I’ll admit it.

Saying goodbye to summer’s reprieve is always a shock to the system, but as a hopeless academic, the fall has always been a great time of year. It means a new academic startup, meeting new students, new materials to learn and teach, and, always, always a fresh outlook on familiar materials. It’s another opportunity to grow, test your mental limits, and throw yourself into another season of concerts, exhibitions, and public lectures.

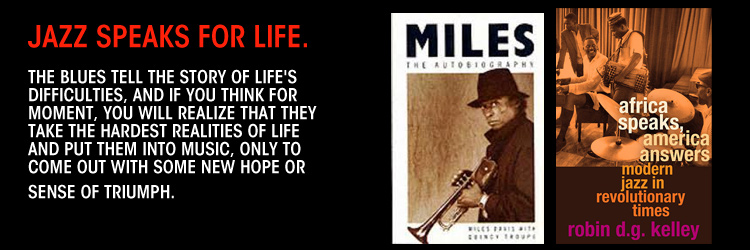

This semester I’m fortunate to teach a course titled “Jazz Speaks for Life,” a new twist on the history of jazz that takes into account the various meanings that people have invested in the music, the substantial role of women in the art form, and the global impact of the genre. The title was suggested by our graduate teaching fellow Josslyn Luckett and is taken from remarks given by Martin Luther King at the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, in which he said:

“God has wrought many things out of oppression. He has endowed his creatures with the capacity to create and from this capacity has flowed the sweet songs of sorrow and joy that have allowed man to cope with his environment and many different situations.”

Jazz speaks for life. The Blues tell the story of life’s difficulties, and if you think for moment, you will realize that they take the hardest realities of life and put them into music, only to come out with some new hope or sense of triumph.

This is triumphant music.”

We’ll read the following books in their entirety together with other supplemental writings as we journey through the music’s history through a sonic and theoretical framework designed to achieve the following:

to increase students’ knowledge of musical concepts and terminology as they relate to the study of jazz

to increase students’ knowledge of jazz repertory and some of the primary figures in jazz

to increase students’ skills in active listening

to increase students’ knowledge of the shifting historical contexts of various jazz styles

to increase students’ ability to write and talk about music

Selected Texts

Guthrie Ramsey, Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop

Guthrie Ramsey, The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History, and the Challenge of Bebop

Robin Kelley, Africa Speaks, America Answers: Modern Jazz in Revolutionary Times

Farah Griffin, If You Can’t Be Free, Be A Mystery: In Search of Billie Holiday

Miles Davis and Quincy Trope, Miles: The Autobiography

Burton Peretti, Jazz in American Culture

During the first couple of weeks the course takes on the question “how does music mean?,” which is a core issue I deal with in all of my classes. What we try to understand is how the conventions and sonic gestures in a piece of music signify meaning to listeners. Students are always intrigued by this notion: that music can be understood as a knowable and teachable language system that communicates clear ideas about world, and that this holds true for instrumental music. It’s not that students believe that music doesn’t mean anything. It’s that they are stunned and empowered to find out that they can learn to decipher music’s codes vis-à-vis the various social arrangements and historical moments in which music sounds.

It’s always difficult knowing how to begin the journey. I was rummaging around Facebook and found this poem by Lucille Clifton on the writer Kiese Laymon’s Timeline. We talked about it as if the protagonist was Jazz, herself, a miracle of sound, science, and society in the early years of twentieth century American and would become a major cultural force around the globe.

won’t you celebrate with me

won’t you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my one hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

~Lucille Clifton

Indeed, there were many arbiters of good taste who wrote about jazz in magazines during the 1920s not as something to be celebrated but as if it were a virus that needed to be contained. How far we’ve come as the music is celebrated today as an American institution worthy of honor among the pantheon of great arts that this country has contributed to the world.

Although the book isn’t about jazz specifically, Race Music: Black Cultures from Bebop to Hip-Hop’s first two chapters take up the issue of musical meaning from two radically different angles: the politics of the personal and the theoretical. Written as musical memoir of sorts, the first chapter of Race Music is meant pedagogically to get students to understand that it’s okay to have and celebrate one’s personal feelings and thoughts about their relationship to music. We always hear with our own ears. But what we try to understand is the social constitution of those personal reactions to music, which is taken up theoretically in chapter two. And thereby we can begin to engage the musical worlds of others—no matter the fact that we may be separated by culture, time or by other factors of identity.

Taken together, we are dealing with two large ideas: what do you hear and what and especially how does it mean? In my formulation, this “cultural studies” model of music criticism attempts to illuminate what the “cultural work” of music is for listeners and musicians. We want to know what various styles and genres mean and how they achieve their signifying affect. Here are the beginning steps in this process of analysis that we’ll learn throughout the semester. We first identify a performance’s significant musical gestures (an improvised solo, a walking bass line, a radical lyric, an unusual instrument combination). Then we position these gestures within a broader field of musical rhetoric and conventions by comparing them with other examples of styles at the same historical moment. And then we can theorize these with respect to broader systems of cultural knowledge: how are people (other musicians, audiences, and critics) reacting to the stylistic reproductions or disruptions represented in a musical work.

What is Jazz?

Of course, this is the first question on the minds of the new jazz listener? And there’s no “best” way to approach it accept to plunge in, headfirst. Definitions in most music appreciation textbooks such as Mark Gridley’s popular Jazz Styles: History and Analysis, say that jazz, first and foremost must have improvisation as a key feature. It embodies a rhythmic conception called “swing” that gives it a dance spirit and feeling. Jazz also refers to a specific repertory of songs called “standards,” both composed by jazz musicians themselves and taken from popular songs of the Tin Pan Alley tradition. But what we quickly learn from a historical perspective, what jazz is—on the formal or sonic level—is a very dynamic concept. Like any living thing what jazz comprises (and what it means) is being constantly revised. And the debates are rich, and dynamic and legendary.

Let’s begin with four examples of what jazz means: the Ken Burns’ Jazz documentary (2001); the 2010 documentary Icons Among Us, directed by Lars Larson and Michael Rivoira; the iconic 1959 short film by musician Edward Bland, The Cry of Jazz (with a score by Sun Ra); and the online campaign of Jazz at Lincoln Center. Each have their own take on the definition of jazz, and it is a fascinating study to see how each frames its positions.

Ken Burns pushes the nationalistic angle. Jazz is America’s music, a creation emblematic of everything America represents in its socio-political and mythic ideologies. Rugged individualism, democracy, heroism, collective striving and so on—it’s a symbol of how we have overcome struggles such as the Great Depression and segregation, and Miles Davis’ questionable fashion and musical style choices in the 1970s. Icons Among Us seeks to expand the traditional aesthetic boundaries of jazz by featuring a very self-consciously interracial cast of musicians who push out from previous stylistic conventions. Jazz at Lincoln Center’s, Feeling Good at Jazz, features brief, personal reflections by contemporary jazz stars. Their words are meant, in totality, to stress jazz’s “universal” qualities—it belongs to everyone. If you rummage around the site, you will, of course, encounter Wynton Marsalis’ casual and astute philosophies about the elemental qualities that make the music tick on the formal level.

As the most controversial example, The Cry of Jazz is philosophically and aesthetically a dizzying mash-up. It’s part Blues People, part Beat poet fantasy, part Twilight Zone, part Sweet Flypaper of Life, part Gordon Parks meditation, part Twelve Million Black Voices, part musicological analysis, part primitivism, part nationalism and part integrationist diatribe. With a musical score by Sun Ra, it’s an astonishing document of Mr. Bland’s social and cultural thesis that details what jazz was to him. Set in a integrated house party, the film revolves around a question and answer session that’s scripted and very didactic, covering the origins and meanings of jazz. The factual hits and misses aside, it’s certainly a film meant to inspire dialogue, particularly in a classroom setting where students are already acquainted with standard, narrative histories. It mixes statements about the jazz’s sonic language and the racial politics of the music from a black cultural nationalistic viewpoint.

The Jazz at Lincoln Center Youtube Channel

Ken Burns’ Jazz (Introduction)

Icons Among Us (Trailer)

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nLYogj8QpHA

The Cry of Jazz

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_RAMF9X3JFc

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vlm_9oMzAU4

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-30H4MH7Tv8

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ZiwBvHPjMo

After digesting these examples of varying opinions about what jazz is, we can next time take on three foundational aspects of the course: 1) developing some technical language to understand the music; 2) the fundamentals of “cultural studies”; and 3) some social context to understand the emergence of jazz in American culture. See you next time.

Tags: ethnomusicology, fall semester, Jazz, musicology, upenn, World music

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It