The words in the title are taken from Robert Hayden’s poem “Frederick Douglass,” which was written as the movement called “Black Consciousness” defined African American cultural nationalism in the mid-1960s. In it Douglass envisions “a world where none is lonely, none hunted, alien . . . ” This, of course, would be quite a dream in its time, one that was inconceivable to many. Strivings for this “beautiful and terrible” thing called freedom would eventually culminate into a cultural nationalism, one with roots in slavery but with an eye on the present and future, particularly after the Emancipation Proclamation.

Expressions of cultural nationalism served political functions as well as artistic modes of creation. Music (and visual art) figured prominently as expressions of “black nationalist” thinking but its force would be disciplined, harnessed, and directed in the community theaters of the literary. Indeed, a new black world was being made through literary constructions as early as the eighteenth century.

In Becoming African American: Race and Nation in the Early Black Atlantic, James Sidbury writes that literary acts of resistance by writers such as Phillis Wheatley and Ignatius Sancho represented “a language of African identity” as they wrote against empire and used “the master’s” tools to do so. They, and other black writers, used literature to create a discursive space for the making of the “new” African subject, paving the way for the heroic journey from “thing to human being,” in the Anglophone world. This construction of African identity occurred in letters but also in the way black people founded many institutions—schools and churches included—with the term “African” in their titles. For Sidbury, Wheatley and Sancho essentially wrote into existence a black kinship that was based on shared common interests and suffering rather than on mystical blood ties. These cultural nationalisms were forged from both structural racism and through acts of self-fashioning toward social uplift.

Visual culture became another realm in which representations of black cultural nationalism lived.

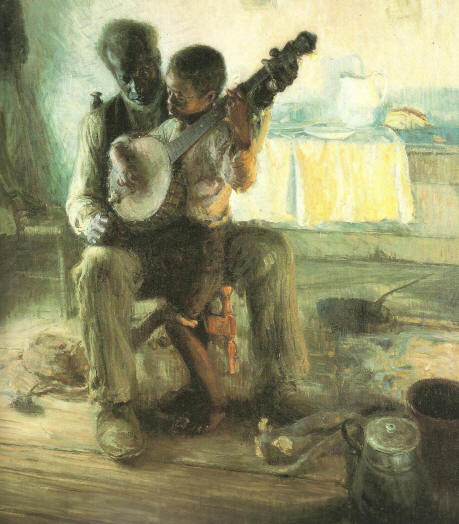

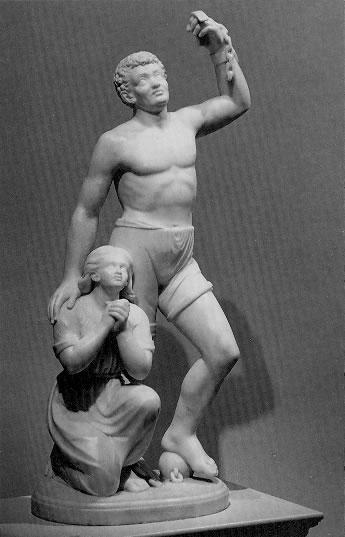

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s (1859-1937) painting The Banjo Lesson from 1893, for example, has been called a celebration of the oral traditions of black music making but also a nuanced achievement in color and tone experimentation. Celeste-Marie Bernier writes that the elderly man and young boy in a rustic cabin was about transcendence of their immediate material conditions. “Tanner’s use of light to illuminate his figures highlights the imaginative possibilities of art which can transcend the worn floorboards, scuffed boots and cracked walls of an impoverished southern cabin.” Likewise, the black and Indian sculptress Edmonia Lewis (c. 1843-c. 1911) made a marble sculpture in 1867 titled Forever Free that exemplified her tendency to represent African American subjects within a classical tradition of sculpture and with physical features resembling European standards. While this propensity has attracted distracters, surely her overall practice of making art as a black woman about black subjects and their quest for freedom must position her as a pioneer of African American artistic agency and resistance, and thus, cultural nationalism in the visual realm.

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s (1859-1937) painting The Banjo Lesson from 1893, for example, has been called a celebration of the oral traditions of black music making but also a nuanced achievement in color and tone experimentation. Celeste-Marie Bernier writes that the elderly man and young boy in a rustic cabin was about transcendence of their immediate material conditions. “Tanner’s use of light to illuminate his figures highlights the imaginative possibilities of art which can transcend the worn floorboards, scuffed boots and cracked walls of an impoverished southern cabin.” Likewise, the black and Indian sculptress Edmonia Lewis (c. 1843-c. 1911) made a marble sculpture in 1867 titled Forever Free that exemplified her tendency to represent African American subjects within a classical tradition of sculpture and with physical features resembling European standards. While this propensity has attracted distracters, surely her overall practice of making art as a black woman about black subjects and their quest for freedom must position her as a pioneer of African American artistic agency and resistance, and thus, cultural nationalism in the visual realm.

In music, cultural nationalism was also a complex affair as we can see through the brief discussion of the spiritual and two important nineteenth-century publications about black music below.

In music, cultural nationalism was also a complex affair as we can see through the brief discussion of the spiritual and two important nineteenth-century publications about black music below.

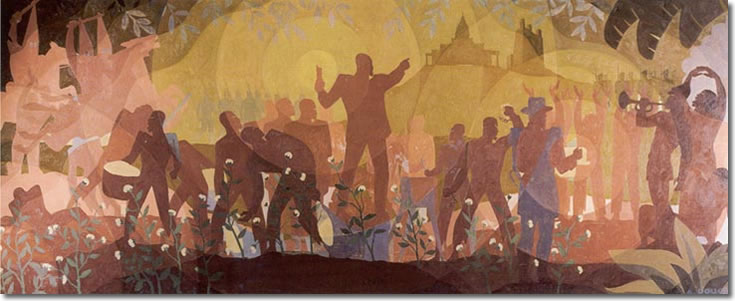

When the spiritual began to attract listeners from across racial lines, they became symbolic of an American sub-culture that exemplified the degree to which a “conversation of cultures” has defined the American musical landscape. It rose to prominence when The Fisk Jubilee Singers, a group of 11 men and women under the directorship of George L. White (a white instructor at the school), began performing art songs designed for the concert stage. Founded in 1866, six months after the end of the Civil War, Fisk University was established to educate newly freed slaves. White, being charged by the school’s administration to provide music instruction to promising students, provided lessons that included musicianship, classical repertory, and music from the own culture. With the melodies of the “folk” spirituals as an emotional focal point, these songs were arranged into strict part-singing and performed vocally in bel canto style. A new American genre was born. When White took the group on a tour in 1871 to raise funds for the struggling institution they performed a program similar to that of white singers but that also included spirituals.

Other black colleges would follow suit, using singing groups to raise funds, a tradition that has continued to the present. The Fisk Jubilee Singers and subsequent groups created a new framework for understanding black musical performance. The creation and popularity of the concert spiritual fit into the larger functions of commercialism, religion, and structural integration through education that has long defined African American culture. It also represented another example of the indigenization of culture seen in the initial “invention” of the spiritual in which Eurological poetic and song forms were transformed into a new genre through Afrological performance practice. In this latest turn, however, the Eurological ideas about the fully composed and bounded musical “work,” bel canto singing techniques, and concert decorum and praxis was applied to an African American body of song, producing a new form of indigenization that would become an important symbol of history, progress, and the idea of an expansive African American identity.

Other black colleges would follow suit, using singing groups to raise funds, a tradition that has continued to the present. The Fisk Jubilee Singers and subsequent groups created a new framework for understanding black musical performance. The creation and popularity of the concert spiritual fit into the larger functions of commercialism, religion, and structural integration through education that has long defined African American culture. It also represented another example of the indigenization of culture seen in the initial “invention” of the spiritual in which Eurological poetic and song forms were transformed into a new genre through Afrological performance practice. In this latest turn, however, the Eurological ideas about the fully composed and bounded musical “work,” bel canto singing techniques, and concert decorum and praxis was applied to an African American body of song, producing a new form of indigenization that would become an important symbol of history, progress, and the idea of an expansive African American identity.

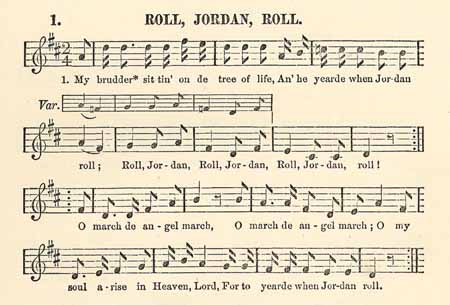

As awareness of black music continued its surge into the public sphere, it inspired numerous responses across the American culture industry. The anthology Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867, compiled 136 melodies with lyrics collected and edited by Northern abolitionists William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim. Transcribed from songs collected from various geographical locations in the South, the book was the first of its kind, designed to share with readers the mostly religious songs heard by the book’s authors. According to the editors, standard notation could not capture all of qualities of performance of these sacred and plantation songs. Represented in print as monophonic melodies, they in fact were performed as improvised heterophony. The compilers desired to capture slave culture’s “difference” in written form, an act that for them would at once save a sonic world for posterity and represent the nobility of an enslaved people in the contemporaneous moment. As Jon Cruz has written, the compiler’s “desire to transcribe black song making . . . reflected a tendency that extolled the virtues of a preferred and idealized notion of the culturally expressive and performing subject—in this case the spiritual-singing Negro.” For Cruz this activity showed how “black music making played a central role in the rise of modern modes of cultural interpretation” for future researchers. It laid the groundwork for an “interpretative turn toward the margins” of culture, an “ethnosympathy,” and an on-going search for cultural authenticity.

As awareness of black music continued its surge into the public sphere, it inspired numerous responses across the American culture industry. The anthology Slave Songs of the United States, published in 1867, compiled 136 melodies with lyrics collected and edited by Northern abolitionists William Francis Allen, Charles Pickard Ware, and Lucy McKim. Transcribed from songs collected from various geographical locations in the South, the book was the first of its kind, designed to share with readers the mostly religious songs heard by the book’s authors. According to the editors, standard notation could not capture all of qualities of performance of these sacred and plantation songs. Represented in print as monophonic melodies, they in fact were performed as improvised heterophony. The compilers desired to capture slave culture’s “difference” in written form, an act that for them would at once save a sonic world for posterity and represent the nobility of an enslaved people in the contemporaneous moment. As Jon Cruz has written, the compiler’s “desire to transcribe black song making . . . reflected a tendency that extolled the virtues of a preferred and idealized notion of the culturally expressive and performing subject—in this case the spiritual-singing Negro.” For Cruz this activity showed how “black music making played a central role in the rise of modern modes of cultural interpretation” for future researchers. It laid the groundwork for an “interpretative turn toward the margins” of culture, an “ethnosympathy,” and an on-going search for cultural authenticity.

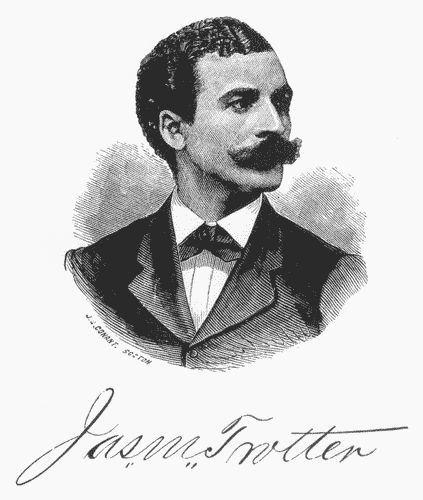

James Monroe Trotter’s Music and Some Highly Musical People, published in 1878 represented another approach to discipline black musical activity in the United States through literary means. Written by a black amateur musician and impresario, Trotter’s book, although focusing exclusively on 19th century African American musicians, is the first general survey of American music of any kind, making it a landmark in American music historiography. The book contains an appendix with the scores of compositions by black writers, the act of which intended to instill race pride, a sense of cultural nationalism, and “relations of mutual respect and good feeling” between the races. Because the book was written by a black citizen in the years following the Civil War and during the “Golden Age of Black Nationalism,” it resonates with the prominent racial and cultural politics of its day. A striking similarity exists, for example, between Trotter’s views and those of Alexander Crummell, the nineteenth-century pan-Africanist, founder of the Negro Academy, missionary, and statesman whose stated goal for the Academy constituted a “high-brow,” though staunchly pro-black stance: “to aid youths of genius in the attainment of the higher culture, at home and abroad.

James Monroe Trotter’s Music and Some Highly Musical People, published in 1878 represented another approach to discipline black musical activity in the United States through literary means. Written by a black amateur musician and impresario, Trotter’s book, although focusing exclusively on 19th century African American musicians, is the first general survey of American music of any kind, making it a landmark in American music historiography. The book contains an appendix with the scores of compositions by black writers, the act of which intended to instill race pride, a sense of cultural nationalism, and “relations of mutual respect and good feeling” between the races. Because the book was written by a black citizen in the years following the Civil War and during the “Golden Age of Black Nationalism,” it resonates with the prominent racial and cultural politics of its day. A striking similarity exists, for example, between Trotter’s views and those of Alexander Crummell, the nineteenth-century pan-Africanist, founder of the Negro Academy, missionary, and statesman whose stated goal for the Academy constituted a “high-brow,” though staunchly pro-black stance: “to aid youths of genius in the attainment of the higher culture, at home and abroad.

Trotter apparently believed black participation in Western art music to be a higher calling than vernacular music making and argued vehemently against the hindrance of “the art-capabilities of the colored race” because of “the hateful, terrible spirit of color-prejudice that foul spirit, the full measure of whose influence in crushing out the genius often born in children of [the black] race is difficult to estimate.” Trotter’s work is in some ways connected to that of Edmonia Lewis because it embodied a blend of black cultural nationalism based in Eurological aesthetic sensibilities.

Trotter apparently believed black participation in Western art music to be a higher calling than vernacular music making and argued vehemently against the hindrance of “the art-capabilities of the colored race” because of “the hateful, terrible spirit of color-prejudice that foul spirit, the full measure of whose influence in crushing out the genius often born in children of [the black] race is difficult to estimate.” Trotter’s work is in some ways connected to that of Edmonia Lewis because it embodied a blend of black cultural nationalism based in Eurological aesthetic sensibilities.

Clearly, the study of black expressive practices at this historical moment reveals how richly ideological and thoroughly complicated music, art, and literature could be as they both reflected and inspired the beautiful and terrible freedom now defining the age.

Tags: Charles Ware, Edmonia Lewis, Forever Free, Frederick Douglass, George White, Henry Tanner, James Monroe Trotter, James Sidbury, Luck McKim, Music and Some Highly Musical People, Phillis Wheatley, Robert Hayden, Slave Songs of the United States, Spirituals, The Banjo Lesson, The Fisk Jubilee Singers, William Francis Allen

Share On Facebook

Share On Facebook Tweet It

Tweet It