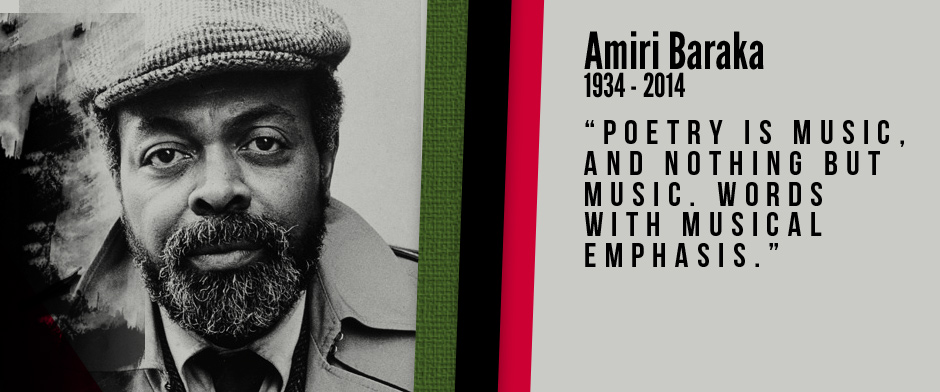

The January 9, 2014 passing of Amiri Baraka, the great poet, activist, lion of black letters and ideas, music historian, our great eulogizer, the bluesman, and jazz critic has left an incalculable void. I’ve taught his work in many classes, cited and discussed it in my own books and articles, admired its force, struggled with and was challenged by some of its premises. Surely they’ll be waves of retrospectives on his work in the coming years, and it will deserve all that attention and then some. But I still can’t believe that “B,” as I called him in conversation, got outta here like this. Just out. Like he stopped before the solo was finished. Dropped the mic in the middle of trading fours with the band and suddenly took his seat with the ancestors.

As I’ve read the outpouring of support, condolences, tributes and memorials on social media for Baraka, it’s clear that many others are also processing the impact of this man and his art out loud. I’ll be calculating the void he’s left on my own terms for a long time. Like many of us, I can’t believe he’s not here to offer the right comment, to articulate our consciousness, to give us that elder speak when we need it, to make a stick, stone, or shield out of some powerful words or a brilliant turn of phrase. The main-scream media is a whole other trip. It’s been disappointing to hunt down his obituaries in various media outlets only to find as much of the “bitter bullshit” he talked about in the poem above as the deserved roll call of his towering literary achievements and staggering activism.

My own thoughts elide the private and public—probably the residual effect of having a famous family member for the last decade or so. Before he was my father under the law, he was one of my literary beacons, a father outlaw—the dude who stood up, made his moves, said his piece, shot up the place and then counted up the costs after the reviews were in. I’m not prone to tripping around famous folk—I didn’t get that groupie gene, but I was in awe of him.

The first time I hung with B, his daughter Kellie and I were waiting for him in the lobby of the Brooklyn Museum to walk him through her new exhibition on the painter Jean Michel Basquiat. I really didn’t know what to expect. The previous time I was in the same room with him had been a few years prior during a conference around the documentary I’ll Make Me A World. His panel followed mine. B, of course, tore the joint up with some raw, uncut science about art and politics that nobody else had thought about or had the nerve to say. And when he exited the stage, he finished his diatribe under his breath, in my face, and before I could respond he was on his way. I froze. I think he said he disagreed with something I had said. It was hard to tell because, like I said, I was frozen.

When he came through the revolving doors of the museum, the brother strolled across the lobby cool-in-a-muthafukah–that unflappable uncle/older cousin smoothest, self-assured cool. The kind you wish you had. One of the things I dug about kicking it with him was that he would make me bust my side laughing at some one-liner that I understood to my core. The humor of the Signifyin’ Monkey tales that make you love being in the universe. The humor that makes 6-year-old boys and 66-year-old men find a groove and not lose patience in a crowded barbershop. He was the best at it.

After the tour and at lunch he narrated his side of the New Jersey poet laureate drama. Governor McGreevy asked him to apologize or resign the post after his poem “Somebody Blew Up America” caused a big “discussion.” He refused, and they legislated the position out of existence. When McGreevy fell out of political favor because of an extra martial affair and coming out of the closet, in his own words, as a gay American, B did what any self-respecting revolutionary would do. He sent McGreevy a telegram that said: “whatever you do, do not apologize and do not resign.” Don’t eff with a poet, okay?

And with that, my Baraka adventures began…

Tags: Amiri Baraka, blues people, leroi jones, rip

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It

![[Video] Greg Tate Delivers Timely Keynote Address at SEM](https://musiqology.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/gregtate-225x225.jpg)